Colonization’s Impact on Manila

/The Americans introduced universal public education, the institutions of American democracy, modern amenities of urban living, and a system of popularly elected local officials; but they did little to alter the inequitable socio-economic structure that the Spaniards left behind.

Similar to the time of Spanish rule, the Philippines was economically exploited during the American regime to support the colonial bureaucracy in the capital city of Manila, and less obvious than during the Spanish era but no less unjust, the country's natural resources were developed to support the commercial and industrial interests of the new colonizer, the United States.

Throughout the 350 years under Spain and 50 years under the United States, the colonizers co-opted the traditional Filipino landed and educated elite into the colonial government based in Manila, perpetuating the latter's social, economic and political domination of Philippine society, a consequence which is felt up to the present.

Who would have imagined almost four centuries ago that out of the palisaded Muslim settlement of some 2,000 inhabitants, Manila would emerge as an urban complex? With its strategic location at the mouth of the Pasig River and Manila Bay, Manila was initiated by the Spaniards into its role as the gateway to the Americas, attributing to it an urban dimension. Since then it has dramatized its importance in world affairs, confirming the geographic reality that it is strategically and centrally located on the world map.

But if Spain contributed to the fertilization of the Philippine heritage and the “Europeanization” of its environment, America further invigorated it with the Anglo-Saxon way of life, the “city-beautiful” concept, and the English language.

Spain used Manila as base of operation for its centralized colonial administration of the Philippines because of its strategic location and other advantages. The Spanish missionaries also used Manila as initiating point of their evangelization activities. When the Americans took over the reins of colonial power, they maintained Manila as seat of government and center of economic activities.

Placed at the apex of colonial rule for almost 350 years by Spain and 45 years by the United States, Manila has been entrenched as Capital and hub of political, economic, cultural and religious transformation of Philippine society under the aegis of colonization.

The historical development and transformation of Manila and its surrounding areas mirrors that of the entire nation. Many of its problems fostered by centuries of colonial rule and its slow and erratic socio-economic growth continue to afflict present-day urban life, greatly affecting national development. In order to understand and appreciate its contemporary problems and challenges, it will be helpful to look back briefly at certain events in its history that planted the seeds of many of its present conditions.

The Roots of Urbanization

Manila was a thriving barangay (local term for community) of some 2,000 people when the Spaniards found it in May 1570. Like Manila, small, relatively isolated barangays were already existing in the Philippines long before the Spaniards came. Headed by a chief called datu, these communities were social units or kinship groups rather than political units. They had subsistence economies with agricultural production geared mainly to the needs of the community. These needs determined to a large extent the pattern of land use and landholdings which were communal. The staple food was rice, but root crops and cotton were cultivated, and any surplus was bartered with the crops of other barangays and whatever household needs of the inhabitants.

The Spaniard’s image of Manila Bay when they first arrived in May of 1570.

Among the barangays, Manila had indicated prominence much early on. Historical records show that the rulers of the barangays in pre-colonial Manila seemed to have formed the nucleus of a trading and commercial community at the mouth of the Pasig River. Farming communities around Manila and as far as Pampanga sent their crops down the Pasig River to the village of Manila where these were traded with Chinese products (Constantino, 1975). However, since trade was at a relatively small scale, the economy of Manila and surrounding barangays remained largely at subsistence level.

Although the first Spanish settlement in the Philippines was established in Cebu by Miguel Lopez de Legaspi in 1565, the scarcity of food supplies forced him to move, first to the island of Panay and later to Manila in May 1570 based on a favorable report from Martin de Goiti who learned of the busy port of Manila from the Chinese and other Asian traders. Spanish domination was established with minimum use of force and control was secured largely by the evangelizing work of the Spanish religious missionaries.

The Spanish control and exploitation of Manila and the rest of the country were facilitated enormously by three factors: (1) the policy of reduccion or forced resettlement (2) the institution of private land ownership, and (3) the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade.

The Policy of Reduccion

Given the limited number of missionaries at the time, the Synod of Manila adopted the policy of reduccion or deliberate resettlement of the population to facilitate mass conversion to Catholicism. The process involved requiring dispersed barangays to constitute into compact but larger communities and reducing their number (thus the term ‘reduccion’) so that they can be easily and quickly called to attend church rites and be accounted for their regular contributions. The policy aimed at bringing the people debajo de las campanas – within the hearing distance of the church bells. Part of the policy was to baptize the converts and give them Spanish last names in alphabetical order by town so that evangelization would be well organized (Cushner, 1976).

Reduccion greatly aided the organization of local government in the country. It laid down the pattern of present urban settlements in the Philippines with the church, bell tower and convent occupying a prominent place in the town center together with the municipal hall, which became known as the “town plaza complex” in 20th century urban design parlance.

Privatization of Land Ownership

Perhaps, the most significant, far-reaching, and enduring instrument the Spaniards introduced that has altered Philippine economic and social structure is the institution of private land ownership. Before the Spanish arrived, land ownership was largely communal and land use was based on usufruct rights. Private property, as established by the Spanish colonizers, is evidenced by the possession of a title, which was a form of wealth. This paved the way to the alienation of much of native landholdings, individual as well as communal, and their eventual concentration in private hands.

Stringent rules governing real estate transactions were promulgated by the Spanish colonial regime to prevent the fraudulent transfer of native landholdings and the sale of communal lands. However, the disruption of barangay communities due to the enforcement of the policy of reduccion often obscured the distinction between private and communal landholdings. These rules were also frequently unenforced.

The Spanish governors-general gave land grants, which often included communal lands, to Spaniards and native principales. Members of the principalia (former datus,, their families and descendants) also sold or donated lands over which they assumed private ownership but were actually communal lands. Ignorance of the new laws governing private land ownership, coupled with traditional deference for the principalia (who had become local officials in the colonial bureaucracy), repeatedly resulted in the Tagalogs’ (natives of Manila) loss of hereditary individual and communal landholdings (Cushner, 1971).

The rise of large land estates around Manila was stimulated by the increasing profitability of agricultural production because of the city’s expanding population. Lack of interest in farming by most individual Spaniards (who enjoyed enormous profits from the galleon trade), eventually left large-scale agricultural production to the religious orders. By the 18th century, the religious orders were the biggest landowners around Manila. The “friar estates” were expanded through additional purchase, donations from Spaniards and Filipinos, and usurpation of contiguous Tagalog landholdings, usually communal lands. The new landholdings by usurpation were easily legitimized by government resurvey and payment of a fee.

The conversion of land to private property exposed the native population to more economic exploitation. Fundamentally, it changed the structure of indigenous society. As the Tagalogs lost their individual and communal lands, they became tenants, share-croppers, and paid or unpaid farm laborers, who were ultimately pushed to revolt against their foreign exploiters. The personal and economic insecurity that hounded the Tagalogs became the harbinger of the land problems underneath whose weight the Filipino peasantry is still struggling.

The Manila Galleon Trade

Manila’s initial wealth was derived from the profitable trade between Acapulco, Mexico and Manila, known in colonial times as the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade. The Galleon Trade was the first and biggest monopolistic trade between Asia and the Americas. Bigger than the British, French, and Dutch East India Companies trade with Europe, it thrived for almost two and a half centuries. The trade began in 1565, and until 1813, the galleons sailed regularly each year from Manila to Acapulco, bringing oriental goods and returning with mail from Spain and silver from Mexico.

The Philippine trade with China, which antedated the Spanish conquest, was the foundation of the Manila-Acapulco Trade. During the latter part of the 16th and early 17th centuries, some 30 to 40 Chinese junks came to Manila each year, laden with silk and other textiles, porcelain, fruits, farm animals and others goods. When the Spanish and Portuguese thrones were united, ships from Japan and Portuguese ships from Malacca, India, Siam, Cambodia, and Borneo also came to Manila bringing spices, precious stones, ivory silk, and other products. These products were loaded into the galleons and brought to Acapulco. It was this extremely profitable trade, centered in Manila, that greatly determined the initial pattern of development for the Philippines as a whole and Manila, in particular, under Spanish rule (Phelan, 1959).

Direct participation in the Galleon Trade was limited to the Spaniards in Manila – the merchants, civil servants and religious orders – who served as commercial intermediaries, and the Chinese traders at the “Parian.” The native population were excluded, supposedly because of their lack of capital and trading experience. As the Spanish merchants kept their capital invested in Manila, the economic prosperity brought by the Galleon Trade was largely confined to Manila and its suburbs. The Spanish Manilans (the Insulares) lived comfortably from the profits of the trade, while the Chinese in Manila were the middlemen, acting as consigners, providing credit to merchants, packing the merchandise for the galleons, engaging in retail trade and providing a variety of skills needed by the urban population.

The continued influx and prosperity of the Chinese was assured by the dependence of the Spaniards on their services. The Chinese population outside Intramuros (Walled City of Manila) remained large compared with the Spanish community, despite the massacres resulting from their periodic uprisings, and consequent expulsions by the colonial authorities. The Chinese were confined in the community of Binondo, now Binondo district of Manila, which is recognized as the first and biggest Chinatown in the world. Nevertheless, during most of the 250 years of the Galleon Trade, the Chinese were able to secure control of the internal retail trade and credit facilities in the country, becoming a dominant economic group. Unlike the Spaniards, the Chinese had more intermarriages with the native population. The offspring of these marriages – the Chinese mestizo – became the leading entrepreneurs during the period of economic development in the 19th century. Intramuros – the Walled City - was built during the heyday of the Galleon Trade. It was a section of Manila that was fortified to secure the Spaniards and keep out the native Filipinos and local Chinese. It linked the Philippines with Spain and the outside world, and served as the seat of government and administration, ecclesiastical center, military outpost and center of inter-island commerce and foreign trade. Manila’s rapid development and affluence during the 16th and 17th centuries depended totally on the prosperity of the Galleon Trade, forced labor, tribute tax, and forced purchase of agricultural products from other parts of the country to support the colonial bureaucracy based in Manila.

Manila Bay and Intramuros,as visualized by the Spaniards in the mid-1800s.

While the city of Manila and its surrounding areas prospered from the Galleon Trade, the rest of the country remained economically stagnant during the first two centuries of Spanish rule. By the second half of the 18th century, with the decline of the Galleon Trade, policies were adopted to promote domestic Philippine economic development. Increased production of cash crops accelerated the concentration of ownership of agricultural estates in the hands of the select few who became the new landed gentry (the hacienderos). Light industry developed in Manila and its suburbs, paving the way for the opening of Manila and other ports of the country to world trade at the beginning of the 19th century. Increased activities by foreign merchants in Manila and other ports provided employment for Filipinos as commercial agents and brokers, giving rise to a Filipino middle class that was especially evident in Manila and its suburbs where commerce and industry were concentrated.

By the second half of the 19th century, the Philippines had become primarily an exporter of agricultural raw materials and importer of manufactured goods. Rice production shifted to production of profitable export crops, causing rice shortages in the country. With foreign competition also leading to the destruction of traditional textile and other industries, there was consequently widespread economic dislocation and suffering among agricultural and urban workers. Social unrest was fueled further by the abuses of colonial and religious authorities, and conflicts between and among the Insulares (Spaniards born in the Philippines), the mestizo class, and the Peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain who were regarded as elite).

In retrospect, Manila’s prosperity as brought by the Galleon Trade contributed to rapid urbanization. Its expanded population stimulated agricultural production and industry around its area. Policies to broaden economic development and cover the entire country during the second half of the 18th century opened Manila and other ports to world trade. These new developments basically established the foundation of the present-day structure of Philippine economy and society and its relations with foreign countries. However, these changes came with a heavy price especially for the majority of Filipinos.

The American Regime

The victory of Commodore George Dewey at Manila Bay on May 1, 1898 paved the way for a half-century of American rule. Like the Spanish colonizers of 1571, American soldiers occupied Manila on August 13, 1898 and gradually established authority over the whole country. To subdue the provinces, they used the strategy of re-concentration, which the Spanish government used in Cuba and which the American government had criticized. The Filipino-American War lasted over three years, but the sporadic resistance to the new regime continued for many years.

The Americans introduced universal public education with English as medium of instruction, the ideals and institutions of American democracy, and modern amenities of urban living. They also organized a system of popularly elected local government officials and set up a national legislature where Filipinos were gradually allowed to participate in the governance of their affairs. However, the Americans did little to alter the basic socio-economic structure that the Spaniards had left behind (Agoncillo, 1969).

Calle Rosario, Binondo, Manila, 1926

In fact, a major reason for the bitter mass resistance against the American forces was the betrayal of the Filipinos’ hopes for economic and social emancipation. Under the United States Constitution and the Treaty of Paris, the right to private property in the Philippines was to be respected. The friar lands that were confiscated by the short-lived Philippine Republic were therefore returned to the religious orders – the Dominicans, Recoletos, Augustinians, and Franciscans. As Jacob Schurman, Chairman of the First Philippine Commission, admitted: “This was a bitter pill for the Filipinos, who had taken up arms and shed their blood primarily with the object of expelling the friars and confiscating their property. The Treaty of Paris bilked them of the dearest object of their rebellion.”

The much-heralded purchase by Governor William Howard Taft of friar lands in 1903, supposedly to be subdivided and sold to tenants of the estates, was not accompanied by a program of financial assistance to the peasants. Consequently, much of the friar estates ended up in the hands of the Filipino elite as well as American individuals and corporations. The Americans coopted the traditional Filipino principalia into the colonial government based in Manila, perpetuating the latter’s social, economic and political domination of Philippine society. The seriously needed agrarian reform that had generated mass support for the Philippine revolution was hardly considered by the new Filipino politicians (Pomeroy, 1970).

During the American regime, the country was developed purposefully into a primarily agricultural support economy. As control over the Philippine affairs passed from the United States President to Congress, economic policies in the Philippines became dependent on the degree of Congressional support that vested American interests in agriculture, labor, commerce, and industry could muster. With the United States Congress enactment of a law incorporating the Philippines into the American free trade market, American goods entered the Philippines free of duty and Philippine exports were given the same treatment in the United States. Consequently, demand for Philippine agricultural exports, particularly sugar, increased, making large agricultural estates even more attractive.

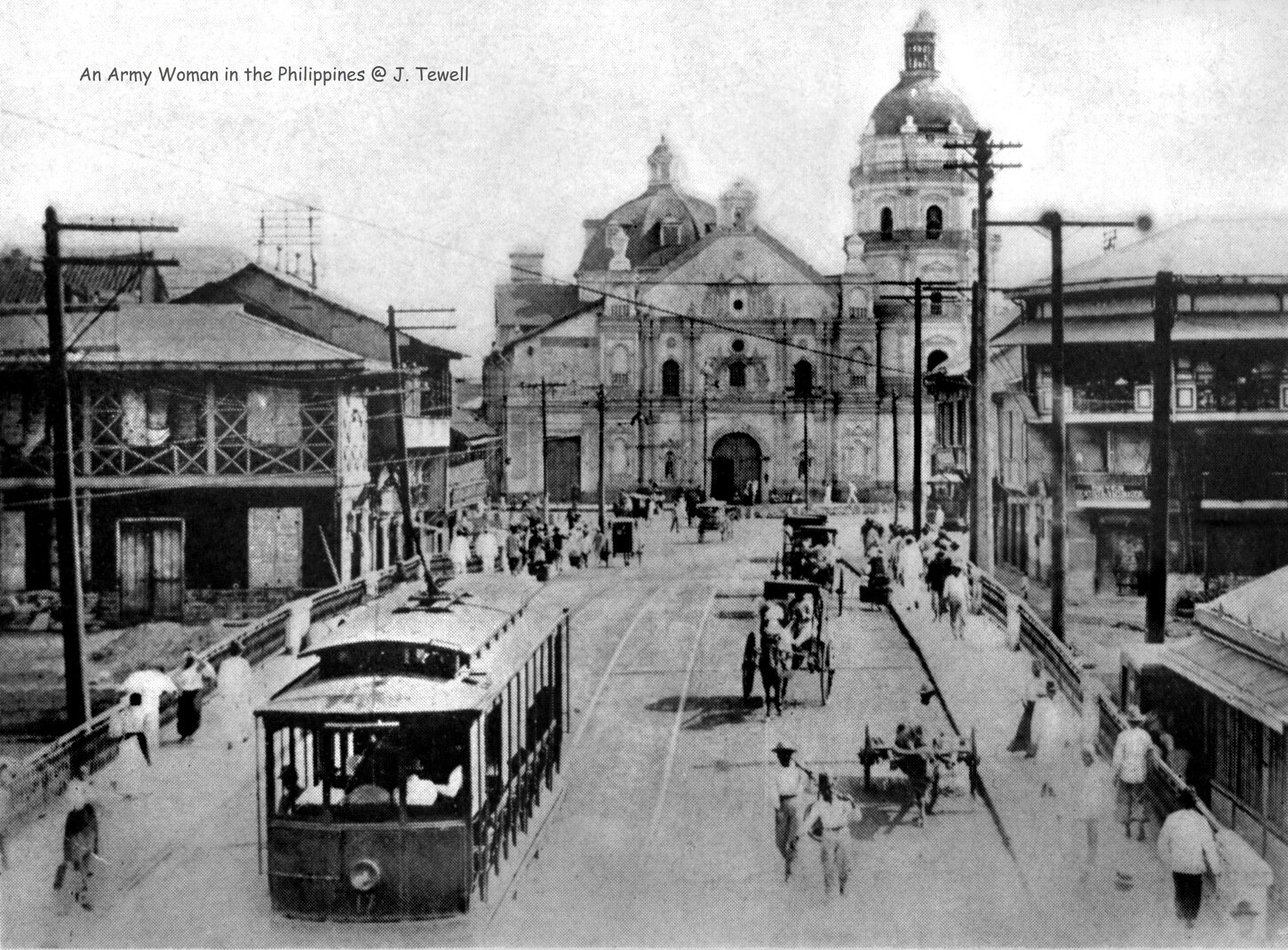

Binondo Church, Tranvia over San Fernando Bridge, 1914.

The influx of American manufacturers and goods into the Philippines, along with the infusion of American values in the public school system, developed consumer preference for goods “made in the USA” among the Filipinos. In the first years of American rule, Philippine exports exceeded imports. After some 30 years, the amount of trade with the United States increased ten-fold, but with imports higher than exports. At the end of American rule, the Philippines remained a “one crop economy almost entirely dependent on the United States as market and supplier of manufactured goods.”

Similar to the time of Spanish rule, the countryside was economically exploited during the American regime to support the colonial bureaucracy in the capital city of Manila. Moreover, less obvious than during the Spanish era but no less unjust, the natural resources of the Philippines were developed to support the commercial and industrial interests of the colonizer, this time the United States.

Manila remained the colonial capital under American rule. The influx of American officials, soldiers, teachers, and businessmen into the city led to the immediate construction and improvement of urban amenities. New roads and bridges were built. Manila’s harbor was modernized. Parks, public recreation areas, social clubs, drinking bars and other attractions the Americans were accustomed to were developed. The new amenities and attractions altered very much the city’s landscape.

Tranvia and Autobos routes of the Manila Electric Railroad and Light Company in 1932.

Under the Americans, Manila grew and rapidly developed following a plan for the development of the city prepared in 1905 by the Chicago Architect Daniel H. Burnham. However, the rapid rise in Manila’s population resulted in slum dwellings as the cost of urban land and the cost of living increased. There were several attempts to effect slum clearance, particularly in Tondo and Binondo, but no remedial action was taken by the Philippine legislature during the Commonwealth government. There was a comprehensive plan for slum clearance in Tondo in 1933, but a study found that only 40 percent of the slum dweller families had incomes that would enable them to buy or rent low-cost and most basic houses. With more government studies on housing, the Legislature appropriated funds to construct low-cost houses for laborers mostly in Quezon City since it had a much bigger land area than Manila. However, because of other government priorities and lack of political will this plan was overtaken by the outbreak of the World War II.

Burnham Plan for Manila

American policies still sustained the dependent development of the Philippine economy and society even after World War II. Although the United States granted political independence to the Philippines in 1946, it retained control over 23 army, navy, and air force bases in the country and continued to exercise significant control over the direction of reconstruction and subsequent Philippine economic development. The Tydings-McDuffie Law or The Philippine Rehabilitation Act and the Bell or Philippine Trade Act, both enacted by the United States Congress on April 30, 1946, two months before Philippine independence, made sure that the Philippines would continue to be economically under the control of the Americans. The two laws restored the status quo of the Philippines before the war, by perpetuating the country’s dependence on the United States as market of its select cash crops, as source of raw materials critical to the US economy, and as consumer of American manufactured goods (Shalom, 1980).

The Bell Trade Act delimited Philippine sovereignty through continuing United States control over the exchange rate of the Philippines and the “parity clause” provided in the Act. The parity clause would subsequently be used to exert influence on the direction of the country’s economic development. It directly affected the formulation of national economic and development policies. The parity clause of the Bell Trade Act provided that: “The disposition, development and utilization of all agricultural, timber, and mineral lands of the public domain, the waters, minerals coal, petroleum, and mineral resources of the Philippines, and the operations of public utilities, shall, if open to any person, be open to citizens of the United States and to all forms of business enterprise owned or controlled, directly or indirectly, by United States citizens.”

Filipino leaders were divided in their reaction to the Bell Trade Act. On one hand, traditional exporters hailed the continuation of their privileged treatment. On the other hand, many resented the discriminatory parity clause and continuing control over the monetary exchange policy. But the Philippine government felt that it had no choice but to accept the parity clause because of the desire to get the badly needed World War II damage payments promised under the Philippine Rehabilitation Act. Free trade with the United States not only perpetuated economic inequality, it also fostered the continued political dominance of the traditional landed and educated elite of Philippine society, a consequence with lasting significance for the government of the city of Manila.

The war years had resulted in massive destruction of the city and greatly reduced its population. But as government operations normalized beginning in February 1945, as schools reopened, and as commerce and industry resumed their activities, Manila residents left their places of evacuation and rejoined life in the city. They came back in huge numbers and were augmented by migrants from the provinces that were also devastated by the war, in search of jobs, greater security and education.

Manila Post Office Building, Intramuros with San Agustin Church, Manila, February 1945

The rapid and massive influx of people overwhelmed whatever capacity government had in catering to people’s needs. Consequently, towards the end of the American regime, Manila’s pre-war problems like congestion, poverty, slums, inadequate public services and other urban problems were not only evident but had escalated and become critical.

An excerpt from the author's book, Metro Manila: My City, My Home. The book is available through its publisher Assure at http://www.assure.ph.

References:

Agoncillo, Teodoro A. A Short History of the Philippines. Mentor Books. New York and Toronto: The New American Library, Inc., 1969.

Constantino, Renato. The Philippines: A Past Revisited. Quezon City: Tala Publishing Corp., 1975.

Cushner, Nicolas P. Landed Estates in the Colonial Philippines. Monograph Series No. 20. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies, 1976.

Cushner, Nicolas P. Spain in the Philippines: From Conquest to Revolution. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc., 1971.

Phelan, John Leddy. The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565 – 1700. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1959.

Pomeroy, William J. American Neo-Colonialism: Its Emergence in the Philippines and Asia. New York: International Publishers, 1970)

Shalom, Stephen R.. Philippine Acceptance of the Bell Trade Act of 1946: A Study of Manipulative Democracy. Pacific Historical Review, Vol. XLIX, No. 3, 1980)

Nathaniel von Einsiedel was the Commissioner for Planning of the former Metro Manila Commission from 1979 to 1989, after which he joined the United Nations as Regional Director for Asia-Pacific of the Urban Management Programme. He returned to the Philippines in 2004 and has since been Principal Urban Planner of CONCEP Inc., a private consulting firm specializing in sustainable urban development and management.

More articles from Nathaniel "Dinky" Von Einsiedel