“Dad in White, Lying Dead on the Tarmac”

/Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. died on the tarmac along with the alleged assassin Rolando Galman.

WOMEN is a group of journalists organized in 1981 by Marra Pl. Lanot, Mila Astorga Garcia, and Jo-Ann Q. Maglipon. Initially, the members came together to hone their craft and critique each other’s writings. But the growing climate of suppression in the country led them to join the struggle for freedom from the dictatorship. They did what they knew best and wrote the stories of fellow citizens stripped of human rights—and some of them paid the price for it. It is a badge of courage they proudly wear today—that they were summoned to military court hearings for their writings.

As had become a regular practice of the group, we met at Odette Alcantara’s lovely and welcoming Heritage Art Center in Cubao, Quezon City. Odette was a feisty woman warrior and, in her later years, an environmentalist with whom we shared many causes. At that August 20 meeting, there was indecisiveness about meeting Ninoy at the airport. We did not wish to add to what was sure to be a large homecoming crowd, and we were absolutely confident that there would be subsequent protest rallies under his leadership that we would certainly join. We felt that at worst, he would be thrown back in detention.

More than three decades later, Ninoy’s death still angers and resurrects anti-Marcos sentiments in many people. Did the regime really feel it could get away with murder, that the citizenry would simply be cowed into silence? August 21, 1983 drastically changed the course of Philippine history, led to the dictator’s undoing, and the return of our democracy.

When one cannot but yield to the strong feelings of antipathy that this nightmare brings, one appreciates and marvels at the absence of negative feelings in Ninoy’s children—President Noynoy Aquino, Ballsy Cruz, Pinky Abellada, and Viel Dee—at the recollection of that day.

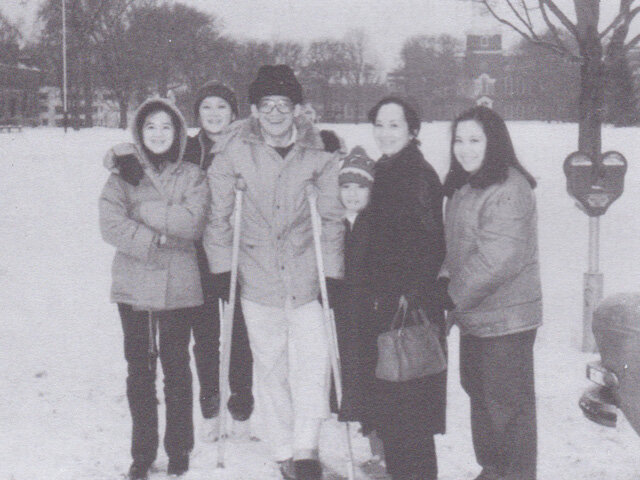

The Aquino Family in America

In his first-ever visit to their Newton home in 2014, ironically on the anniversary date of martial law, PNoy recalled what it was like back then. In an atypical emotional speech in Boston College, he shared:

“In the early morning hours of August 21, 1983, I was watching CNN, waiting to see if they had any news about Dad’s arrival. I will never forget the face of the reporter when he said that, upon the arrival of opposition leader

Benigno Aquino, shots were heard, and he was seen lying in a pool of blood.

This most unexpected news was such a shock that I lost all sensation, and lost track of space and time until the phone rang. I scrambled to get to the phone before any of my sisters or my mother, all of whom were upstairs, could answer it. It was a Filipino-American friend from the West Coast, and by her somber tone, I immediately knew something was wrong, but she wouldn’t tell me anything. When I got upstairs, I found them all awake, and also tuned on to the news, knowing nothing definite, waiting for messages from friends and allies.”

The news was broken to them by Takeo Iguchi, the Japanese consul at the time and a friend of the older Aquino, who heard the news through a Japanese politician, who was informed by a Japanese reporter on the plane with the late senator.

“This was one of our family’s lowest points. As the only son, I felt an overwhelming urge to exact an eye for an eye.”

Viel remembers what it was like for her in their home in Newton, Boston—a comfortable and secure environment that her father left for much uncertainty and danger back home. “I was awakened in the middle of the night with the shocking news and even though it was a very warm summer night (and we had no air conditioning in the room), I suddenly was shivering cold.”

Ballsy and Pinky share (along with many of us) the enduring image of “Dad in white, lying dead on the tarmac.” No other words are needed to convey the tragedy of the assassination, preserved in that timeless image.

It is apparent that, armed with their mother’s deep faith and prayerfulness, they do not dwell on the past and have learned to always look to the future with optimism.

It is a blessing for the family that it was also because of that day that their special long-time friendship with respected theologian Fr. Catalino Arevalo, SJ, began. He was then on leave from the Ateneo and was studying in Boston College across from their Newton home. When an American fellow Jesuit informed him about the assassination, he felt he had to offer his help to the slain ex-senator’s family, whom he had never met. He says he must have met Cory in his youth because his best friend during his Ateneo school days was Monching Cojuangco, a cousin of Cory’s, in whose Baguio home he would spend summers.

Back in Manila, Father Arevalo celebrated the first Mass for Ninoy in October 1983. Since then, he became Cory’s spiritual adviser, and continues to be the invited priest with his thoughtful homilies at family commemorations. Pinky teases that that knock on the door of the Newton home must be a gesture Fr. Arevalo regrets, as he has not been able to walk out again. To this day, the respected Jesuit theologian deeply feels the loss of Cory Aquino, tearing up as he recalls the many conversations with her. All he can say in total admiration and respect is, “I truly miss her.”

It must provide the members of Ninoy’s family much consolation that through the three decades, they have never been alone in their commemoration—long before it became a national holiday. To every celebration of the Mass at the Manila Memorial Park, faithful Ninoy followers from all walks of life come unbidden. Cory would always say that this faithful attendance was heartwarming and beyond all expectations, that the crowd had done its share and when her turn came, it would no longer be necessary to be ever present as well. That has been left unheeded, of course.

Cory Aquino at Ninoy Aquino’s tomb (Source: Al Jazeera)

It is said that when Cory was buying a memorial plot for her husband, she turned down the plots in the more private and secluded areas where the mausoleums of the elite were, saying even then that Ninoy had to be where people could easily visit.

To Ninoy’s children, there is such comfort in the public remembering of a man “who gave up his life so that his countrymen would regain their lost freedoms.” Let his life, and death, ensure that we will “never forget the horrors of a dictatorship and martial law and prevent its repeat.”

What are the lessons learned from their father? Pinky speaks of “his big heart and his love for country and love for people from all walks of life.” Eldest daughter Ballsy keeps those lessons close to her heart—and many others she still prefers to keep mysteriously private.

Life with Ninoy

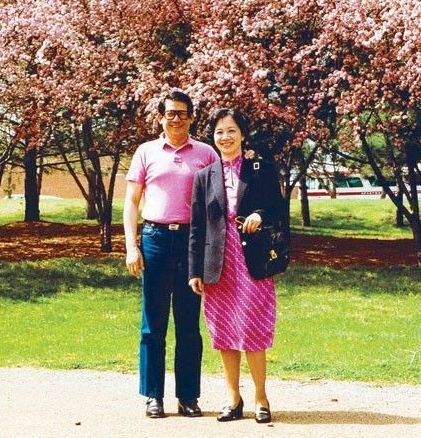

Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. and wife Cory

She, with unusual restraint, had alternately mystified and embarrassed those who openly wept in indignation over the Black Sunday incident at the airport. Could she be for real, many wondered as they bore the anger and the bitterness that this extraordinary widow was expected to manifest, but didn’t.

But then, in Cory’s life, nothing has ever conformed to the normal and the predictable. Once upon a time, when she was seventeen and a freshman at Mount Saint Vincent in New York, a Catholic school run by the Sisters of Charity, she dreamt old-fashioned dreams of a conventional marriage to someone much older and wiser than she. This was why she rebuffed Ninoy’s especially warm airmailed tidings with a stereotyped, “Let’s just be friends!”

Cory had been educated abroad since age thirteen, together with her two brothers and three sisters. Despite the long years in the States, the children came home each year for their vacations. It was at one of the usual rounds of bienvenidas when seventeen-year-old Cory first became aware of this young charmer Ninoy, also seventeen.

“I have done all my crying in Boston. Besides, when you cry, then things don’t get done”

Even so, Ninoy did not quite meet the stipulated age requirement in Cory’s romantic dreams. But that did not discourage him. In true Ninoy Aquino fashion, he merely let time pass quietly. Two summers or so later, Cory had softened, realizing that despite the age deficiency, Ninoy was far more intelligent than any of the older men she had hoped to marry.

Returning home for good after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in French and Math (the unorthodox combination because she wanted to be different), Cory tried to satisfy her perennial fascination with law by attending law classes for a full year and a half. This she had to forego with her eventual marriage to Ninoy.

Tarlac folks deemed the union of two of its most influential families a most fortunate and ideal one. At any rate, it was inevitable that Ninoy and Cory should meet, since Cory’s father, Don Pepe, was the godfather of Ninoy’s sister, Lupita.

Cory and Ninoy had long agreed that they first met at a birthday party of Ninoy’s father. But there was little significance to the event for, Cory laughed, “We were both nine and what do nine-year-olds think about?”

As everyone who knew Ninoy was aware, he was a political, public person and thrived on crowds, while Cory was the exact opposite. Never was this sharp incompatibility put to a greater test than during their first years of marriage—a true baptism of fire, she called it.

A year after marriage, soon after their first child was born, Ninoy was elected mayor of Concepcion, Tarlac. While Cory could not campaign because of her baby, she nevertheless had to live according to people’s expectations of a mayor’s wife.

That meant accompanying the sick to Manila for hospital care with the Aquino car doubling as ambulance, and attending all the wakes in town. What she found the most difficult was visiting the dead and sometimes waiting for coffins to be nailed to completion and having nightmares afterward over such long waiting scenes when the dead seemed as impatient as the living. While devoutly complying with these responsibilities, Cory found herself buttressing her spirit with the thought, “No one forced me into this way of life. I made the choice.”

What also took an inordinate amount of getting used to, especially for a New York-reared girl, was Concepcion’s electric power supply, which was available only twelve hours a day. Most difficult for Cory was allowing herself to be public property. “It was such a small town that everyone minded each other’s business. Everyone knew what we had for lunch,” recalled the very private Cory.

The next and only other time Cory had to campaign more vigorously was when Ninoy ran for the Senate. This seemed imperative, in spite of the couple’s vow early in their marriage that each would continue to do what each could do best: Ninoy, his public service, and Cory, caring for home and children.

Despite what may have seemed a major irreconcilable difference, Cory never felt this was a serious threat to their marriage. It merely seemed the most natural thing that both she and Ninoy had enough old-fashioned sterling love to sustain the complexities of an unconventional marriage. To Cory, marriage meant forever. It was a path she had taken and there was no turning back.

Cory and Ninoy (Source: Philippine Star)

Besides, Cory candidly claimed, “With his charm, you could not stay angry with him for long. He would turn everything into a joke.” For instance, Ninoy had never stopped teasing her for her initial coyness when she first discouraged the infatuated young man. Cory said of that rebuff, “It was probably the only time in his life that anyone ever turned him down.”

On those occasions when Ninoy was into fiery anti-establishment tirades, Cory would go through the often futile motions of attempting to temper him. But speaking as someone who knew Ninoy too well, she said her attitude was one of resignation. “Who can ever dissuade him from doing something once he had made his mind up?” Through all these, Ninoy would remind her, “At least, you can never say there is ever a dull moment in this marriage.” Cory has often told him that she would do anything precisely to get such moments.

It is strange and sad that they had to get away to enjoy such simple joys! Cory remembered fondly the periodic Hong Kong trips (the last one was in 1981) they took as a family, more a necessity than a luxury, for it was during those times when Ninoy suddenly found the time to be with his children all day. On unusual evenings when Ninoy would be relatively free in Manila, Cory and he would go to the movies, any kind of movie, for which they had such a passion. In Boston, the family would complain of the cold or feign sheer exhaustion because Ninoy always enjoyed going out.

The last three years the Aquinos lived in the warmth of family togetherness in Newton, Boston, were idyllic years in many ways, compared with the splintered family set-up during detention at Fort Bonifacio. But it was not all that comfortable and easy at the start. Cory and Ninoy, after somehow having gotten used to living apart, needed to get used to the idea of living together once more. “While the children had only me for so long, there was their father now whom they had to relate to and regard as the authority figure. Especially for Kris who had never known what it was to have a home with a father, this was a special experience.”

“I had to be good at cooking and cleaning to survive in Boston,” revealed Cory, whose lifestyle never required her to do tasks that a retinue of hired hands could so easily do. One of her biggest thrills in the States was eating out just anywhere. For that meant freeing her of one less meal to prepare, and the children, of dishes to wash. Even in a place not in the usual path of tourists, the Aquinos’ typical New England home never ran out of visiting friends who would stay for a day or so. There was such a continuous stream that Cory sometimes wished out loud for disposable beddings.

For extraordinary and hardy as her spirit may be, Cory never aspired to be a stereotyped all-suffering, all-enduring wife. She felt perfectly free to speak out her thoughts to Ninoy, especially when the going was rough.

An inevitability that arose as a consequence of Ninoy’s detention for many years was his loss of employment. While it may be difficult to conceive that a Cojuangco heiress should ever need to reckon with the economics of survival, Cory said this was part of the reality they had to accept. She may have taken comfort in the prospect of security, in having a dear and fortunately large family, both Ninoy’s and hers, to fall back on, should help be truly necessary. Don Pepe had once admonished his children to continue to assist one another especially during times when one of them may, because of certain circumstances, be unable to work. But Ninoy was proud and would not hear of any form of material assistance. “We have always lived comfortably, never luxuriously, and it has always been through Ninoy’s efforts.”

It is this very same openness that has allowed Cory to interpret freely Ninoy’s repeated request in his lifetime that he be interred in Tarlac. To reach a happy compromise because she herself preferred the convenience of visiting the dead in the city, they had agreed matter-of-factly that whoever would be left behind would have the final choice. And Cory felt she had made the right choice, for although Tarlac is a cherished place, one could not visit as regularly as one would want to.

While in Boston, she would wonder out loud to Ninoy what intellectual discussions would again accompany the dinners to which they were invited. It was after all such an intellectual mecca that the usual cocktail party talk would not be “What books have you read?” but “What books have you written?”

Ninoy, observed to have undergone a full flowering of his intellectual gifts during his three-year exile, considered such speculations trivial. This widely-read man would tell her what he had always been convinced of, that whatever form of competition there is in the world all boils down really to the number of books one has read. And Ninoy knew he was far ahead in that race.

On Cory’s part, she felt that her being a good listener went well with what such Boston intellectuals needed. Is she apolitical? Many people have wondered. Cory said, “I may not be a politician. But it would have been such a pity for someone who has been exposed to Ninoy not to be one. I feel l owe the country something.”

Soon after their father’s death, while recollecting their last days of relative tranquility in Boston, the children were regretting that they were not more willing subjects to the newsmen and photographers who flocked to their home, assiduously covering their father’s pre-departure weeks. Then, like Kris and Pinky, they would have had many more recent photos with their dad. Viel, considered to be the shyest of them all, is remembered to have said, “Another photographer again!” and quickly retreated to her bedroom. Though they avoid publicity, they have been taught that their status in life gives them the responsibility to share their blessings with others.

Soon, life did begin to normalize in Times Street. Cory was eager to start life anew, to see her four older kids settled in their jobs, to see Kris adjusted to her life as a seventh grader at the International School. Two days after the funeral, Cory was enrolling Kris at IS, once more lending credence to her brave words, “I have done all my crying in Boston. Besides, when you cry, then things don’t get done.”

The tears may not be evident, but the pain was. Typical of Cory, hers was an inconsolable grief that must be kept private. “I do not wish to cry in front of my children. They have enough pressures to cope with. Other people too seem uncomfortable when they see you in tears.”

People who were heartbroken at the sight of the once fiery and flamboyant Ninoy in his

bloodied bush jacket feared that his appearance may inflict more unnecessary sorrow on his family. Cory saw nothing of what many thought unpretty. “He looked much better than I expected. I guess when you love someone, you only see the beautiful.”

Her heart may have been scarred, even battered—but still she struggled to keep it whole and full.

Neni Sta. Romana-Cruz is chair of the National Book Development Board of the Philippines.

More from Neni Sta. Romana-Cruz