Filipino Terms of Endearment

/“Mano po,” a uniquely Filipino tradition and possibly a dying one as well.

Tiny irritants had niggled at me for years, prompting me to look deeper into kinship honorifics, or the courteous ways we address relatives.

When a “niece” of mine, Rebecca de la Cruz, passed away two months ago, I had to deal with this conondrum: Was she really a niece of mine (being the daughter of a first cousin)? Or was she actually “second cousin”? More confusion follows, of course, when one has to tackle the “once-removed” business.

While reconnecting with expat Filipino friends and strangers here in the US, I am addressed as kuya by younger Filipinos (which gives me a semi-thrill since I am the oldest of three brothers but we never used the kuya honorific at home). Then there are the terms manong and manang which at first sounds Ilocano, but actually isn’t. These terms evolved from the Spanish hermano and hermana; they now commonly refer to the older set of Filipino immigrants who came to the U.S. in the first half of the 20th century.

“In some large, traditional Filipino families, there is a hierarchic order and manner for how one addresses their older siblings.”

I will confess that I was very much a babe in the woods in the matter of Filipino honorific terms because even though I come from a “Tagalog” family, more explicitly, a Manila-based family, we hardly used these honorifics. We spoke more Spanish and English at home.

And yes, the whole matter may be regional (i.e., from a Tagalog-centric point of view), but even with non-Spanish-speaking cousins, Filipino honorifics for older siblings were not used when I was growing up. We, however, had close neighbors who faithfully used the sibling honorifics, from the oldest to the youngest. It all sounded very quaint to my ears, and I tucked it back in my mind’s Miscellaneous / Save For Later folder.

Now, 56 years later, it’s time to open that folder. Getting reacquainted with Filipino honorifics has turned out to be a learning experience for me.

As expressions of affection and inclusivity, everyone in the Philippines addresses older relations of some familiarity as tito or tita, which one source labels more a Manila affectation than anything else, having been spun from the original Spanish terms tio (uncle) and tia (aunt), There is also the tweaked distinction of tiyo and tiya being more properly reserved for blood-related uncles and aunts.

Similarly, in that catch-all manner, younger ones are all called “nephews” or “nieces,” even if, strictly speaking, they aren’t the children of your sibling but, say, the issues of a first cousin, in the extended sense. In the Philippines, the naming conventions work on first, the lateral levels, and then work their way down to the next generations.

The English/American system, on the surface, would seem to be simpler, easier and more direct. The children of your first cousin are your second cousins. Their children then become your third cousins, etc., etc. It works easily enough.

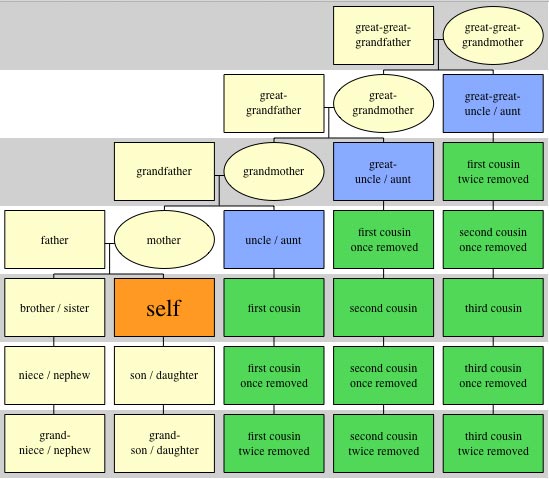

But to complicate things a little more, they have added this “once / twice / “thrice removed business. Adding the phrase “once removed” to your “first cousin, once removed,” means the offspring of your first cousin, or second cousins. The following chart attempts to shed some sense into the US/English matter of branding one’s relatives.

The Cousin Tree (Source: Wikicommons Media)

Sibling Terminology

In some large, traditional Filipino families, there is a hierarchic order and manner for how one addresses their older siblings. This actually comes from Chinese/Japanese sources.

For the boys, the first three oldest are usually addressed as kuya, diko and sangko; while the oldest three sisters are ate, ditse and sanse.

The oldest brother is kuya. It’s from the first Chinese ordinal, co. Remember when Charlie Chan referred to his sons as Son No. One and Son No. Two? Well, they indeed came into the world in that order. Present-day Chinese-Filipino surnames which start with “Co-“, like Cojuangco, Coseteng or Cua, for example, all denote having come from the oldest son.

The term for oldest sister, ate, comes from aitche (“ichi” meaning “first” in both Japanese and Hokkien, one of the Chinese dialects).

Diko, brother No. 2, and ditse, second sister, are rooted in “di” (or ni or ji, depending on your regional Chinese or Japanese bent). Just so long as it’s not “ditzy” as might be concocted by a mischievous first-born.

Child No. 3, sangko and sanse, come from the Japanese sansei, i.e, third in line.

In reverse order, the youngest one is lovingly called the bunsó, neutral-gender. To be gender-specific, totoy (the literal translation from Chinese is “the foolish one”), atoy, toto, itoy, doy are variant names given the youngest boy. The youngest girl was often called nene (literally, the “dull one” in Chinese.

A youngest girl cousin was nicknamed “Nene” (although she was Cecilia Jr., and our neighbors’ youngest son was nicknamed Atoy, which lined up very nicely with his given Christian name, Renato.) But my paternal grandparents, not coming from the Tagalog region, nicknamed their oldest son, Arturo, Jr., Totoy; while my youngest uncle, Enrique, was nicknamed Nene. There were no lasting effects from these seemingly “mis-gendered” nicknames.

One of the most beloved sets of siblings in popular world culture – ang mga batang von Trapp ng pelikulang The Sound of Music (1965). L-to-R: sina ate Liesl (Charmian Carr, R.I.P.), kuya Friedrich, ditse Louisa, diko Kurt, sanse Brigitta, Marta, and bunso Gretl, the nene of the group. Of course, those were the fictional names of the musical’s kids. (Source: Associated Press.)

In his notes on Filipino kinship terminology, L.J. Balajadia, cultural chair of the Pilipino-American Coalition, California State University, Long Beach, writes that ading (kapatid) is from Ilocano but has been adopted into normal usage since there is no direct translation to address younger siblings except the word kapatid. A reason for this is that kapatid is usually used to refer to only younger siblings, while ading can refer to younger siblings, relatives and friends.

“The words ate and kuya and ading aren’t meant just for siblings. They can also relate to the workplace and school. Using these words breaks the ice, as a means of showing respect due to a gap in age or superiority (a younger student asking an older student, or a mentee to a mentor). It shows the respect given to someone who is older, wiser, or more experienced. It’s like addressing professors and teachers by their honorific titles.

Other Relations – The Grandchildren

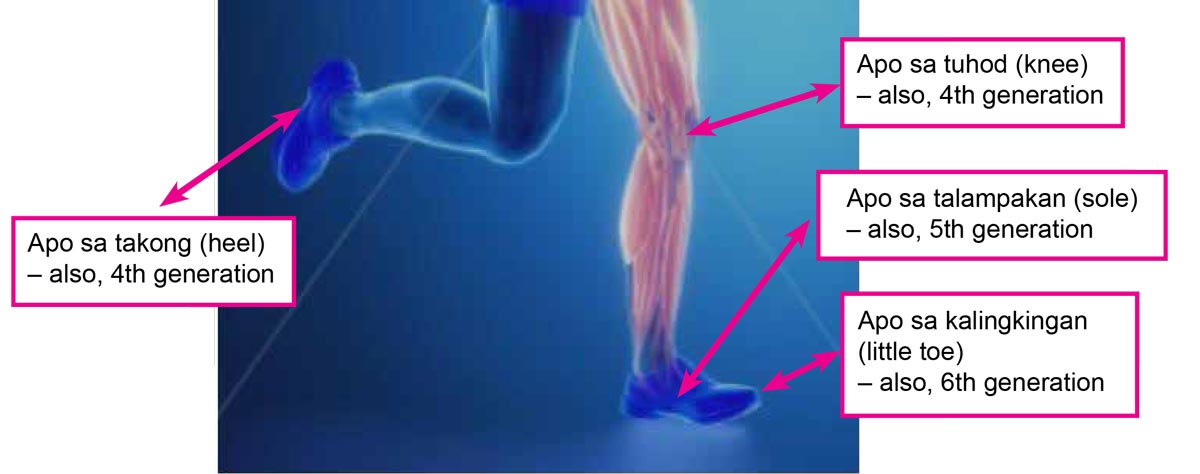

What is most fascinating is the quaint and colorful use of body parts to denote the varying degrees of grandparent-children kinship.

As one drills down the family tree, Filipino usage similarly goes down from the human leg—see illustration. To wit, the após — grandchildren. (But ápo, with accent on the first vowel, can also mean boss, patriarch, or older master.)

• “Apo sa tuhod (knee)” or sakong (or takong) (heel))” refer to great/grandchildren of the 4th generation;

•“. . . sa talampakan (sole of the foot)” refers to the 5th generation great-great-grandchildren;

•“. . . sa kalingkingan (little toe)” are the 6th generation tykes.

(Composite graphic created by author, ©Myles Garcia, 2016)

I could find no specific body-equivalent references online for the 1st, 2nd or 3rd degree grandchildren, but I seem to have heard apo sa siko (grandchildren of the elbow) previously, and which would make complete sense. Thank God, there are no apo sa lalamunan (throat), or apo sa balumbalunan (gizzard) or apo sa singit (groin). Aray (Ouch).

The In-Laws

Here are a few more arrows one can add to your quiver:

balae – collective, reflexive term when parents-in-law refer to each other

bayaw – brother-in-law

hipag – sister-in-law

biyenan – referring to one’s mother- or father-in-law

manugang – the reverse, when a parent-level refers to his/her son/daughter-in-law.

And we’ve probably known one or two in real-life: A bastard child or illegitimate issue, born out of wedlock, is simply anak sa labas (literally, the outside child).

Finally, surfing is catching on in the Philippines. But there are no words yet for “dude” or “dudettes” (not to be confused with “supporters” of a certain misguided president) so appropriate words will have to be found for those terms as well.

Until then, surf’s up, mga dewds!?!

References:

"Sibling Hierarchy," article by Penelope Flores, Filipinas Magazine, August 2000

“The Etymology and Usage of Ate/Kuya and Ading” by Hilario L. J. Balajadia, Cultural Chair, Pilipino-American Coalition, California State University, Long Beach

http://lbpac.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/4.-The-Etymology-and-Usage-of-Ate-Kuya.doc

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippine_kinship

http://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Philippines/sub5_6c/entry-3874.html

https://jonsquared.wordpress.com/2008/04/23/filipino-sibling-hierarchy/

https://www.rtcx.net/relatives-philippines-kinship-terms.html

Myles A. Garcia is a correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. He is also the author of two books: Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies, and most recently, Thirty Years Later... Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes. His first play, Dear Domenica, is undergoing developmental readings.

More articles from Myles A. Garcia