Fact-Checking the History of San Francisco’s Manilatown

/The earnest video journalist recounts how 30,000 Filipinos – confronting racism and violence – created a thriving neighborhood within ten blocks of Kearny Street. This widely viewed video describes a San Francisco that was “racially segregated by design.”

Community historians interviewed on the video detail the violence that Filipinos in San Francisco endured; how they could not even venture beyond the ten block boundaries because they “could get beat up, even killed.” More chilling is that of “white vigilante groups that would hunt them down, try to take them out of town, murder them.” The narrator explains that such violence “forced Filipino men to stay within the boundaries of Manilatown.” The narrator emphasizes that beyond Broadway Street, “Filipinos were denied apartments.”

This powerful and moving story, however, misrepresents the story of Kearny Street. And in an age of misinformation, Filipino Americans need to be vigilant in spotting unreliable and confusing reportage.

“Perpetuating an inaccurate history of Kearny Street/Manilatown serves to flatten the founding Filipino immigrants in San Francisco into a mass of terrified victims too afraid to leave the safety of their neighborhood. ”

The Myth of 30,000 Filipinos

How many Filipinos lived in Manilatown in the early decades of the 20th century? The estimated number had changed over the years. In an undated essay, a community historian noted that San Francisco’s Manilatown “existed from the 1920s to the 1950s and was home to a few hundred Filipinos.” In the mid-1980s, the same historian estimated “At its height, over 1,000 residents lived in Manilatown.” By the late 1990s, that number had grown to 10,000. Thirty thousand Filipinos started being mentioned in the last 15 years. However, not one of these estimates referred to its sources.

Coincidentally, the U.S. Census counted some 30,470 Filipinos living in California in 1930; this number increased to 31,400 by 1940. The slow growth between those years can be attributed to the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1935, which curtailed Filipino immigration to the U.S. mainland to an annual quota of 50. A repatriation program in the late 1930s also sent almost 2,200 Filipinos back to the Philippines.

By the 1940 Census, the number of Filipinos in San Francisco was around 3,480. Their numbers would grow as immigration picked up after the World War II, especially after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was passed. The Filipino population in San Francisco peaked in 1990 at about 42,650.

Except for the International and the St. Paul hotels, most single-room occupancy hotels (SROs) along Kearny Street and the side alleys were small narrow buildings with two- to three-storeys of rooms above commercial businesses. Altogether, these residential hotels could not have housed more than 2,000 residents at any one point; most did not cater to just Filipinos.

Boundaries of Manilatown

Community and academic scholars provided differing boundaries as well, including “a three-block radius around Kearny Street and Jackson,” “Kearny Street from Pine to Pacific” (six blocks), and the video’s ten blocks from “Market Street to Pacific.” Such differences are understandable as neighborhoods and communities expand and contract over time. The number of Filipino businesses on Kearny, for example, increased as the San Francisco population of Filipinos grew.

But it is unlikely that Manilatown at one time stretched for ten blocks. City directories from the 1900s to the 1950s listed mostly offices and retail establishments lining the blocks from Market to Bush. Fire insurance maps from that period confirm such land uses. It is very unlikely that Filipinos owned or operated businesses or lived in those blocks of Kearny Street.

A 1940 guidebook of San Francisco’s ethnic neighborhoods described the boundaries of the Filipino enclave on Kearny Street as the four blocks between “Pacific and Sacramento where their hotels and shops, cafes and restaurants.” The guidebook also noted that San Francisco’s Filipinos called the Kearny Street neighborhood the “Escolta,” a reference to the commercial street in Binondo, Manila’s own Chinatown district. Kearny Street was not dubbed “Manilatown” until the late 1960s.

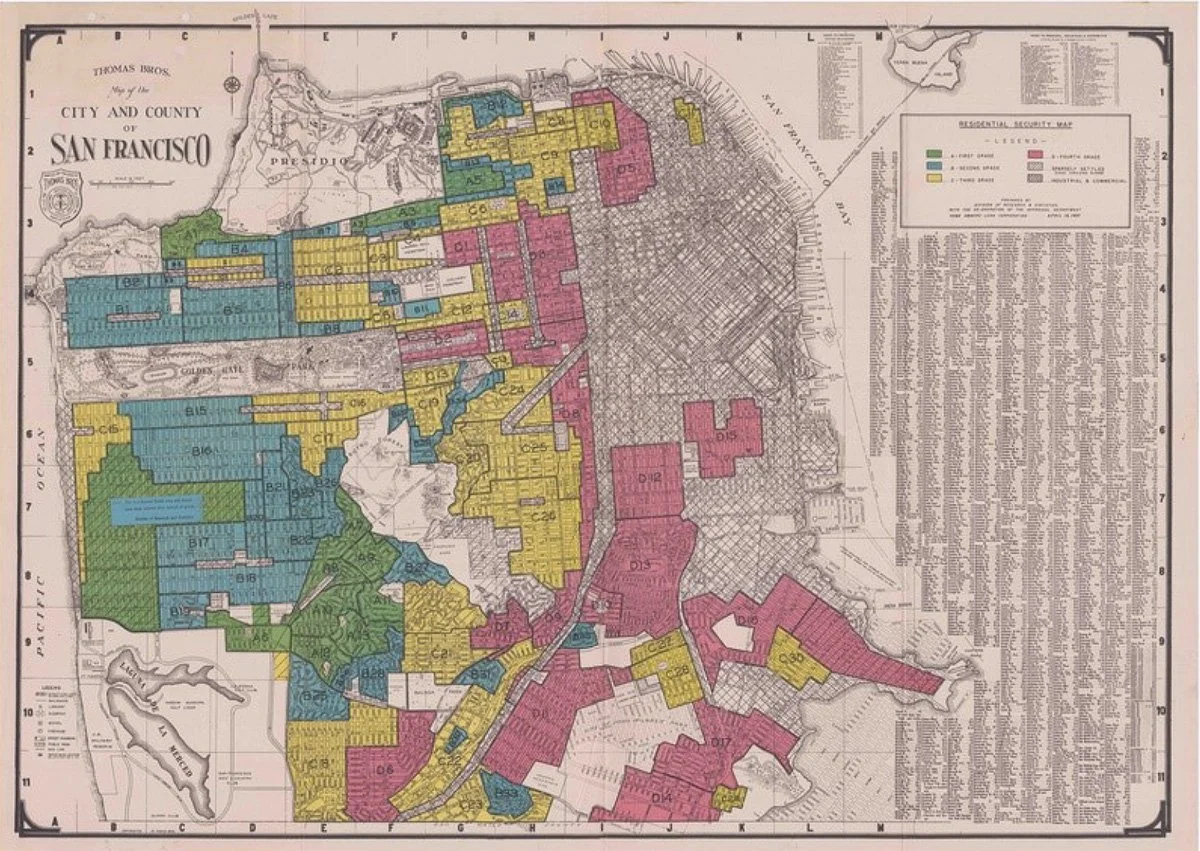

The Redlining Map

As evidence that San Francisco was “racist by design,” a redlining map is briefly shown on the video (see Map 1) This appears to be a disingenuous ploy, as the narrator does not explain what the different colors meant.

Map 1: Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) Map of San Francisco, 1937. HOLC maps show mostly working class and integrated neighborhoods as red or yellow areas (“hazardous” and “declining” neighborhoods). Commercial and industrial neighborhoods are hashed, with no color assigned.

The colors represent grades assigned to residential neighborhoods for home mortgage lending risks. Kearny Street was and still is in a neighborhood of mostly commercial and mixed uses – hence, it was in an area that had hashed lines and was not assigned a color code on the map. Without an explanation of the map’s color coding, however, a viewer might conclude that because Manilatown was shown outside the colored areas, Filipinos were shut out of much of San Francisco.

Redlining maps were created beginning in the 1930s and were used for assessing risks for federal home loans. The red indicated neighborhoods with “hazardous” lending risk, hence the term “redlining.” Yellow neighborhoods were “declining,” the blue areas were rated “good,” and green areas had the “best or lowest risks” for federal home loans.

Mapping where Filipinos lived in San Francisco based on census records placed them mostly in the red and yellow neighborhoods (see Map 2). San Francisco did not have that many green and blue areas as there were few neighborhoods that had covenants prohibiting nonwhite residents. Filipinos in such neighborhoods were likely employed as live-in domestic workers.

Map 2: Map detail showing where Filipinos lived in Chinatown as well as parts of the North Beach and Tenderloin/Nob Hill neighborhoods. The beige blocks represent the boundaries of Chinatown in 1940. Kearny Street was its eastern edge, where pioneering Filipinos ran restaurants, pool halls, barbershops, cigar stores, and an employment center. Filipinos who settled in San Francisco and their transient countrymen – farmworkers and seafarers – considered Kearny Street as the community’s commercial heart. The mostly small residential hotels along the street and connecting alleys meant that no more than a few hundred Filipinos lived on Kearny Street at any one time.

Vigilante Groups?

Although many Filipinos in San Francisco were undoubtedly harassed or have suffered indignities especially during those early decades, there is no evidence of vigilante groups that hunted them down and kept them within the confines of 10 blocks of Kearny Street.

The video image of the first news cutting briefly that is flashed across the screen was cropped and does not show a date or indicate where Filipinos terrorized by the mob fled; the second cutting just shows a jarring title and nothing else. The articles are likely referring to the riots in the Watsonville/Salinas area in the fall of 1929. Reports of the 1929 and 1930 riots in the valley 90 miles away would have understandably caused alarm to Filipinos in San Francisco. But it is unlikely to have caused them to keep to the boundaries of Manilatown as asserted by the video’s narrator.

The Importance of Getting the Story Right

Kearny Street played an important function in the nascent Filipino American community. It served as a commercial center with Filipino restaurants and cafes, barbershops, cigar stores, and pool halls. And those businesses served as gathering spots for newcomers and those just passing through. Kearny Street also served as marshalling area when Filipinos held or joined civic parades.

The Census enumeration records for Filipinos living along Kearny Street and in Chinatown was around 350 in 1930 and 330 in 1940 (see Map 3). The numbers of those living in SROs had decreased over the decades as Filipinos put down roots in San Francisco. By the 1940s, most Filipinos in San Francisco were living in multifamily duplexes and triplexes, in apartment buildings; more than a handful lived in single-family homes they owned.

Map 3: Location of Filipinos in San Francisco, 1940. An overlay of the HOLC map shows that most Filipinos lived in red and yellow neighborhoods, as well as in commercial and industrial neighborhoods. Filipinos in the blue and green areas were likely employed as live-in domestics.

It is not necessary to inflate the size of its population or enlarge its boundaries. Implying the terror and violence inflicted on Filipinos elsewhere as transpiring in San Francisco does not make sense.

Moreover, perpetuating an inaccurate history of Kearny Street/Manilatown serves to flatten the founding Filipino immigrants in San Francisco into a mass of terrified victims too afraid to leave the safety of their neighborhood. It ignores the majority who settled in the City’s various working-class neighborhoods, raised families, adapted, and integrated into a complex American society that was not what they were taught it to be.

Racism is complex and Filipinos of that time dealt with its humiliations the best they could. They sought housing where they were welcomed and could thrive. They went to meetings, held socials and balls, and worshiped at their churches. They had sports clubs, and their tennis teams made the sporting news. They may have built their communities and social institutions in the larger Western Addition district, but Kearny Street remained the commercial heart for San Francisco’s Filipinos through the 1950s.

The history of the International Hotel struggle for affordable housing needs to be told. But continuing with a myth of improbable population size in an imagined neighborhood size of Manilatown – especially if it can be fact-checked – is a great disservice to the community and the future generations. Over 1.6 million people have already watched the video that misrepresented the community and were likely affected by such distortion.

This is unfortunate for many of them will not know the rich history of Filipinos in San Francisco. That it was an engaged community that knew how to express its concerns and fight for their rights. There are stories like that of Celestino Alfafara, who filed the legal test case that won Filipinos the right to own land in California. http://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/celestinos-crusades

It was a community with few women, but who nevertheless made their voices heard. Like Pilar Guerrero who spoke before the San Francisco Board of Supervisors decrying the discrimination her family endured as they searched for housing in the City. Or Estella Sulit, a Filipina lawyer who made rounds of Bay Area women’s clubs speaking on topical issues like Philippine independence and the Pacific war. There were Filipinas who were part of the labor force, like Lourdes Bollozo, who was head nurse of Ward C of UCSF Hospital in the 1930s.

By 1940, it was a community with a second generation born and raised as San Franciscans. Like Olympian gold medalist Victoria Manalo Draves, who grew up in South of Market where a park now bears her name. Or Carlos Villa, a renowned visual artist who was born in the Tenderloin a few blocks from the Asian Art Museum, which recently held a retrospective of his work. Award-wining rhythm and blues singer Sugar Pie deSanto, was born in New York but raised in the Western Addition.

Such stories are plentiful and need to be explored, shared, and not forgotten. Filipino Americans deserve a fuller history.

San Francisco-based M.T. Ojeda is a recently retired urban planner and is now indulging a passion for history and geography.

More articles from M.T. Ojeda