Camino Portuguese, a Walk for All Ages

/The Camino de Santiago is also known as Saint James Way, the "Way," or the Jacobean Routes. Since the 10th century, pilgrims have walked to the Cathedral in what is now Santiago in Spanish Galicia where the relics of Saint James were buried. The most difficult slog is the Camino Frances, 500 km over the Pyrenees, and may take 30 days, at least. Others, we've heard, have started from Germany, or Sevilla, Spain, where it would cover at least 1,000 km. There are an estimated 1,000 daily arrivals in Santiago. Each arrival is recorded for history. An official certificate called a compostela is issued, and their names are read during the pilgrims’ Mass at noon. Not everyone, though, gets a compostela. You must complete at least 100 km of walking, with stamps on a passport (credencial) as proof.

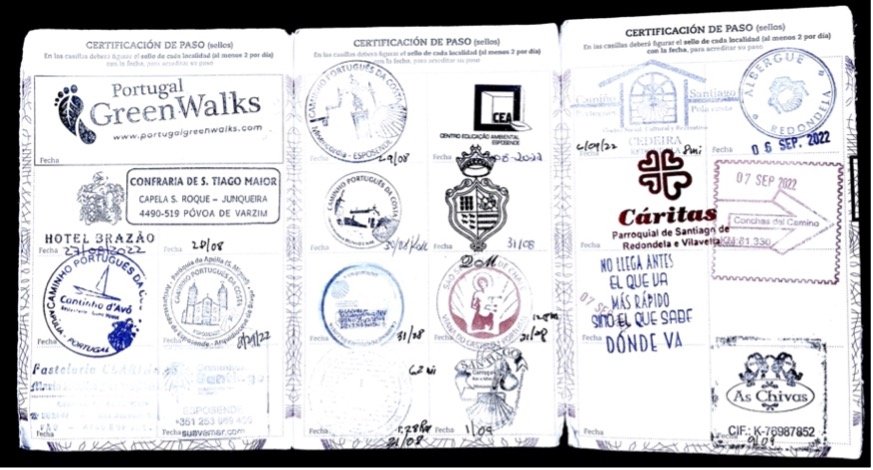

A fully stamped credencial (sellos)

After 21 days of walking, still wet from a previous drizzle, we stood in line at the Acogida de Peregrinos (Pilgrim's office), staring at the form we needed to complete for a compostela. To receive this official certificate, a person behind the counter will do a short interview about your Camino experience. Our compostela would be evidence of our pilgrimage. We would become part of a historical tradition that began a thousand years ago. Since the 10th century, during the Middle Ages, millions of pilgrims have walked to Santiago de Compostela. They came to seek indulgences, be healed, or make life promises in the presence of St. James’ relics housed in the Cathedral. In more recent years, the Camino has become more secular and touristy (although we met some groups praying on the trail) no doubt romanticized by films like Martin Sheen's "The Way" and "Tres Caminos."

"What purpose did you have to do the Camino?" The form listed: Religious - Spiritual- Tour -Sport- Cycling. I checked Spiritual, as did Patricia. He then looked at our passport, a booklet of stamps gathered at each stage of our journey. Two stamps each day from churches or establishments were proof of arrival. Our fully stamped passport showed 260 km. Satisfied, he made the final stamp and inscribed our names in Latin on the certificate. Mine became Michaeleum, and Patricia's became Patriiceum.

Planning the Camino

Patricia and I were always fascinated by pilgrimages. In our younger years, we observed and studied the pilgrimage to Mount Banahaw, in Southern Luzon. It was a great way to see the land and meet local folks. There were hardly any amenities at the time. Visiting the sites and climbing Mt. Banahaw was arduous and demanded endurance. Belief in the journey itself and the physical accomplishment were its greatest rewards. We were barely in our forties when we charged up the crater of Mount Banahaw with our pilgrim guides. We figured that The Camino would reflect a similar experience three decades later. The journey would take us to Portugal and Spain, which was high on Patricia's travel bucket list, especially since she had not been to these places.

Self-doubt nagged at us as we contemplated the walk of our lifetime. Two hundred kilometers of unfamiliar terrain, unfamiliar Portuguese language, and unfamiliar customs: what if we get sick or have an accident in the middle of the path? Can we get lodgings at the end of the day? Do we have to trek at nightfall? Or basic questions like-are there restrooms along the trail?

Patricia's research yielded answers ranging from excellent advice to impractical ones. It pointed her to a U.K.-based Camino agency specializing in the senior market, Portugal Green Walks. They promised environmentally sensitive tours as well.

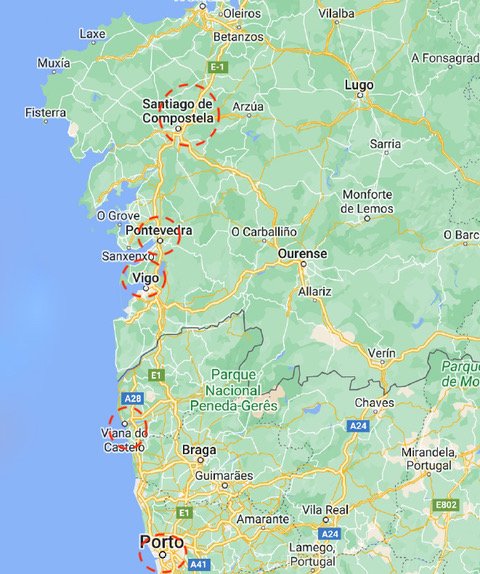

Based on our requirements, they suggested we follow the Camino Portuguese, or the Coastal Route. They pre-booked our lodgings, arranged luggage transfers, and would just be a phone call away for emergencies. As it turned out, such concerns (as one would anxiously have if traveling around the Philippines) were unwarranted. Throughout the walk, especially in Portugal, cafes with expresso, sandwiches, or restrooms were available roughly two hours apart. A backpack with 1-2 litter water bladder, almonds, and a sunblock cream are essential, as are comfortable hiking shoes, a hat, and walking poles. The latter, we discovered for seniors like us, were a knee saver.

Much can be said about traveling in Portugal now, although our intention was not to be tourists. We arrived in late August, during the European holidays' last weeks. The sun was not as intense, and rain clouds loomed on the horizon. Although we understood and spoke Castilian, we were advised to best use English. The Portuguese were eager to speak English, it turned out. Even then, they know when to offer help. The ticket lady offered a senior discount at the train station, something we were unaware of. After that, our public transport expenses were cut in half! The more we interacted with the local folks, we quickly grew fond of Portugal.

We spent a day in the lovely city of Porto, lodging not far from the Sao Bento train station.

Rebuilt from a monastery into a Beaux-Arts edifice over a train station, the lobby is clad in more than 20,000 azulejos (tin-glazed blue ceramic tiles) depicting the history of Portugal. Azulejos, we discovered, is the signature art form of Portugal, and its manufacture was sponsored by royalty. A short walk from the station, we chanced upon the "Blue Chapel" (Chapel of Souls) that was fully clad in azulejos. One wall was inscribed with "San Francisco." We could not help taking a selfie for posterity.

Chapel of the Souls, Porto

We were ready for slow travel, as some writers would call it and the main reason we chose to visit Portugal and Spain by walking. Doing the Camino, we experienced three modes of walking: sauntering (old French: a la seinte terre), trudging, and slogging the walk of a lifetime.

Boardwalks, Forever

It looked like a pleasant hike based on what we gleaned from tourist brochures and sundry blogs. Where practical, the government has installed wooden boardwalk skirting miles and miles of Portugal's beautiful Atlantic coast. It starts at the edge of Lisbon's coast to as far as Caminha, ending at the Rio Minho, which separates Portugal from Spain. It is a beautiful example of civic infrastructure of wooden planks that wind gracefully along the coast. It’s enviable. We wished California had something of this magnitude. Our appreciation grew for the Portuguese government’s forward-looking urban/seascape planning for its citizens.

At one juncture of the boardwalk, we spotted a modular reading room that served as a beach-front library. Books for beachgoers! We could see their enjoyment as we greeted each one we met on the boardwalk with a pleasant "Bom Dia!" that was reciprocated with a smile and a greeting, "Buon Camino!" (Happy Trails).

August 30, 2022. Starting out from Labruje, Porto. The shell symbol and yellow arrow marks the “Way of St. James.”

Miles of well-maintained boardwalk as far as you can see wind down the Atlantic coast.

Most of the walk was pleasant, with many coastal views, quaint streams, historic bridges, farming villages, and grape pickers (video). Towns went by in a blur. Others were memorable and sometimes made more so with a tasty dinner.

Pain Management

We kept a ritual for the three weeks: Wake up at 6:30 to get dressed, re-pack our luggage (with a knee on it to force the zipper) for pick up by luggage transfer, and get ready for breakfast. Breakfast was simple, brightened by other delights depending on the quality of the hotel – pao (bread), jam and butter, jamon serrano, slices of Spanish sausage, coffee, and juice. A few hotels have additional items like scrambled eggs, fruits, yogurt, or pastries. Lunch depends on what time we reach a town. Before we headed out, we would stop by a cafeteria and order some ham sandwiches. These would be our lunch on the trail. We often reached a town at 2 p.m. when most kitchens have shut down and wouldn't open until 7 p.m. (the Spanish "siesta"). Some cafeterias will oblige a hungry pilgrim at least with an egg torta and some bread. Dinner is ready at 9 p.m.

Unfortunately, the lateness conflicts with the schedule the pilgrim who must wake up early. To save time, we often skipped a full meal and looked for a place serving soup and salad. Anticipating these needs, Patricia packed mixed nuts in Ziplock bags that we could munch on the trail to stave off hunger pangs while searching for dinner.

There is an unspoken tradition that peregrinos should be treated well by the community. They take special notice if you are a Camino pilgrim. The scallop shell on your backpack is your ID. You can always show (or be asked) your pilgrim's passport to get a pilgrim's menu (an inexpensive four-course meal).

The Camino Portuguese, with its spectacular coastal views and wonderful people encounters, was an unbelievable experience that we continued to process weeks after our trek. Our most considerable burden was the 15-lb backpack: a liter of water, a spare shirt and socks, snacks, and first-aid provisions. With each mile we walked, the backpack seemed to get heavier and heavier. We envied the younger trekkers who would pass us on the trail like it was just an afternoon stroll, the sound of their walking poles tapping on the pavement to hurry us from behind.

The “Eiffel bridge” at the foot the mountain we had to cross to reach Viana do Castelo seen from the Monastery of Santa Luzia.

While in Portugal, most of the trails were on the boardwalks. Towards Spain, the trail became a combination of freeway sidewalks (scary), uphill tarmac, uneven cobblestones, and rock and boulder trails. The walking pole proved to be our best friend. You get a little push for an uphill climb and use it as a brake on the downhill. It aided your balance while negotiating the rocky downhill trails. The walking poles saved our knees and ankles and took off some weight from our backpacks (estimates say the load is reduced by 15%)

Caldas de Reis was an ancient Roman town known for its hot water baths.

Negotiating Spain

By the time we reached the Spanish border, the walking was taking its toll. Although the Camino was well marked either by painted yellow arrows or permanent metal or tile arrow signs, they were not always visible along the road. Sometimes, it misdirected us, so we would retrace our steps. Although the boardwalk and yellow tarmac were easy to walk, our route would also take us inland, where the terrain was more unexpectedly rough. We did not train for that. Nor did we prepare for rain.

Kilometer marker with Camino direction arrow with stones on top, said to be a sign of unburdening

Before the Camino, we trained daily for a month, walking 7-10 miles up and about the Stanford hills. On the Camino, the average distance between towns is eight to nine miles, and the longest stretch is 15 miles. We figured that if we trained for 10 miles, we should be able to complete 15 miles. The reasoning was sound and proved correct, but we did not anticipate backpack weight. Worst, the cobblestones and boulders in the forest's trails were rougher than we imagined, and then, the rain.

We knew about the cobblestones but, being rural roads, they were not all evenly laid out. Tripping over one, or worst, twisting an ankle, was anxiety-causing and slowed us considerably. When a car drives on the cobblestones, they create a frightening sound like a jet plane taking off as a car speeds down the narrow one-lane streets. And speeding they do in Portugal and Spain.

The worst trails were the smooth boulders that covered the mountain trails. Fortunately, it was dry the first two weeks we were on the trail. The boulders would otherwise have been dangerously slippery. With a 15-lbs backpack, you could quickly lose your balance, land on your knees, and smash a kneecap. That would be the end of it. Heaven forbid, I would pray silently as I gingerly threaded my way out of the maze of boulders.

Sometimes the trail was somewhat spooky. We were, at times, in a thick forest of eucalyptus and pine that would take sharp corners. In the early mornings, when the air was still foggy, while I lingered and took photographs, Patricia would disappear from view as if the forest swallowed her up.

Camino trail through the forest

But what caused us great hardship was the rain. Not just a drizzle but heavy downpours.

By the time we reached Baiona, Spain, there were threats of stormy weather throughout our last week. We caught our first downpour en route to Vigo outside the city and got soaked to the bone.

We reached the outskirts of the city, reasonably exhausted, soaked, and short of time. We needed to make a decision. If we continued walking, we would reach the city center (known for its hilly streets) at nightfall, passing through urban street traffic. Rather than invite an unsafe situation, we rested at the nearest park to call our tour manager for advice.

Miraculously, a taxi drove up just as I was describing the situation. We quickly hailed it and clambered in, grateful for the piece of luck. Luck indeed, as the driver explained that he just decided to leave the taxi stand to head back to the city (a taxi might refuse to drive out of the city on a one-way fare).

Pinoyspotting

Filipinos who travel abroad are known, like it or not, to engage in pinoyspotting. We were no exception. Up until then, we had not seen any Filipino Camino walkers. There was a Chinese group from New Jersey; a Japanese woman on her own and an East Indian father-daughter trekker. No lack of Asians (for a very Western European activity). We've heard that the Camino has become popular among Filipino travelers, hence our curiosity.

Our first encounter was serendipitous (very characteristic of the Camino experience). After crossing into Spain and a night in A Guarda, we walked towards the town of Oia. Trudging on cobblestones, we passed through a small-town teeming with weekenders. The recommended Café Henriqueta was full. Ahead was another restaurant A Camboa Tapaceria, with a snobby waiter. He wasn't interested in us unless we ordered a sit-down meal. Claiming our pilgrim status (and the need for a restroom), we were seated in the bar. It turned out to be fortuitous. An old man who was anxious to chat with me was signaling at the other end of the bar. While Patricia ordered an expresso and a bottle of peach juice, the old man gave me his spiel on the Camino. He had come as an immigrant from France and worked in the fields. Pointing at a monastery on the hill ahead he said that its thick walls prevented pirates from overcoming it. He saw us, with our backpack and scallop shells, as captive audience to regale us with his Camino adventures. The Camino map on the wall served as his illustration. Mindful of our schedule, I indicated that my expresso was getting cold and excused myself. Patricia had also ordered caramel cheesecake and flan, the first we had during the Camino. The flan reminded me of Mama Lydia's flan. It was a sweet reward after a long tiring walk.

Continuing our walk, we stopped at a beach-side café (another plus of the Camino Portuguese is its well-provisioned beaches). Since we were in Spanish territory, I had no hesitation in speaking Castilian. “Quiremos cha y chocolate, por favor,” I asked the café lady. She lighted up hearing Castilian from a P-O-C. While Patricia and I waited at the table outside, a young lady of slightly mestiza complexion came up and asks, "Are you from the Philippines?" "Yes!" I answered with surprise. "I'm Filipino half-German!" she excitedly announced. We saw them earlier on the trail but did not make the connection. There were quite a few young women on their own, enjoying the safety of the Camino. "My mom's Filipino. She's from Mindanao! I figured you're Filipino, when you spoke Spanish. My mom used to. She was a schoolteacher, but she's forgotten it." Karen was from Munich and traveled with her friend Lisa, starting from Lisbon airport, a few more miles from where we started. We exchanged notes and told her to tell her mom that my group exhibits textiles from Mindanao. Later, she calls her mom on her cell about us. They were on a fast-track 7-day trip to Santiago. There's work waiting, she said. As we bid our goodbyes, she asked a young American named Joseph to take our photo.

With Karen and Lisa

The only other time we met Filipinos was in Pontevedra. Pontevedra was the convergence point of pilgrims from different routes. It also marked the 100 km range required to earn a compostela certificate. Along the trail, we met and chatted with Jose. He resides in Mexico but occasionally visits his daughter in Madrid. During this visit, he took the opportunity to do another Camino. We struggled hard to keep pace with him. He carried very little, a small backpack and a bottle of water. We pulled back and told him to not be held back by us.

Meeting Filipinos on the Camino

After a few hours, we reached the next town where refreshments could be had. Lo and behold, there was Jose. As soon as he saw us, he called out, saying, look who I found? A Filipino couple, Marisol and Jonathan, having merienda at the table with Jose. We quickly struck up a conversation. They were from San Francisco and traveling with a Vietnamese orthopedist friend, Henry. They will continue to Verde Islands after Compostela, they told us. Like Jose, this was their second Camino, having done the Camino Frances before. Other Filipino friends we know have also done the Camino Frances route. It was the more popular route for Filipinos trekking in mostly Spanish territory. I invited Jonathan to visit our San Francisco museum when they returned. Hopefully, they do. That was the last sighting of Filipinos we had until we reached Santiago.

Closing In on Santiago

Our anxiety now was how much rain we will encounter towards Santiago. We still had nine miles to go. Before our last stage, we spent the night at a beautiful inn that served first-class dinners.

We also had a chance to launder our clothes inexpensively. Despite the thunderstorm that would last the entire night, we slept rather soundly.

After an early hearty breakfast, we headed out in the drizzle. On the trail, squalls came and went. Sometimes we had forest cover. Other times we were caught in the open. The first town we reached outside Santiago, Miladoiro, was God-sent and provided a respite from the rain. At the first café we found, Patricia had tea, and I had my hot chocolate. Sufficiently replenished, we slogged in the rain towards Santiago and into the old part of town. From a distance, we could see the church spires guiding us.

As we followed the yellow arrow signs, the groups of pilgrims were getting thicker along the path. The rain was pouring relentlessly. We walked past older buildings along Rua do Franco, past cafés full of tourists, past the 500-year-old medical university, and into the grand plaza. People were milling about and taking selfies. There was much cheering, and the shrill music of bagpipes filled the air.

We turned to the right and saw the Cathedral. We were soaking wet but exhilarated. After 21 days, we felt an enormous sense of relief. Twenty-one days of walking 260 km. We celebrated with a selfie. It was noon of September 13, and we arrived safe and sound. No blisters, no mishaps. Well, not quite. Exhausted, I had a fever by evening. The next day, Patricia developed a cough. Minor discomforts in the face of what we accomplished. We collected our official compostelas, then joined the community of pilgrims for evening Mass held in our honor. "Buen Camino!"

The Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

Postscript

Hollywood, Netflix, and YouTube have popularized many experiences about the Camino. The key to a pleasant Camino is a good night's rest (quiet surroundings) and, oddly enough, foot care. Should you do it, your experience would be different from ours as everything is relative (for example, how much off track from the Camino). Those who seek an authentic pilgrim experience should try the inexpensive alberques (dorm-like hostels, average prices 10-12 euros). Clearly, we avoided these for good reasons. Our favorites may be your opposite. Buyer beware. EU hotel ratings also do not correspond to US hotel ratings. In our opinion, an EU 3-stars is a notch better than a US 3-stars. At times, some are more elegant. EU hotels are also cheaper, perhaps to catch up with the drop in travel during the pandemic. Except for one hotel, most breakfasts are standard "continental" although some hotels do better than that.

Our favorites were: Lisbon (Hotel Alegria); Porto (Hotel Liberdade); Apulia (Cantinho D'Avo); Esposende (Quinta Do Monteverde); Ancora (Hotel Meira); Baiona (Hotel Anunciada); Vigo (Hotel Oca Ipanema Vigo); Pontevedra (Hotel Virgen del Camino); Caldas de Reis (Hotel Balneario Acuna); Padron (Pazo de Lestrove); Teo (Casa Parada de Francos); Santiago (Hotel Monumento San Francisco). These hotels provide excellent breakfasts.

Most decent meals will be under 35 euros. For 21 days, $100 a day might be average, depending on your dinners. Not all hotels offer dinners. At a restaurant, you can ask for a menu peregrino, a 4-course meal for less than 20 euros (egg-potato torta, salad, fish or chicken, ice cream bar). Most fine dining will average 30-35 euros.

For more detailed planning and preparation for the Camino Portuguese, visit our blog https://kalutang.net/porto/planning-your-camino/. Feel free to leave comments.

Dr. Michael Gonzalez is Director/Founder of the NVM & Narita Gonzalez Writers’ Workshop. He is also The Hinabi Project Executive Director and Adjunct Faculty at City College of San Francisco’s Philippine Studies Department.

More articles from Michael Gonzalez

For another Camino route to Santiago de Compostela: A Walk to the End of the Earth: The Camino de Santiago de Compostela Pilgrimage — Positively Filipino | Online Magazine for Filipinos in the Diaspora