F. Sionil Jose and a Nation’s Memories

/National Artist F. Sioniol Jose

"All art is propaganda, but not all propaganda is art," he says. For extolling the heart and soul of the Filipino people through storytelling, Sionil Jose is hailed as a National Artist. His numerous awards include the Outstanding Fulbrighters Award for Literature, the Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Arts et Lettres in France, and the Pablo Neruda Centennial Award in Chile. His works have been translated into 28 languages, including Japanese, Korean, Russian, Latvian, Ukrainian, English, and Dutch.

A discerning politico, Sionil Jose has known every postwar Philippine president, some quite intimately. He regards Ramon Magsaysay as the nation's greatest leader and Ferdinand Marcos as "the worst, even morally." Meanwhile, Fidel Ramos is "a very good friend."

At 95, the writer has truly lived a fabled life. The irony is that he had never intended to be a writer: "I wanted to be a doctor, but I flunked biochemistry in college." Being editor of the University of Santo Tomas paper along with freelancing gigs for The Saturday Evening News and Manila Times, two of the most widely circulated newspapers of the 1940s, steered Sionil Jose towards creative writing. At last, he could express a love of stories that began in childhood. He learned his craft from tales his elders narrated of provincial life in his native Pangasinan as well as from the greats of western literature by the time he was ten. His fifth-grade teacher, seeing her pupil's love of books, introduced him to Don Quixote by Miguel Cervantes and Willa Cather's pioneer classic, My Antonía. "I started writing when I first had memory," says Sionil Jose, "because memory is a writer's foremost equipment." Indeed, Pangasinan is the setting for a number of his works of fiction.

However, it was Jose Rizal's call for emancipation from Spanish colonialism in Noli Me Tangere, which Sionil Jose also read at the precocious age of ten, that affected him the most. "His politics, his use of literature as social instrument and, most of all, his love of country," was Rizal's hold on him, he says. Later, as an adult, he discovered the essays of Salvador Lopez and the stories of Jose Garcia Villa, men of letters who imbued their works with substance and artistry. When, at the age of 25 in 1949, Sionil Jose embarked on his writing career, he was faced with this dilemma: "Filipinos don't read [novels]." He used his influence as a journalist to disseminate his prose, submitting works for publication in serial form to magazines such as the weekly Woman's and the Sunday supplement to Manila Times, which he himself edited. His reputation flourished and his readership grew such that, in 1955, he had the opportunity to reach an American audience.

A desire to be published in the United States had been growing in him. Jose Garcia Villa and Carlos Bulosan had already earned American recognition. Malcolm Cowley, the prominent editor at Viking Books, invited Sionil Jose to Connecticut, where he connected the author with a literary agent. The novel of interest was Tree, which explores class inequality from the perspective of a young boy and is set in Sionil Jose's hometown of Rosales. The three of them discussed changes to the text needed for the comprehension of American readers; but the project would never materialize. Back in Manila, in the midst of revising, Sionil Jose had a realization: "I asked myself for whom am I writing, which is perhaps the very crucial question. Am I writing for the Americans? Of course not. I am writing for myself and for the Filipinos."

F. Sionil Jose’s “Tree”

Despite pleas from both his agent and Cowley, he stood his ground. Only some 30 years later did he finally have his American debut, when a Harvard scholar discovered his works during a trip to the Philippines and brought them to the attention of a close friend, who happened to be an editor at Double Day.

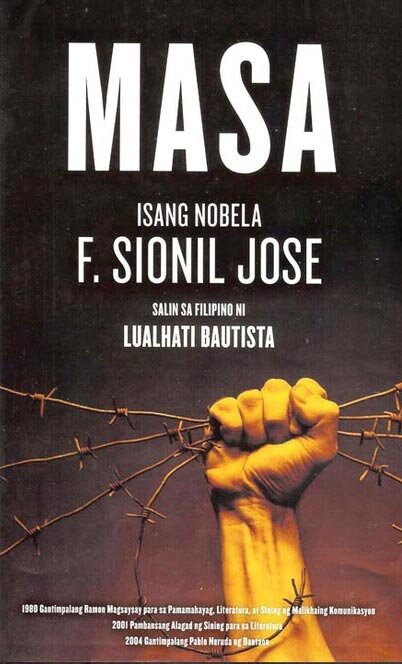

Sionil Jose sums up his devotion to the Philippines: "History enables one to remember, and Filipinos don't have a sense of history." Hence, his mission to preserve in words bygone moments of the national experience that are becoming ever fainter in the collective memory. Nonetheless, Sionil Jose has an unyielding faith in the country's future. He reveals that he had originally envisioned the Rosales Saga as a series of four books, with a bleak conclusion that consists of a suicide. The idea for another sequel started to brew upon reports of rebels against martial law sacrificing their lives to the cause of freedom. Their deaths evoked the patriotic spirit that had defeated Spanish colonization a century earlier and gave Sionil Jose hope for the Philippines. Mass, the fifth and final installment of the saga, ends with a rebirth.

F. Sionil Jose’s “Mass” (Masa)

For F. Sionil Jose, to write about Filipinos is to write with a veracity that honors their heritage. He is still hoping for a Philippine literary renaissance: "Forget American literature because the greatest cultural influence in this country today is American, and it's very stifling."

Rafaelito V. Sy is the author of Potato Queen, a novel about the relationship between Caucasians and Asians in the San Francisco gay community of the 1990s. Please visit his blog of short stories and inspirational essays on film: www.rafsy.com.

More articles from Rafaelito Sy