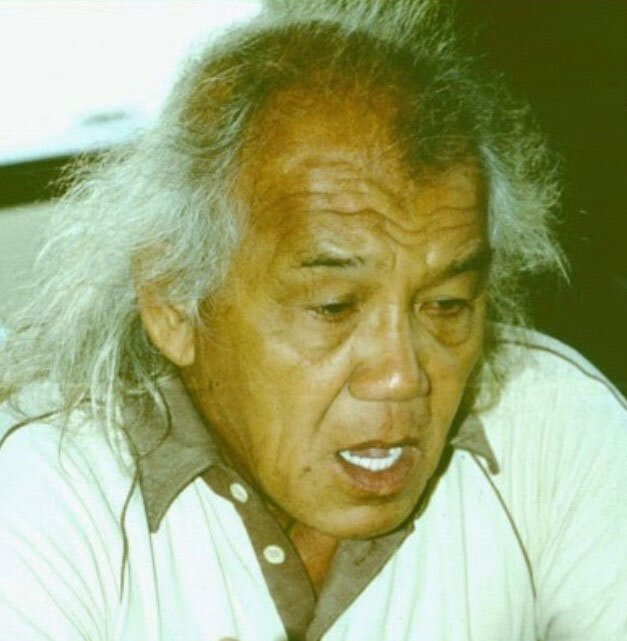

Cesar Climaco: The Life and Times of a Democracy Icon

/Mayor Cesar Climaco’s funeral march (Photo by Robert Lim)

Along the 10-kilometer uphill route of the funeral march, mourners displayed protest placards and streamers, tossed confetti and flowers, and sang songs of defiance and sorrow. It was the largest political demonstration ever witnessed at any time in the troubled island of Mindanao.

Since President Marcos declared martial law on September 21, 1972, government military forces had battled constantly with two insurgent armies – the communist-led New People’s Army (NPA) and the separatist Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), aside from dealing, with an iron hand, with countless protest actions in the cities. Thousands had been killed or disabled, many more rendered homeless, and innumerable others suffered from abuses committed mainly by government troops.

At the southwestern tip of Mindanao island, Zamboanga City, whose blend of Islamic, Spanish, and indigenous cultures shrouded it with an irresistible charm and ambience that delighted residents and visitors alike, was transformed. The upgraded presence of the South Command military headquarters turned the city into the most militarized in the entire country. At any given time, at least 1,500 soldiers in full combat gear patrolled the city streets.

Ironically, the overwhelming presence of the military in Zamboanga also corresponded with the rise in criminal activities. Armed robberies, killings, shootouts, and bombings became commonplace. Syndicates engaged in extortion, smuggling, piracy, kidnapping, and highly profitable but illegal businesses proliferated and became more powerful.

In the midst of this rapidly deteriorating peace and order situation, Cesar Climaco presided over a civilian administrative system whose powers had been sharply reduced by Marcos’ decrees. Control and supervision of the local police had been transferred to the Armed Forces. Referring to Zamboanga’s monicker as “The City of Flowers,” Climaco retorted: “We now have more guns than flowers.”

Early Life

Born on February 28, 1916 in Zamboanga City, Cesar was the third of seven children of Gregorio Borromeo Climaco and Isabel Dominguez Cortes. His father had been municipal councilor of Zamboanga and his mother worked as a schoolteacher and wrote for a local newspaper.

Climaco family in 1930s (Cesar is on the left) (Source: Climaco family archive)

Belonging to a lower-middle class family, Cesar supported himself through high school as a worker asphalting roads. After graduation he was employed as a timekeeper, messenger, and janitor. Moving to Manila, he continued to be a working student while studying pre-law at the University of Santo Tomas and his law degree proper at the University of the Philippines. He alternated as a domestic house help, driver, and tutor to a well-off family, and a janitor at the Court of Appeals. He passed the bar in 1941 as one of the topnotchers.

Cesar was assistant secretary to the Davao mayor and later Justice of the Peace in Siasi, Sulu. After the 2nd World War, he became Secretary to the Zamboanga City mayor. Elected City Councilor in 1951, he was then appointed acting city mayor two years later. In 1955, he became the first elected mayor of Zamboanga and was re-elected in 1959.

Mayor in the ‘50s

Climaco brought into the public service a new style of leadership that was to become his lifelong trademark. Rejecting the glitter and trappings of public office, he dressed simply and often drove his own jeep on frequent city inspection tours. Declaring that he already owned a house, Climaco refused to collect the monthly allowance he was entitled to. He also never used the official car assigned to him, preferring his own trustworthy old jeep.

Mayor Climaco in the 50s (Source: Climaco family archive)

Climaco strived hard to be a model public servant and demanded no less from other city officials and employees. His crusade for good government antagonized various vested interest groups and incurred the ire of powerful sectors. He once personally led a raid on hotel rooms occupied by internal revenue agents and discovered smuggled goods in 15 suitcases and bags. Climaco was always the first to arrive at the scene of any crime, accident, or calamity – ahead of police officers.

He already displayed a satirical wit even then, an irreverent humor, a propensity for practical jokes, and a brashness that elated his constituents and friends but anguished protocol-minded bureaucrats. He habitually inspected police outposts at night where he would sometimes chance on policemen sleeping on the job. To teach them a lesson, he would “steal” their typewriters, caps, and even their arms and present these “stolen goods” to them the next day.

As a national official

His performance as city mayor gained national prominence and he was drafted to run as a senatorial candidate of the Liberal Party in 1961, 1963, and 1965. Lacking the financial resources, he narrowly lost in all of them.

In between these electoral contests, Climaco served in various national offices as Administrator of the Office of Economic Coordination (a Cabinet post), Commissioner of Customs, Presidential Assistant on Community Development, and head of the Presidential Anti-Graft Committee. He maintained high standards of honesty, dedication, and service, refusing to bow to pressure from politicians and other influential persons. As a result, he never lasted long in any of these positions.

“Ever the mischievous politician, he put up as his headquarters a shanty hut beside his opponent’s opulent campaign office and put up a sign: “We don’t buy votes here, try next door.””

As Customs Commissioner, he once withheld the release of an imported car bought by a ranking congressman of the ruling party unless the full duties were paid. Realizing the extent of graft and corruption at the bureau, he was constantly at the port area, personally inspecting incoming and outgoing goods. He even brought a cot to his office so he could sometimes stay overnight and keep watch over Customs operations.

As the Presidential Assistant on Community Development, he traveled to remote villages and emphasized the importance of people, not projects, and pushed the goal of attaining self-reliance and resourcefulness. As Presidential graft-buster, he made newspaper headlines when he pronounced his own office “impotent” and recommended its abolition.

Climaco taking his oath before President Diosdado Macapagal in 1964 (Source: Climaco family archive)

Back to Zamboanga amid social unrest

With his party out of power after 1965, Climaco returned to Zamboanga and turned to farming. He envisioned cooperative farms as one answer to rural poverty. Unlike most landowners, he willingly subjected his farmland to the land reform program. In the meantime, he was still being regularly sought for advice, consultation, and help by people from all walks of life, especially the poor.

Social unrest, meanwhile, was brewing in the country. A militant and nationalist student and youth movement arose, which often took to the streets to denounce government excesses and subservience to foreign interests. Marcos’ second inauguration in 1970 after an election marked by widespread irregularities, overspending, and misuse of public funds was greeted by violent protest demonstrations in Manila.

The economy was badly battered by mismanagement, misdirected policies, and excessive electoral spending. The peso was devalued and prices of goods and services increased several fold. In 1971, Marcos was bailed out with loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Marcos was becoming increasingly unpopular and isolated and the opposition Liberal Party, of which Climaco was a National Executive Committee member, confidently prepared to re-assume power in the upcoming 1973 elections. But Philippine politics was now moving towards a new and frightful stage.

On August 21, 1971, a grenade attack at a Liberal Party rally killed many innocent people and seriously injured the party’s leaders. Climaco, fortunately, was not on the stage and as he helped to carry the victims to ambulances, pronounced before television cameras the death of democracy in the Philippines.

The formal institutions of democracy, however, would linger on for one more turbulent year. Within this period the protest movement grew more militant and attracted greater numbers from disenchanted but more politicized young people.

An ongoing Constitutional Convention saw nationalist members gaining support for new provisions that would sharply reduce foreign dominance over the economy and interference in internal politics. In the rural areas, the presence of a new rebel army of a revitalized Communist Party was being slowly felt.

“He started by unleashing a torrent of letters and telegrams to Marcos and other civilian and military officials denouncing martial law practices and abuses.”

Martial law

Prohibited by the Constitution from running for a third term, Marcos announced before a stunned people the proclamation of martial law on September 21, 1972, ostensibly to counter a “growing communist threat.” All political parties and mass organizations were banned, opposition leaders were jailed and held without trial, and civil liberties and political rights were suspended. With Congress padlocked, Marcos also assumed legislative powers.

Pre-martial law Philippines was no paradise. The economy was basically agrarian and underdeveloped, industrial development was at a standstill, politicians acted like medieval warlords with private armies, and poverty was widespread.

But democratic processes were still at work as represented by press freedom, civil liberties, an independent judiciary, a balanced Congress, and most important of all, popular mass organizations of different classes and sectors of society. Martial law, however, completely decimated these formal institutions and processes.

Higher stage of Climaco’s political career

Authoritarian one-man rule brought Cesar C. Climaco’s political career to a new and qualitatively higher stage. Martial law would mark a crossroads, a turning point in his political life. In previous years, his main concerns were good government, graft and corruption, and bureaucratic inefficiencies.

After 1972, and without losing sight of his past campaigns, Climaco now focused on higher ideals and principles such as democracy, human rights, and social equality. He started by unleashing a torrent of letters and telegrams to Marcos and other civilian and military officials denouncing martial law practices and abuses. In addition, he reproduced and widely distributed these documents. Issued at the rate of once or twice a day, they constituted passionate chronicles of the evils besetting the country.

The language of these letters reflected Climaco’s combative spirit. They were often tactless and direct, gross and risqué and always spiced with humor and satire. These messages were also, in reality, Climaco’s way of reaching out to the Filipino people as well as peoples of other countries. Unable to resist a playful stab at Marcos, he also vowed not to cut his hair until martial law is revoked.

In the early years of martial law, when many people were silenced by the threat of harassment, detention, or death, Climaco was among the few who dared to openly resist Marcos’ authoritarian rule.

Climaco confronting President Ferdinand Marcos and his wife, Imelda (Source: Climaco family archive)

Testing the political waters in 1978, he ran for the reconvened legislature (Interim Batasang Pambansa) but lost due to massive poll irregularities. In the 1979 regional elections, he got back at the ruling party by fielding as a candidate a known “town simpleton” who actually garnered thousands of votes. This practical joke conveyed a message loud and clear – that elections under martial law cannot be treated seriously.

Climaco, however, was prevailed upon to lead his party once more in a bid to recapture the city administration in the 1980 local elections. Working with meager campaign funds, he won by a landslide over his Marcos-backed opponent, the controversial and moneyed Maria Clara Lobregat.

Mayor during martial law

As city mayor, Climaco continued his crusade against the abuses committed by those in uniform. He blamed martial law and one-man rule for the breakdown of democracy, the loss of the citizenry’s civil liberties, and the economic crisis ravaging the country.

His detailed and publicly distributed letters of complaint to Marcos and other civilian and security officials centered on human rights violations by the military and police, their impotence in solving crimes, and their alleged protection of illegal businesses and gambling. In these letters, Climaco hinted that the military itself was involved in the killings, bombings, and grenade-throwing incidents.

The common people regarded Climaco as their protector and defender and they ran to him whenever they needed help for anything – a son who had been unjustly detained, a farmer who was being ejected from his land, a missing relative or friend. In all of these cases and countless others, the mayor always stood on the side of the poor, the disadvantaged, and the oppressed.

Rejecting suggestions to assume a lower public profile and employ armed bodyguards, Climaco retorted that a mayor who cannot protect himself cannot protect the people. He was thus an easy target for any would-be assassin. Alone, he would roam the city streets on an old motorcycle, his long white hair trailing in the wind, toting bags of candies for the children along the way.

Climaco on his trusty motorbike (Photo by Robert Lim)

His office and house were open to everyone. No appointments were needed to see him. He would welcome and entertain foreign ambassadors and market vendors with equal graciousness and courtesy. Even the most trivial of complaints he listened to and immediately acted upon.

Climaco’s disputes with the military command did not prevent him from relating to rank and file soldiers. Some enlisted men even sought his assistance as they had been victims of abuses from their own officers. His sense of fairness and compassion often overcame his quest for retribution for military misdeeds. After having secured the detention of soldiers accused of atrocities, he visited them and seeing the appalling conditions of their confinement, he wrote a strong letter of protest to the Southcom chief.

Despite receiving several death threats, Climaco refused to compromise his principles and became even more emboldened in his campaign for truth, justice, democracy, and freedom.

Brewing National Crisis

All over the nation, signs of a serious and debilitating economic crisis were slowly creeping on an already suffering people. While the foreign debt was reaching unmanageable levels, public funds were being spent on glamour and image-building projects, in huge behest loans to Presidential “cronies,” or were carted away in secret foreign bank accounts.

Land reform was a dismal failure, and farmers reeled under the high costs of imported inputs. Industrialization remained superficial and dependent on foreign suppliers and markets. Social inequalities widened and incomes of the working class fell below subsistence levels.

Despite announcing the formal lifting martial law in January 1981, Marcos retained legislative powers, rendering the administration-dominated Congress a mere rubber stamp.

The Aquino assassination aftermath

The event that finally brought the crisis to a breakpoint was the shocking airport assassination of the returning opposition leader Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino, Jr. while in military custody. An outraged citizenry reacted by joining massive protest demonstrations. Large sections of a previously unconcerned population were suddenly awakened. The middle class, for the first time, joined students, workers and urban poor in demanding justice for Aquino and for all other victims of state violence. A common cry reverberated: “Marcos, Resign!”

In Zamboanga, the brazen killing of his friend and close political ally deeply affected and incensed Climaco. In addition to organizing and leading mass actions, he put up an imposing Aquino shrine in a city park the inscription of which the Southcom military commander found offensive to Marcos. Despite military pressures, Climaco refused to take down the shrine.

In Manila, the political stability of the Marcos government was threatened. Foreign and local businessmen began transferring their assets to foreign banks. Reserves fell to dangerous levels, prompting the government to declare a moratorium on foreign loan repayments and seek standby credit from the International Monetary Fund.

Defying restrictions, street protests continued demanding the government’s resignation. Marcos was losing control over the situation. It was in the context of this multiple crises and the upsurge of popular participation in the political process that elections for the regular legislature were held in May 1984.

The 1984 Legislative elections

Although distrustful of elections under Marcos, Climaco nevertheless realized that the new political conditions provided the opposition with better chances of victory even in the midst of widespread cheating. It would be Climaco’s last political campaign.

Declaring his objective to be the dismantling of “one-man rule” he turned the elections into an entertaining political circus with his wit at its sharpest and his creativity at its height. Ever the mischievous politician, he put up as his headquarters a shanty hut beside his opponent’s opulent campaign office and put up a sign: “We don’t buy votes here, try next door.”

At the end of the colorful and uproarious campaign, the people of Zamboanga elected Climaco with more votes than the combined total of his two administration-backed opponents. He fulfilled a campaign promise to postpone taking his seat in the legislature, deciding to serve out his full term as mayor and saying that it was a more important role than that of “a legislator in the world’s largest and most expensive rubber stamp.”

The victories by a number of opposition candidates in the May 1984 elections placated a restive citizenry and gave Marcos some breathing space to refurbish his tarnished image. A government-appointed fact-finding board on the Aquino assassination also rejected the official version that Communists were responsible and eventually named as co-conspirators the Armed Forces chief of staff and two other generals.

But the unrest refused to die down and the economy deteriorated further. The 1984 inflation rate would reach 60 percent, the highest in 25 years. Protests would become more militant and were often violently dispersed. Workers’ and transport strikes would paralyze businesses, especially in southern Mindanao and in metropolitan Manila. Bank runs created panic among depositors.

In Zamboanga City, violence escalated as killings, robberies, and kidnappings remained unsolved. Military and police officers vied for control over profitable business concerns such as the barter trade, the arrastre service and gambling and entertainment.

In Zamboanga City, Climaco intensified his crusade against the Marcos dictatorship. When a jeepney drivers’ strike in Manila ended successfully with Marcos granting their demands, Climaco admiringly called the strikers “heroes” and called for the heightening of the mass civil disobedience movement. He urged the people to learn from the jeepney drivers and plan for a general strike to bring the country’s activities to a full stop.

Climaco and his jeep (Photo by Robert Lim)

Climaco’s Assassination

By late 1984, Climaco was feeling the net that government forces were weaving closing in on him. The mysterious killing of a police lieutenant and the shooting of a lawyer, both Muslims, a few meters from his residence, prompted Climaco to issue a public warning that the two incidents would be used as a pretext to do away with him under the guise of a Muslim vendetta. He accused the military of spreading the rumor that he was responsible for the two shooting incidents.

In the early morning hours of November 14, 1984, Climaco was awakened by a report that a fire had broken out in an urban poor community in the downtown area. As usual he was the first on the scene. As he was alighting from his motorcycle, a lone gunman approached from behind and fired a single shot at the back of his head. He was dead on arrival at the hospital.

Acting on cue, the military pointed to the brother of the slain police lieutenant as the killer. But the Climaco family and Zamboanga residents firmly believed that, as in the Aquino killing, the military was involved. If this was the case, they said, the mayor’s murder may never be solved. And, indeed, 36 years later, Climaco’s assassins remain unidentified.

Climaco’s legacy

In 2008, Climaco was inducted into the Bantayog ng mga Bayani (Pantheon of Heroes) -- a shrine in Quezon City honoring those who gave their lives fighting against the Marcos dictatorship. In 2012, the National Historical Commission conferred on Climaco the Rizal Award in ceremonies commemorating the national hero’s 150th birth anniversary. On September 21, 2018, the 46th anniversary of the proclamation of martial law, the Philippine Commission on Human Rights enshrined Climaco into its honor roll of a select group of martial law martyrs.

Cesar Cortes Climaco

Cesar Cortes Climaco’s ideals and struggles remain relevant and meaningful even more so today. The country reels under a pandemic that has taken thousands of lives. Misguided and inadequate government responses have resulted in the country’s worst economic performance in over 70 years. Poverty, joblessness, hunger, and inequality have worsened. Human rights violations have increased. A de facto authoritarian set-up appears to have been put in place.

Under such appalling conditions, the best and most fitting tribute to honor Cesar Climaco’s memory is to carry on his unfinished work and resist efforts to restore authoritarian rule that would revive the ghosts of the Marcos past.

Eduardo C. Tadem, Ph.D., is a retired Professor of Asian Studies, University of the Philippines Diliman. He is a nephew of Cesar C. Climaco. This article is revised from a presentation at an online Forum on “CCC’s Legacy” on November 14, 2020, organized by the Ateneo de Zamboanga University, School of Liberal Arts.

More articles from Eduardo C. Tadem, Ph.D.