Carol Varga: When She Was Bad, She Was Very, Very Good

/(Photo courtesy of Carol Varga)

(Originally published in Filipinas in April 2003)

Pure serendipity, that’s how.

Carol Varga finished high school at the all-girls St. Theresa’s College in Manila. Like other teenyboppers in the early postwar years, she loved partying and dancing the jitterbug. At one party, she caught the eye of the actor Leopoldo Salcedo, who invited her and her friends to a gathering of movie personalities. There, she made an impression on one of the celebrities in attendance, the actor Bimbo Danao, who not only suggested she try her luck in the movies, but also helped pave the way.

Danao then introduced Varga to Don Jesus Cacho, the owner of Lebran Productions, one of the leading movie companies at the time. After passing the screen test, she was offered a contract.

To launch her career, Cacho and company went about looking for a screen name. During the brainstorming session, Cacho’s teenage daughter, Marilou, entered the room, and upon learning the business at hand, suggested that the newcomer be named “Varga,” after the Varga Girl, a popular illustrated pinup in Esquire, a magazine for men. That was how Carolina Encarnacion Vizconde Trinidad became Carol Varga, and a legend was born.

(Photo courtesy of Carol Varga)

In her first movie, Siudad sa Ilalim ng Lupa (Underground City), Varga was an ingénue.

In her second movie, The 13th Sultan, which was in English, she played the role of a princess. It was memorable because it was during this time that she met, fell in love, and became engaged to an American entrepreneur.

Varga’s third movie with Lebran was Sagur. Then, her fiancé was killed in circumstances that made sensational headlines. Suddenly, Varga was embroiled in a huge scandal. She went through several interrogations by different law-enforcement agencies, and was later asked to testify in court.

The fourth movie with Lebran, Kalbaryo in Hesus (Calvary of Jesus), where she played the wife of Pontius Pilate, seemed to parallel the turmoil in her personal life. It was also the last movie she made with Lebran, which folded shortly.

Her father, who did not approve of her movie career from the beginning, was livid when he learned about his daughter’s involvement with the dead American. The scandal, which lasted for two long years, branded Varga with notoriety and practically ruined her movie career. Consequently, none of the movie studios wanted anything to do with her.

Not one to whine about her fate, Varga turned to the stage. She toured the Philippines, appearing in variety shows. Because she could not sing, she did skits and dances instead. Joe Collado, an engineer in Metro Manila, remembers, “When I was a child in my hometown, Ballesteros, Cagayan, I saw her perform onstage at one of the local high schools. She was good!”

“She was better at playing a villain whose heart and soul were filled with evil.”

However, the public humiliation had taken its toll. Varga was hurting emotionally, and, as if playing a melodramatic role, turned to alcohol for refuge. It was during this dark period in her life that history would repeat itself. Leopoldo Salcedo, who had by then become the undisputed “King of Philippine Movies,” saw her at a nightclub, and seeing her condition, advised her to shape up and get her act together. More than that, he offered Varga a lead role in Highway 54, which he was producing. The movie was based on a real-life story, and Varga played the part of a bandit queen. Her performance was very strong. The movie audience apparently noticed, too—Highway 54 was a box-office hit!

Varga’s career started blooming again. Premiere Productions offered her a contract, and she worked with the studio from 1953 to 1963. In her first movie with Premiere, she played the role of a scorned woman in Dyesebel, which starred Edna Luna and Jaime de la Rosa and was directed by Gerry de Leon. In the movie, Varga is a socialite engaged to de la Rosa, who subsequently falls in love with Luna, a mermaid. The movie ending is pure poetic justice. Luna becomes human, whereas Vargas morphs into a mermaid! Dyesebel was a runaway hit and became a Philippine movie classic.

For much of her stint at Premiere, Varga played supporting roles, which she did not bother her one bit. She was always busy, appearing in practically every movie the studio produced. Moreover, when a movie bombed, the lead stars and the directors were blamed, but never the supporting cast. Thus, she got away with her stature intact.

As part of the stable of actors and actresses at Premiere, Varga had to adhere to the strict guidelines that the studio manufactured for the wholesome public images of its stars. Once, she found herself being reprimanded for violating the dress code, that is, wearing slippers, in public. Although acting took up most of her waking hours, Varga says she had a life outside work. She stayed away from studio cliques, preferring instead to hang out with her friends, who were mostly college students.

In one movie, Varga tried playing the role of a woman of virtue. She realized very quickly that it wasn’t easy. She was better at playing a villain whose heart and soul were filled with evil. She could play a socialite, a bartender, or the other woman to the hilt, but playing mother superior did not come naturally. And she could not play a destitute or a born loser with any credibility.

Franklin Bobadilla, a bibliographer in The Hague in the Netherlands, observes, “The moment she appeared in a scene, the audience knew right away that she was up to no good. When she released her venom, she put Lucifer to shame!”

“Oh, she was vile!” recollects Evelyn Doris Abao, who is a Philippine National Bank executive in Manila. “But she had style, even in the way she smoked. She would move her shoulders a certain way and puff a cigarette arrogantly. Nobody could smoke onscreen the way she did.”

If there is a Carol Varga School of Smoking Onscreen, there is also a distinctly Carol Varga Method of Acting. “She would be laughing hysterically,” explains Bayani Recio Legaspi, a public-health nurse in Chicago. “And then, suddenly she would go into uncontrollable sobbing fits. Now, that was always a showstopper!”

Carol Varga demonstrates the Carol Varga School of Smoking Onscreen. (Photo by Rey E. de la Cruz)

“Subtlety was never part of Carol Varga’s repertoire,” notes George Garma, an antiques dealer in the Los Angeles area. “She was extreme in the true and every sense of the word.”

Chicago-based visual artist Willi Red Buhay expounds on the Carol Varga mystique: “Her contemporaries, Rosa Rosal of LVN and Bella Flores and Zeny Zabala of Sampaguita Pictures, were equally wicked. But La Varga was in a league of her own. Who could forget those bangs and red lipstick? She had that sinful image permanently etched onscreen She appeared in black-and-white movies, but you could just tell that her lips were oozing bloody red”

Varga has also influenced fashion. Philippine newspapers and magazines have featured the “Carol Varga look” in their fashion spreads. Models have reenacted diabolical scenes from her movies, wearing trademark bangs and red lipstick.

Elena Buensalido Mangahas, a community leader in Stockton, California, exclaims, “ Carol Varga’s the one and only patron saint of Philippine camp! People love Carol Varga! They couldn’t get enough of her. She has become an inimitable icon!”

Varga has been immortalized in the world of art. Imelda Cajipe Endaya, a visual artist in New York and Metro Manila, made an artwork entitled Santa Kontrabida (St. Baddie), of which she gave a copy to Varga. In the digital print, Varga, with horns, dismembered body parts, and her usual sneaky smile, is juxtaposed with an image of a kneeling female saint with a halo.

What’s next? “A shrine!—there should be a shrine in her honor,” replies Binky Feliciano, a fashion designer in Metro Manila. “Carol Varga is the ultimate vamp—the epitome of Philippine antagonism!”

Although Varga was a character actress, her acting was sterling because she disappeared in the stereotyped bitchy roles she played. In 1955, Varga received an acting award from the Filipino Academy of Movie Arts and Sciences (FAMAS), the Philippine counterpart of the Oscars, for her supporting role in Guapo (Handsome).

Nowadays, Varga, who has resided in Las Vegas since 1968, is amazed at the hoopla over her. “Acting was a job that I did well. I never imagined people would remember me to this day.” She is married to Carl Richard Harley, with whom she has a son, Carl Benjamin Harley.

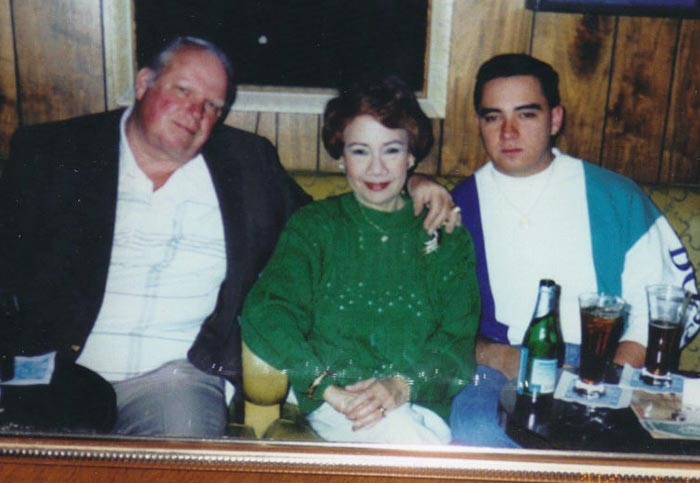

Carol Varga with her husband, Carr Richard Harley, and son, Carl Benjamin Harley. (Photo is courtesy of Carol Varga)

She is amused when told about her large gay following. However, it did not surprise her. “I am a people person. I talk to anybody. At work or at play in the Philippines, I always had excellent rapport with gays,” she recalls. “There used to be a gay area in Sta. Cruz (a district in Manila), which I used to drive to and visit. Every time I arrived, somebody would shout, ‘Carol is here!’ Then, almost everybody in the neighborhood would come up to welcome me.”

A painting of her in a Ruben Panis terno holding her FAMAS statuette is prominently displayed in her living room. “I have few memorabilia of my movie days,” Carol Varga says. “But people would send me photos and clippings of me that they’ve collected through the years. I’m thankful for people thinking of me. They love me, and I also love them.”

A painting of Carol Varga in a Ruben Panis terno holding her FAMAS statuette for her supporting role inGuapo (Handsome). (Photo is courtesy of Carol Varga)

How would she like to be remembered? “People can remember me with any image,” she replies. “If they don’t want to remember me as an angel, that’s fine with me.”

Update: Carol Varga passed away in Las Vegas on March 8, 2008.

The author wishes to thank Rheez Chua (Manila), Angioline A. Loredo (New York City), and Dr. Edward A. Tuico (Houston) for their assistance in the rare interview.

Rey E. de la Cruz, Ed.D., writes from Chicagoland when he is not loving the arts and traveling. He is the author of the children’s book, Ballesteros on My Mind: My Hometown in the Philippines, which also has Ilocano, Spanish, and Tagalog versions.

More articles from Rey E. de la Cruz