Discovering a Long-Lost 19th Century Filipino Master Painter

/I was reading Provenance, a book by Laney Salisbury and Aly Sujo, an exposé of art forgery and art scams in the UK in the 1990s, when mention of a particular appraisal caught my attention. Peter Nahum was appraising an objet d’art on an episode of “Antiques Roadshow UK,” and this line jumped out at me: “When a banker brought in a collection of twenty-five Filipino watercolors he’d inherited from his grandfather, Nahum knew right away that it was gold, worth £240,000, as it turned out” (page 130).

I was immediately intrigued. A whole torrent of questions rushed at me: Who had painted those very valuable watercolors? Who was this “Jose Honorato Lozano”? What was a rare and exceptional album of his doing in Europe? How come I had never heard of this artist? How could I see this episode for myself? What became of that rather rare volume?

Strangely enough, a few days later, on Facebook, a friend, J. Ramon Faustmann, originally of Bilbao, Spain, who became a practicing architect by way of Manila, posted some wondrous watercolor scenes of life in Manila, 1847. Could these have been by the one and the same unknown artist who was on the verge of my discovery?

Then another Facebook acquaintance, Isabel Aspillera, chimed in and confirmed that indeed these watercolor scenes were from an 1870 album of scenes by the master watercolorist whom I was now learning about. Furthermore, she remembered that particular episode of “Antiques Roadshow-UK” in question.

Aha! We were getting somewhere. So, with those scant clues, I dug into Antiques Roadshow-UK’s archives as much as I could. I came up empty-handed.

International TV debut via the BBC

And then, just as mysteriously, within 48 hours, there appeared the link for that crucial “Antiques Roadshow UK” episode from 1995. I don’t recall now on which medium the link first appeared to me, but here it is:

In it, appraiser Nahum evaluates “Album de Manille et ses environs,” an album of twenty-five watercolors by Filipino artist Jose Honorato Lozano (c.1821 - c. 1885) depicting scenes in and around Manila of the 19th century.

A British art show? A Belgian banker? Filipino watercolors from the 19th century, in mint condition? How did these all tie in? (More about that Nyssens-Flebus book later.)

Scant Lozano Biographical Facts

My early research on Lozano showed little information. He was born in 1821, the son of a lighthouse keeper at Manila Bay. He reportedly grew up in the Sampaloc area. Jose’s education is not known, and after many of his works were recently assessed by experts, they gleaned that he was either self-taught in artistic style; or his technique was heavily influenced by Chinese art teachers who were fluent in the calligraphic art of Chinese scrolls.

Lozano did get some mention in historic accounts of the period, specifically from chronicler Rafael Diaz Arenas who, as early as 1850, wrote that Lozano “. . . was a watercolorist without rival.” He also painted in the conventional costumbrista tradition as a means of supplying the demand for graphic souvenirs of Manila to foreign visitors (mostly American sea and land merchants).

For those also new to Lozano, you will discover that he is a visual chronicler par excellence of the ways, mores, rituals, landmark buildings, costumes and customs of both the powerful and the average people of mid-19th century Hispanic Philippines. Here is a small sampling of the ethnographic art Lozano excelled in:

Rendering of Philippine fauna (Plate #73) from the Gervasio Gironella album.

In a way, Lozano was like the James Audubon of Hispanic Philippines (or can Audubon be called the Lozano of the USA?), in that both prolific artists and recorders of their specific genres rendered their impressions in watercolor.

Lozano married one Maria C. Castro, a seamstress by trade; however, from the artist’s works, scholars have surmised that the couple was probably childless. Moreover, based on what has survived and surfaced of his work to this day, one can safely assume that Lozano must’ve enjoyed a fairly full and lucrative career. He attracted a well-connected clientele that obviously recommended him for even more works, and there appeared to be no shortage of commissions.

The circumstances of Lozano’s demise, however, are even far sketchier. How, where, under what conditions did he pass away? Did he die penurious, after a long and protracted illness maybe? Where was he buried? Considering that he most probably enjoyed an enviable reputation already within Manila’s art circles, and this was towards the final decade of Spanish rule in the Philippines, the only thing that can be ascertained is that Lozano died in 1885, age 64. The artist, however, left behind a magnificent legacy, which has just been re-pieced together in the last two decades.

Lozano is also the best-known exponent of the subgenre of graphic fine arts known as Letras y Figuras, an ethnographic style in which the letters (of a patron's name) are composed primarily of contoured arrangements of human figures and vignettes of scenes in Manila. This niche style can trace its origins to the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages. Following is the best example of Lozano’s Letras y Figuras work for one Diego Viña y Balbin, watercolor on paper, ca. 1850.

The above piece belongs to the United Laboratories collection, Manila.

Watercolor vs. Oil

Watercolor (or gouache) painting is always considered lightweight, even bush-league, compared with oil or tempera-painting for frescoes and murals. Of course, watercolor-gouache is cheaper for artists who cannot afford oil paints. Second, given similar conditions the art pieces may be exposed to, watercolors will fade and deteriorate faster than oils. Third, with water color you cannot get the same richness, burnished shades that rich patrons—especially in the Renaissance and Middle Ages with their resplendent costumes and uniforms—like to see themselves rendered in. Imagine an Ingres countess vs. an Audubon bird—fine, iridescent silk vs. rough but equally beautiful plumage. Hence, watercolors were reserved for flora, fauna, landscape scenes – subjects who could not pay artists’ fees which human subjects of oil portraits could. Thus, watercolor artists are considered minnows compared with the whales of visual fine arts – the Van Goghs, the Renoirs, the Gauguins.

But Lozano though was more than just a visual chronicler of the times and mores of his era. Unfortunately, there is no known photograph or likeness of Lozano extant, and he may have been a very modest man. He must also have been playful because the following plate below is the only known, acknowledged self-portrait; but only their barely recognizable profiles are shown. They are encircled for the reader’s ease as they would be nearly impossible to find without the guides.

Retrato del Pintor Lozano y su Espoza. (sic), Portrait of Painter Lozano and his Wife). Their profiles in center, encircled in red: Lozano, left; his wife, Maria, right. (From the Ayala Album)

Serendipitous Streak Continues

About a month ago, I was contacted by a Murvyn Callo, again, on Facebook. He turned out to be a long-lost relation, and by sheer chance was into a lot of artistic heritage stuff of both our paternal roots of Zambales and of Filipiniana.

Callo’s reaching out to me proved once again to be auspicious in more ways than one: first is that I was also finishing a one-act play, which had early aviation as its theme. Turns out there is something in cousin Callo’s resume that was connected with aviation—but that’s for another day.

Second was that Callo, although living in Southern California, has a copy of the current best reference source on Lozano, called “José Honorato Lozano - Filipinas 1847” by Jose Maria A. Cariño close by that I could borrow. The book, printed in 2002 and weighs nearly 3 lbs., is currently out of print. So, it was a godsend that Callo’s copy, happened to be with his sibling living in the SF Bay Area. Sweet.

So, with the elusive Lozano “bible” in hand, the mystery of this “little-known” watercolor artist of 19th century Filipinas was finally solved, filling that crevice of ignorance in my knowledge of art history.

Most of Lozano’s re-discovered watercolors are found in bound volumes. There are at least five complete folios known:

1. Ayala Album

2. Nyssens-Flebus 1847 Album

3. Gervasio Gironella Album

4. Jose de la Gandara Album

5. ML Album

Because the above are in private hands or affords only limited access, I have decided to share a few of the works, but only a few due to space reasons.

The Ayala Album

The first considerably comprehensive volume of Lozano’s watercolors came to light in 1992. A collection of 18th and 19th century books on the Philippines, including one Lozano album, became available as a package. They belonged to the owner’s ancestors who did business in Hispanic Philippines but returned to Spain in 1898. The internet was in its infancy in 1992, and because auction-fever had not yet hit collectors and “repatriation” winds were just blowing, the collection was first offered privately to the Ayala Museum. Flush with funds and exercising their own Iberian-peninsula connections, the Ayalas jumped at the chance to acquire the rare collection and bought it for their museum in Makati.

The “Ayala Album” contains 60 works by Lozano plus a few more by two of his contemporaries. It is the only extant Lozano folio wherein the artist signed and dated his works, e.g., “por José Lozano en 1851”. Thus, even though there are a few other works by others, scholars have been able to glean significant aspects of Lozano’s life by the mere fact of his identifying the works with dates vs. total blanks in his other commissioned albums.

The Nyssens-Flebus Album

Then there is the Nyssens-Flebus Album, the root cause of the Lozano Revival Fever. In the video clip, shot in Belgium when the show made a visit to Brussels, the volume’s owner was a Jean Flebus, a banker. Flebus claimed that he inherited it from his great-grandfather, one Gérard Théodore Emile Nyssens (1815-1906), a tobacco merchant who conducted business with Manila in the 19th century.

Nyssens was reported to have first visited Manila in 1844 and, as the story goes, commissioned Lozano to paint a whole series of life in Manila at the time. He then brought the 25 individual plates back to Europe and had them bound there into one volume. It stayed in his family over the years, even surviving the two world wars. Thank God, Hitler, Goering and the whole marauding Nazi gang did not loot or destroy much of Belgium

Appraiser Nahum, unaware of Lozano at all, was supremely impressed enough by the folio that he gave it a very conservative estimate of £100,000. In three short months, on July 14, 1995 (Bastille Day in France), the Nyssens-Flebus Album (as it came to be known) went to auction at Christie’s London. It fetched £265,500 (almost US$419,000 at 1995 exchange rates), a world record then for an unknown watercolor painter and one with no sales history on the international art marketplace. That £265,500 price could very well have been an auction record for a relatively unknown Filipino artist as well.

Below is Pilgrimage to the Feast at Antipolo plate from the Nyssens-Flebus Album.

Mestizas in promenade attire

View near the town of Taguig on the Pasig River.

In 2002, Christie’s published reproductions of the plates from the Nyssens-Flebus Album in postcard format. Because it paid for the publication, the auction house somehow managed to put a copyright imprint on those; but that move remains questionable since these works were created in the mid-1800s, in another part of the world and long before there were any copyright laws to speak of.

“Auspicious” Fallout from the Break-up of Some Lozano Albums

The rediscovery of Lozano’s art due to its international TV exposure and the buzz it created among Filipino art enthusiasts also opened up two new unintended “vistas.” It brought to light a lot of other 19th century Filipino artists not quite in the same firmament as Luna and Hidalgo but worthy of attention just the same. It turns out there’s a whole school of them (C. Laforteza, Miguel Añonuevo, Hilarion Eloriaga Asuncion, Francisco Bautista, Jose Lerma, to name some) who imitated Lozano’s Letras y Artes style.

And because of the internet, more pieces by Lozano and his contemporaries have appeared on the scene. Old collections in Spain, other European libraries, and lesser known sources in the Philippines are flushing out their archives, putting some of their holdings up for sale, enabling more art aficionados, not just the usual well-heeled suspects, to have a shot at acquiring one or two pieces.

Just last week, I made one such connection with a budding “light” Filipiniana collector from the Los Angeles area. Again, the Serendipity gods must have still been with me. This LA-based collector, originally from Negros, purchased his Lozano’s via online auctions from Spain, pieces which probably came from broken up Lozano albums previously unaccounted for. (This collector and I promised to meet in person in late October when I travel down to southern California for a Fil-Am author event at the Philippine Expressions bookstore in San Pedro, CA, on October 26, 2019. More details on that event to follow.)

The Gervasio Gironella Album

The most complete, intact and comprehensive Lozano folio is the Gervasio Gironella Album. This album belongs to the Bibleoteca Nacional de Madrid (the National Library of Madrid). Its full title is “Album – Vistas de las Islas Filipinas y Traces de Sus Abitantes (sic) – 1847” (Album – Views of the Philippine Islands and Records of Its Inhabitants – 1847); or the Gironella Album in short. It contains up to 80 plates and because it has been kept in protected, ideal conditions the last 150 years, it is the best preserved of all the known albums.

It was probably commissioned for or by Gervasio Gironella, the Superintendente y Intendente del Ejercito y de la Hacienda (Superintendent of the Army and Quarter Master General of the Treasury) during the last decades of Spanish rule in Manila, which made him the second most important official in the Philippines at the time.

How did the Gironella Album begin its voyage of re-discovery? In January 2000, Madrid was hosting a conference on antiquities conservation, with delegations from the ex-colonies of Spain attending. The Fine Arts section of the Bibleoteca Nacional decided to open up its archives and share something special with the various foreign delegates from their respective countries. The Philippine representative, Regalado “Ricky” Trota Jose, Jr., was shown the Gironella Album – which apparently had not been seen by any Filipino eyes in the intervening 20th century.

With the buzz from the Nyssens-Flebus album, the repatriation of the Ayala album, excitement among Filipino Lozano scholars was simultaneously building that it was time to do a new reference (not quite a catalogue raisonne) on the artist. José Maria A. Cariño, who happened to be assigned to the Philippine Embassy in Madrid at the time and was going to be the lead author of the planned volume, then became perfectly placed to spearhead the ambitious project. The officials at the Bibleoteca Nacional who had, in fact, opened a Pandora’s box in showing the long dormant volume, became equally enthusiastic about the project. They extended every cooperation they could to the Cariño team, going so far as to loan the 176 transparencies the Library already had from the plates of the book. That alone would probably have accounted for 3/5ths of the production costs of the book.

Thus, we are privileged to share seven of the plates from the Gironella Album (and then the Cariño book) with the reader. Thanks must also go to J. Ramon Faustmann from whom I saw my first Lozano images and for creating a digital file of some of the plates. (Of course, these are paintings that Lozano would have put together over a period of perhaps, at least three years, in the late 1840s – 50s.)

Plate #2 –Desembocadura del rio Pasig en la Bahia (Where the Pasig River Opens up into Manila Bay) A busy day in the port of Manila; Fort Santiago, left. Lighthouse, center, in the distance (where Lozano’s father might have worked).

Period photograph by John T. Pilot, ca 1900-02, of the lighthouse in the center of plate above. It is the oldest light station in the Philippines but it looks different today. It is located at the north jetty of where the Pasig River flows out to Manila Bay, near the San Nicolas neighborhood. Here is an example of the “salambao” net Lozano painted in plate #14 below. (c/o J. Ramon Faustmann)

Plate #10 - Yglesia Parroquial de Binondo (Parish Church of Binondo). This is when the Church, the Spanish government and the tobacco monopoly were all intertwined. Bldg 1, extreme left, is the Tobacco Monopoly Office; Bldg #2, center, is the actual tobacco factory.

#13 Casa de Campo de Malacañang (A view of Malacañang mansion from the Pasig). A familiar enough view of the residence of all the rulers of the Philippines for over 200 years.

Plate #17 – Esterior de Una Gallera (Exterior of a Cockpit) or a “sabungan” where cockfights were held.

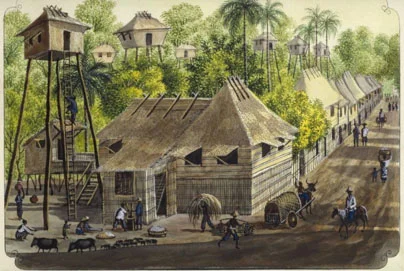

Plate #19 – Casa de un Pueblo en Cagayan (A Typical House in a Cagayan Town) .

Plate #30 – Indio a Caballo (Gentleman on Horseback). Lozano must’ve been in fine fettle the day he painted this. This is one of the finest plates in the whole album. Look at the detail, including shading of the horse (including its brand on its hind rump), of the fabrics, the greenery, etc., the whole scene.

A Fourth Album?

There is supposedly a fourth intact album out there, on the order of the Gervasio Gironella Album. It is the Jose de la Gandara Album, so named after Jose de la Gandara y Navarro, Governor General of the Philippines, 1866-7. It supposedly contains 27 plates, and because it was a commission, i.e., guaranteed compensation for Lozano, it must have been put together with a lot of care and attention to detail. Calle Gandara in old Binondo is named for this Governor-General who also served later as Governor General of Cuba. This album’s whereabouts today, however, remain confidential.

On a rather narrow scope, it was probably under the two previous Governor-generalships—those of Francisco de Paula de la Torre (1843- 44) and Narciso Claveria (the first Count of Manila, 1844-49) that Lozano completed these paintings and compiled into one volume for the short term of office of Gandara.

A Final Mystery

In September 2016, a fifth Lozano album, the so-called Albun de ML (“ML Album”) surfaced at a Salcedo Gallery auction in Manila. It is a smaller folio consisting of twelve (12) plates, dated 1858. (Lozano needed a proofreader.)

Cover of the last Lozano folio sold at an auction in Manila, September 2016.

Its provenance remains a mystery. “ML” stands for the “Marquis of Something.” Salcedo Auctions remains mum about the identity of the Spanish family, per the consignment terms, and that identity was supposedly revealed only, to the presumed new Filipino owner – but which, of course, set me off on another mystery hunt.

Salcedo’s press release at the time titillatingly stated that “’ML’ was an important businessman based in Andalucía who traded in sugar and textiles. He was conferred the title of “marquis” by Queen Isabella II in the 1860’s. The family was also involved in railways, financing and in the liquor, olive oil, soap and real estate industries. ML never set foot in the Philippines and therefore did not commission the album; but it was a gift from a Philippine sugar producer and business partner.

“The heir who inherited the album informed Salcedo Auctions that the paintings were never bound into an album nor framed or displayed as there was no space in the marquis’ palace to hang them. Because of their being kept hidden, the colors are vibrant and no signs of water damage or foxing are seen.”

Given the scant clues, the closest name I came to was a Marques de Loja, one Carlos Marfori y Callejas, born in 1821, at about the same time as Lozano, even though the last Spanish owner was supposedly a marquesa, hence, the woman carries the title today. But the family is Andalusian.

Carlos Marfori y Callejas, Marquis de Loja, 1821-1892. Is he the “ML”?

Was Carlos Marfori (there are Marforis from Davao) “ML”? While I understand that the auction house honors its “non-disclosure” agreement with the consigner, the following questions remain: is the volume one of shameful visuals that one would not like to be associated with? Is there anything criminal or libelous in that volume? (Even if so, the statute of limitations for any regressive legal action would have expired long ago.)

The ML Album is either an earlier set of Lozano works due to their rather primitive, almost amateurish strokes; or he was paid comparatively less for that album, hence, he might have rendered them in very rough strokes as well.

India y Panadero (Local Woman and the Bread-seller) from the ML AlbuM.

The contents of the ML Albun: https://www.facebook.com/salcedoauctions/videos/1453179464709146/UzpfSTEwMDAyMzA0MTUxNjIwMjoyNDc3MDkwMjUyMzQwODYx/

The ML Album sold for Php 6,424,000, US$129,000 (est) at that September 2016 auction.

How much does a Lozano watercolor go for these days?

There is no easy answer. It all depends on several factors: (1) the quality of the piece (there are exquisite pieces and humdrum ones); (2) condition (Well-preserved? Faded? Torn? Water damaged?); (3) size; (4) provenance; (5) the market conditions the day of the auction; (6) its pre-publicity buzz. If it is a rare and major piece, it will be marketed as such, and the collectors with the deepest pockets would have already been alerted—so expect the bidding to be fierce. Do your due diligence and ask lots of questions. A private sale is another matter with its own dynamics.

As a rule-of-thumb, to purchase a nice, quality Lozano today that hopefully, will appreciate over the years, be prepared to have at least $5,000 (Php250,000) in your war chest. With that you could own a beautiful piece of Philippine history.

SOURCES:

José Honorato Lozano - Filipinas 1847 by Jose Maria A. Cariño, Ars Mundi Philippinae, Manila, Philippines, © 2002

Salcedo Gallery Auctions website

Myles A. Garcia is a Correspondent and regular contributor to www.positivelyfilipino.com. His newest book, “Of Adobe, Apple Pie, and Schnitzel With Noodles – An Anthology of Essays on the Filipino-American Experience and Some. . .”, features the best and brightest of the articles Myles has written thus far for this publication. The book is presently available on amazon.com (Australia, USA, Canada, Europe, and the UK).

Myles’ two other books are: Secrets of the Olympic Ceremonies (latest edition, 2016); and Thirty Years Later. . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes published last year, also available from amazon.com.

Myles is also a member of the International Society of Olympic Historians (ISOH) for whose Journal he has had two articles published; a third one on the story of the Rio 2016 cauldrons, will appear in this month’s issue -- not available on amazon.

Finally, Myles has also completed his first full-length stage play, “23 Renoirs, 12 Picassos, . . . one Domenica”, which was given its first successful fully Staged Reading by the Playwright Center of San Francisco. The play is now available for professional production, and hopefully, a world premiere on the SF Bay Area stages.

For any enquiries on the above: contact razor323@gmail.com

More articles from Myles A. Garcia