Barotac Nuevo, Where Football Is King

/Instead of the usual plaza, the St. Anthony de Padua church of Barotac Nuevo faces a football field. (Source: Smile Magazine/Cebu Pacific • Photo by Jilson Tiu)

Obscure and hardly prosperous, Barotac Nuevo in Iloilo province is nonetheless sticking to its reputation of being “the football capital of the Philippines” – an outlier in a country that is basketball crazy. Here, people live for football. Sons are groomed to be players, neighbors shell out money to help the teams, and the game is so much more revered than a religious fiesta that boys would climb the belfry to watch games at the height of the football season in the scorching heat of summer.

The townspeople watching the Barotac Nuevo Football Festival 2022 (Photo by Basisto Braga John Balladares/FB)

The Barotac Nuevo Football Festival 2022 (Photo by Basisto Braga John Balladares/FB)

The sport was introduced to Barotac Nuevo by the Monfort brothers whose family were originally French, when Iloilo province was a major trading port for textiles and sugar exports. The frenzy began in the 1920s, perhaps owing to the international success of football legend Paulino Alcantara, a half-Filipino, half-Spanish boy raised in Iloilo who scored goals for Barcelona surpassed only recently by the Argentine footballer Lionel Messi. The allure of Barotac Nuevo’s dream sport remains, although the town has fallen into hard times since the sugar mill it depended on closed and political governance degenerated.

The family keeping the sport running is that of the late martial law-era Mayor Mariano Araneta, whose sons, now senior citizens, sat together one morning in June during the town fiesta, after a Mass followed by playoffs at the football field, which the police sealed off from traffic. They were seated in the shade of a mango tree in their front yard, where food and liquor were passed around and guests played mahjong, which in the past collected earnings for grants to the football kids. Family members recalled their youth, when their father leveled the field and made it the town’s centerpiece.

“It’s a way of life for us,” said Pablito Araneta, the eldest of the sons, “and if you talk football, you’re good.” Football mothers, he remembered, could predict the future of their sons before they were born, saying the hard kicks inside their belly were a sign from God. Everything revolved around football, and every kid played football, so much so that every street formed a team. The local game grew bigger and better and rose to national level, registering breakthroughs in the late 1970s.

Pablito was coach of the Barotac Nuevo team, after he returned to the fold (with the help of his father) from the communist underground movement. He went back to the essence of his boyhood, and football saved him from emotional doldrums. In 1979 his team won the National Football Cup, the first outsider to beat the Manila team, the reigning champion. Three years prior, five boys from the town, including Pablito’s younger brothers, were chosen to play in China for exhibition matches, a trip they considered memorable because it coincided with the death of Mao Zedong.

The Araneta brothers (L-R) Pablito, Antonio and Mariano (Nonong)

Pablito was just in his 20s, already having borne the trauma of fighting in the jungle to overthrow the martial rule of President Ferdinand Marcos. He was nearly killed in an internal purge before he surrendered. It was so shocking that someone of his family stature had defied the status quo. Not only was his father the town mayor, their family name is linked to a vast, influential clan that controlled the region’s sugar plantations. Pablito returned as the prodigal son who picked up the pieces of his life by playing football.

It would have been more politically astute of the mayor had he trained his son to replace him, to build a mini-dynasty so common in provincial fiefdoms where politics is the business of the day. But football was so loved, so rooted that it was impossible to resist. The senior Araneta himself was a football player who started the leagues in his time and built the football field as if it were a shrine for his constituents.

The family is related to the wife of current Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos Jr., son of the ousted dictator. Ironically, this particular Araneta family supported Team Leni Robredo, the vice president who was Marcos’ strongest opponent in the elections last May. The clan went against the choice of the current mayor who pushed the townspeople to support Marcos.

The second Araneta son, Antonio, went on to play with the national team and was later hired by a football club in Germany. He lived in the town of Pforzheim for about a decade before returning home to retire and start his own family business in Iloilo City.

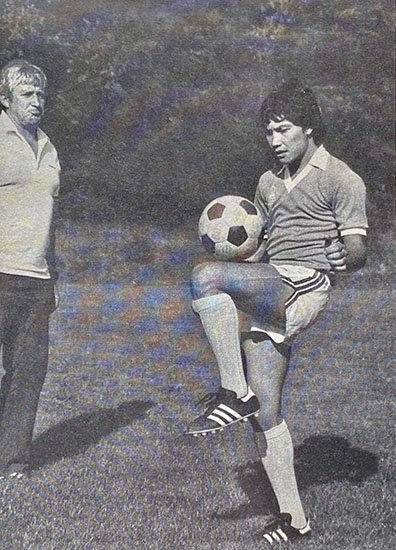

Antonio Araneta in the ‘70s

“We are a football family,” Antonio said, “and the town is our family.” The third son, Mariano Jr., was also on the national team and is now president of the Philippine Football Federation (PFF). He proudly says, “A small-town team can compete with the best.”

Their heyday may have come and gone, but there is no doubt that a player from Barotac Nuevo is still an added power to any team. Even the Army, Navy, and Air Force recruit from the lot to boost their teams for national games. For the boys of Barotac Nuevo, the sport has become a way out of poverty, a chance to obtain university scholarships. Perhaps one day another Paulino Alcantara would rise from among them.

Another football field has been built, away from the plaza, hidden somewhere in the rice fields, with a training center and a small dormitory built with money donated by the worldwide Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA). The Philippines received a million dollars every four years, according to Pablito, when he was secretary general of the Philippine federation. That’s not quite enough to cover staff salaries, grassroots training, youths programs, and competitions that could run up to 1.5 million pesos each.

Under the blazing heat of the sun, with the monsoon delayed, boys under 19 years old played against the bigger boys of the Air Force team. Townsfolk gradually filled the edges of the field, squatting on the ground in the absence of bleachers, while Adele’s “Hello” played through the mega-stereo speakers at half time. Watching them play, Pablito figured that the opportunity to give football in the Philippines a hard kick to prominence had been sadly missed.

“Why football?” he asked.

“Because of our size,” he said, answering his own question. The size of Diego Maradona, for example, and definitely not the size for basketball. “And not only that: we’re very good dancers, we have good motor skills.” As graceful as, say, Zenadine Zidane when he scored his way to World Cup victory in 1998, moving across the field like a ballet dancer.

For Filipino football players, reaching the World Cup is like trying to touch the moon. The national team is usually eliminated from the get-go. The team self-deprecatingly calls itself “Azkals,” the Tagalog diminutive for street dogs that forage for food scraps. Football has not grown as fast as it should have over the years. It’s not as popular and bankable as basketball, considered the national sport inherited from the American colonial years.

Mariano “ Nonong” Araneta, Jr., PFF President, with the Azkals coaching staff and players during the 2019 Southeast Asian Games in Manila.

Philippine football can kick for a higher status as football is gaining recognition in Asia. Indeed, the Azkals had their hurrah moment in 2010 when, in “the miracle in Hanoi,” the team beat Vietnam in the ASEAN championship. Six of the players were from Barotac Nuevo. Now, the national team brings in players of mixed Filipino heritage who were born abroad and trained there in their formative years, a move which Pablito said is a “shortcut” to bolster the prowess of the local boys.

“We don’t have sensational players,” his brother, Antonio, lamented. The sport has failed to rouse the entire country, unlike basketball, pick-up games of which can take place in any corner of the country, from tight neighborhood streets to country farm roads.

“Football is an intelligent game,” Marciano Jr. mused, “it requires a higher level of appreciation.” But Filipinos, he said, prefer a quick goal as they see in basketball, “not the slow exciting buildup of the football game.”

Still, the Araneta brothers hope to give football a second wind. Pablito, now 73, is a sports consultant to the governor of Iloilo, creating marketing plans for a football program that is timely for the tourist boom and environmental transformation efforts in the province. His younger brother, serving with the national football federation, has put in most of FIFA’s donation to the building of a training center outside of Manila, replicating what his father had done on a bigger scale.

In Barotac Nuevo, childhood football memories of everyone from civil servants to market vendors keep the sport alive and kicking.

Criselda Yabes is a writer and journalist based in Manila. Her most recent books include Crying Mountain (Penguin SEA) on the 1970s rebellion in Mindanao and Broken Islands (Ateneo de Manila University Press) set in the Visayas in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan.

More articles from Criselda Yabes