Filipino American Trailblazers

/Cecil Bonzo, Farmer’s Market Pioneer

By Elena Buensalido Mangahas

Cecil Bonzo, Sr. (Photo courtesy of Stockton FANHS)

In his teens he returns to America after the war and experiences the pioneer Filipinos’ way of life that author Carlos Bulosan immortalized in his book America Is in the Heart -- following the crops through seasons and to earn enough to sustain their immigrant life.

In 1955, Cecil Bonzo bought five acres of land in Lathrop, California and started farming, recalling the skills he learned as a young man and strove to be a successful farmer. Although he worked day jobs as an engineer surveyor, he tilled the land with the inspired by a childhood experience. He also recalled rural farmer’s markets where growers would sell their homegrown crops. Cecil desired the same set-up for his now high-yielding farm right in the heart of California.

Bonzo in Alaska in the 1950s (Photo courtesy of Stockton FANHS)

With backing from the Philadelphia-based American Friends Service Committee (which had supported Japanese American farmers who had to abandon their farms when they were sent to internment camps during World War II) Cecil was able to organize the Stockton Certified Farmer’s Market.

In time, he offered his land to newly arrived refugees from Southeast Asia who had come from farming communities in Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. He taught them how to lease land and create a livelihood that did not require mastery a new language. He empowered refugee families, despite language barriers and helped them understand America’s way.

As the naturally skilled refugee farmworkers generated high yields, Cecil grew the membership of the local farmer’s market and went on to start the San Francisco Heart of the City Farmer’s Market. The Rural Economic Alternative Program (REAP) was formed and funded by the Friends, and Cecil became the guru of many farmer’s markets in cities throughout California.

Farmer's markets are now everywhere, even just a few blocks off t the State Capitol in Sacramento in the summer, bringing together vegetable, fruit, flower and nut growers. Each market brings fond memories of Cecil Bonzo, the Filipino farm owner who spearheaded the local farmer's cooperative in Stockton, which eventually led to the creation of one of the best farmer's markets in America. The Hmongs of the valley remain the largest farming group, and their staple Asian vegetables are still sold as low as a dollar a pound. Cecil passed away in the spring of 1998, when the fields of his beloved valley were turning yellow with mustard, the first leafy vegetable of the season.

Elena Buensalido Mangahas, an Ilongga, resides in Stockton, California and engineers youth development programs for her paying day job and as her civic engagement. She is a founding board member for the Little Manila Rising! and a lifelong member of the Filipino American National Historical Society Stockton Chapter and works to preserve Fil-Am history.

More articles by Elena Buensalido Mangahas

Salvatore Baldomar, Filipino-Italian Seafarer

By Peter Jamero

Salvatore Baldomar (Source: peterjamero.net)

On Manila Alley were a Filipino barber shop, the Manila Karihan Restaurant, and Filipino VFW and American Legion clubs where cultural events were held. The neighborhood was first settled by Italian immigrants who welcomed Filipino seafarers who started coming in the early 1900s. With the scarcity of Filipina women, Filipino and Italian marriages, including Sal’s parents, soon became commonplace. (Marriages between Filipinos and whites in New York were legal.) He encountered little prejudice growing up, which he attributes to the mestizo/a make-up of his contemporaries, who were protected by the more established Italian neighborhood.

Sal’s bicultural family history is reflected in Sal’s memory: “On pasta Sundays my father would ask us kids at the table, ‘What do you like better, rice or pasta?’ To keep everyone happy, we poured the pasta sauce over the rice.”

As a teenager Sal made spending money as a runner for Keno games in Chinatown. At the same time he enjoyed New York’s rich cultural life. He remembered watching the first production of the Broadway hit “The King and I” where most the children’s roles were filled by kids of Filipino heritage. His own children were also influenced by the arts. His two sons are in the film industry, while his two daughters are in the visual arts.

Sal followed his father’s footsteps by marrying an Italian woman, Phyllis. He also followed his father’s footsteps as a seafarer, joining the merchant marines during the Korean War. Subsequently, he became co-owner of a meat market only to lose the business to a deteriorating neighborhood; and finally, after being burned out by riots in 1959.

These incidents eventually led to Sal and Phyllis moving to the San Pedro area in Southern California, with which he became familiar while he was in the merchant marines. I met Sal after hearing him ask a question at a Carson, California book signing in 2011, I immediately wanted to meet him. Why? I had never met a Pinoy with a New York accent!

From Peter Jamero’s blog: http://www.peterjamero.net/2019/06/29/peters-pinoy-patter-july-2019/

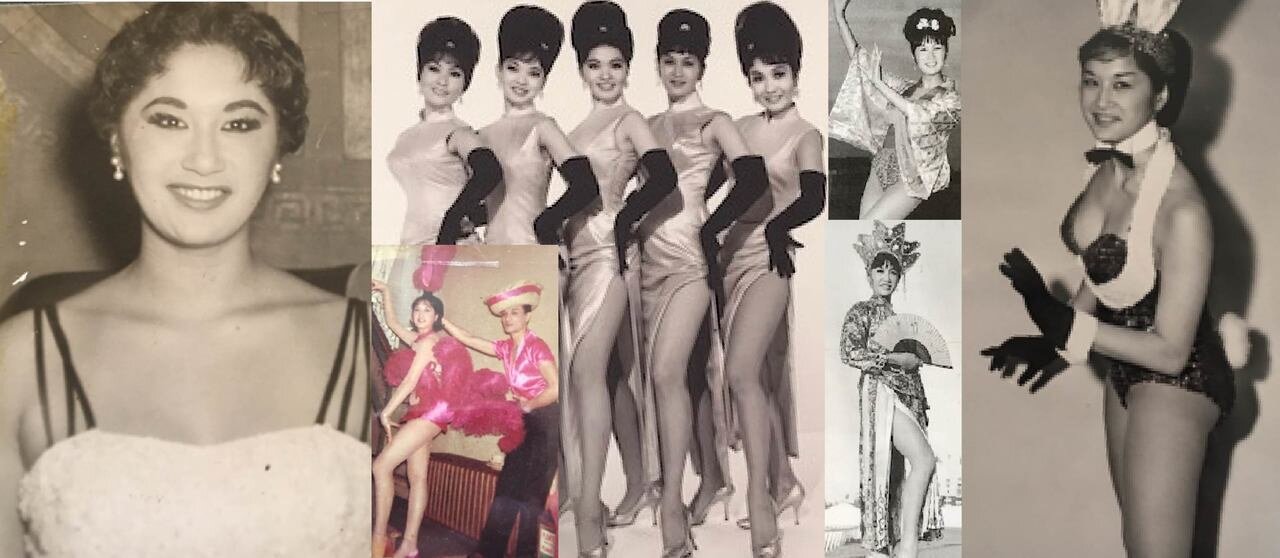

Arlene Lagrimas Dark, Forbidden City ‘Showgirl,’ Beautician

Arlene Lagrimas Dark (Source: peterjamero.net)

At 80 years of age, Arlene retains her slim figure and lives quietly in north Stockton. While dancing at Forbidden City was her chosen career, it was not the work she first sought. The youngest of six children, Arlene was born on August 31, 1938 in Stockton, California and grew up on Center Street in “Little Manila.” As a youth she played on a volleyball team that competed against other Filipina teams. In 1958 at the age of 18 she left Stockton for San Francisco to attend beauty school. But on the suggestion of her older brother, Tony Lagrimas, who was long-established as the lead male dancer at the nightclub, she became a showgirl instead ($55 a week was much more than she could make as a beautician).

Arlene Lagrimas Dark today (Source: facebook)

For more than a dozen years, Tony, 17 years older than Arlene, became her mentor, protector, and sometime dancing partner. Forbidden City was advertised as an all-Chinese show. So, the first thing Arlene had to agree to was change her stage name to “Arlene Wing,” the same last name Tony had assumed. She also was required to use makeup to look more slant-eyed.

Dancing came easy for Arlene who possessed the natural rhythm and grace of her Filipino background. In the book Forbidden City USA by Arthur Dong, “Oriental dancers” — Chinese, Japanese, Korean — were described as having “two left feet.”. Consequently, Filipino job seekers were favorably considered by the nightclub. Among the Pinay/Pinoy performers Arlene remembered were showgirls Anna Lea and Rita Adonis, singers Jimmy Borges and Pacita Todtod, and pianists Mike Montano, Flip Nunez, and Primo Kim.

By the 1960s Arlene’s pay had risen to $65 a week and then to an astronomical $200 a week when she went on tour with the Oriental Playgirl Review that traveled throughout the U.S., Canada, Europe, the Caribbean, and Japan. Performers were always paid in cash, never by check. Most showgirls were not from the San Francisco Bay Area. Steeped in traditional culture, local Asian parents considered it shameful for their scantily clad daughters to dance in nightclubs for all their relatives and friends to see. Arlene enjoyed being a dancer and being with the other showgirls. However, she strongly disagreed with the nightclub’s policy requiring showgirls to fraternize with guests during breaks (so they might spend more). Describing herself as a “rebel,” she led a protest that ultimately ended Forbidden City’s fraternization policy.

After the closure of Forbidden City in 1970, Arlene, in an ironic twist, purchased a beauty shop in Stockton that she still manages with the help of her daughter. Today, she continues to be close to Forbidden City friends. A surprised Arlene excitedly greeted several of her former showgirl pals who showed up unannounced during her July 14 presentation at the Filipino American Museum.

From Peter Jamero’s blog, peterjamero.net

Peter Jamero was born in Oakdale, California in 1930 and raised on a farm labor camp in nearby Livingston. He achieved “Filipino American Firsts” as Washington State Director for Vocational Rehabilitation; King County (Seattle) Department Director of Human Resources; Executive Director, Commission of Human Rights, City & County of San Francisco; Vice President for United Way of Seattle/King County; and Assistant Professor of Rehabilitation Medicine at the University of Washington.

He was founding vice president and long-time board member of the Filipino American National Historical Society. Author of Growing Up Brown: Memoirs of a Filipino American and The Filipino American Young Turks of Seattle, his most recent book Vanishing Filipino Americans: The Bridge Generation was published in 2011. Retired, he lives in Atwater, California.

More articles from Peter Jamero