Ballesteros on My Mind

/The small town became the center of my universe until I was nine. We lived in the sentro (town center), where electricity was available only for a few hours each night. We didn’t have a TV set or a telephone, but we did have the luxury of owning a radio. It was an amazing toy because we could hear broadcasts from as far away as Taiwan and China. Ballesteros also had one movie house that showed a Tagalog film twice or thrice a week.

The People's Park and the town hall in Ballesteros, Cagayan. (Photo courtesy of Merlita Usita Campañano)

While agriculture was the town’s main industry, fishing was also big since Ballesteros is on the coast of South China Sea. The sea was the town’s main attraction: We went on picnics on the beach, strolled on the sand, or watched the sunset. We children would help the fishers haul in their huge nets, and would be rewarded with a handful share of their catch of the day.

When the tides ebbed, a small shellfish called gakka, would be left in the sand. Gakka is a culinary delight endemic to few coastal towns of Cagayan. Fishers would wade into the waist-deep seawater and scoop the gakka out of the sand, using a basket with a bamboo handle called taku.

Gakka (Photo by Merlita T. Bayuga)

Cooking the gakka was simple. Boiling water was poured over the gakka and immediately drained. Then, the shells were ready to be opened.

The sea in Ballesteros was also the source of local myths and legends. Grandaunt Inding told us stories about a mermaid that would appear to one good-looking guy in town. But the sea was also feared by the townspeople. The children were discouraged from swimming because at least one person drowned every year.

There was, however, no escaping the presence of the sea in our lives. At night as I lay in bed, I could hear the sound of the waves, lulling me to sleep.

Small Town Life

Being a small town, the layout of Ballesteros was easy to figure out. There were three schools in the sentro. The two private high schools were on the opposite ends of the sentro, whereas the public elementary school was on the far north toward the sea. The marketplace, bandstand, municipal hall, open-are auditorium, tennis court and Roman Catholic church were within walking distance of each other.

There were few motor vehicles. Generally, people in Ballesteros at the time walked to their destination. Or one could take a kalesa, a two-wheeled horse-drawn carriage. The trip was usually slow, which was fine with me because I loved observing people and houses along the way.

Some of the houses caught my attention, especially those with signs on their facades. The signs advertised the professions of the residents, in some cases, even if they no longer lived in those houses. Ballesteros professionals then were limited to three types: medical doctors, attorneys-at-law, and certified public accountants.

The townspeople of Ballesteros knew how to have irreverent fun. The town honored the dead on All Saints’ Day. At 12 midnight of November 1st, people guarded their material possessions because “spirits” might steal them. The next day, the stolen stuff, such as ladders, crosses from the cemeteries, and large earthen jars called burnay, would appear at a street corner, where the burglary victims could get them back. Although they were not pleased, the owners did not complain because the “crime” was a tradition.

Our family stayed with Grandaunt Inding in a nipa-roofed house that was built in the ‘40s. We knew this because the date of construction was painted on one of the beams. My mother would talk about her own family’s house that was located in the same lot but near the commercial street of Ballesteros. It was burned down during World War II.

From Grandaunt Inding’s house, which was a few steps away from one of the private high schools, we could hear a teacher giving a lecture or students booing their classmates. Grandaunt Inding would mutter to me, “Those are disrespectful students. I hope you and your siblings would go to a better high school in Manila.”

From the window, I would watch the high-school students pass by. I noticed everything about them and would not hesitate to give our a comment. My mother described me as a “prying” child, even at age four or five. For example, when I saw a boy and a girl walking together, I would holler to the girl in Ilocano. “Manang (an appellation for an older sister or female), is he your boyfriend?” The girl would usually say, “No, ading (an appellation for a younger person), we’re just friends.”

The high-school students did their physical-education exercises in the street. I would watch them while sitting on gigantic logs, which were, I later learned, the horrifying results of deforestation. Back then, however, my playmates and I had fun climbing up the logs and feeling like we were on top of the world.

My mother was a hardworking woman, She was a nurse at the National Orthopedic Hospital in Mandaluyong, a suburb of Manila. In Ballesteros, she was a homemaker and a self-employed entrepreneur. She did other women’s hair, raised turkeys, and had a thriving business selling potted bougainvilleas from our garden.

In the early ‘60s, the market days in Ballesteros were Thursdays and Sundays. I would sometimes accompany my mother when she went to the market. It wasn’t always fun because she wouldn’t buy my fantasies on having oodles of toys. She always emphasized that our family should live within our means, a veritable example of the Ilocano people’s trait of thriftiness. I was therefore forced to be resourceful.

Video follows: The Ballesteros of Cagayan, video edited by Ivan Kevin Castro

Lilang Polda

In the late afternoon, I would stand at the bandstand and watch every westbound kalesa. Often, my favorite character would appear: my father’s mother, Lilang (Grandma) Polda, in her traditional regalia—the tapungor, a bandana for covering hair, and the native loose blouse called kimona that went with a pandiling, a long skirt. Extending my right hand with an open palm very much like a beggar, I would greet her, “Lilang! Lilang! Lilang!” She would smile, “Ay, apokok! (Oh, my grandson!) and reach into her bosom and voila!—out came a knotted hanky that she would untie, filled with cold cash. I thought she was a walking bank, if not the richest person on earth. She would give me coins—plenty of them! I would thank her profusely and speed away. I couldn’t wait to spend my loot.

Lilang Polda (Photo courtesy of Rey E. de la Cruz)

Lilang Polda was widowed early and worked hard to raise her children. A woman ahead of her time, she traveled to and from Ballesteros and her original hometown, Magsingal, Ilocos Sur, to trade rice, vinegar and bagoong (fish paste).

I hijacked Lilang Polda quite frequently. Bless her, not once did she mention our financial transactions to my mother. The entrepreneur in her must have recognized my independent streak early on. She provided me with the capital for being true to myself, for trying my best and collecting and enjoying experiences.

While Lilang Polda gave me the opportunity to be a self-starter, it was from reading that I learned about a collective experience. Each Thursday afternoon, the Philippine Rabbit bus from Manila would arrive in Ballesteros. The driver would deliver copies of the weekly magazine, Bannawag (Dawn), to Nang (short for nanang, an address for mother or a female adult) Dolly’s store. The magazine covered a myriad of topics, and included feature stories and serialized comics. But it was its literary section that people, including children, looked forward to and talked about. Reading the short stories and serialized novels was a shared experience that people enjoyed. I remember guessing with my playmates what the characters would do or what events would occur next. My cousin Manang Felicing made our family proud when she placed first in Bannawag’s short-story contest. I don’t remember what the story was about, but it must have been about a romance because the illustration showed a man and a woman standing and looking at each other.

My first job was to sell the newspaper Manila Bulletin on the streets. Granduncle Lope was the newspaper’s town distributor, and he recruited the neighborhood children as sellers. I was assigned a section of the town as my route. Holding a few copies of the newspaper, I would call out, “Bulletin! Bulletin! Bulletin! “ It would be twilight by the time I finished the job. Granduncle Lope paid us news carriers just a few centavos, but, boy, were they hard-earned!

Schoolboy

My memories of going to school in Ballesteros remain very vivid. Public elementary schooling in the Philippines went up only to sixth grade at that time. I went to the public elementary school in Ballesteros with the children of fishers and farmers, some of whom came to school barefoot. At the end of the day, we would help clean the classrooms and even pull out grasses in the field.

The elementary-school campus had several buildings. In the main building were the principal’s office, classrooms for second-and third-graders, and one class of first-graders. In a separate building were classrooms for the fifth-and sixth-graders and two classes of first-graders. Another building housed fourth-graders. A wooden house, where school guests would sometimes be billeted, was the home-economics building. There was an industrial-arts building, and the outhouses were nearby.

Because I started school in the first-grade class of Mrs. Palijo, I had always attended classes in the main building. When I was in third grade in the school year 1963-1964. I clearly remember that my classrooms were next to the office of Mrs. Pacis, the school principal. My third-grade teacher was Mrs. Unite. I knew that it would have been my last year in the main building because the fourth-graders were in a separate building. However, this was not to be.

A catastrophic event happened one pleasant day in January 1964. My father and eldest brother, Elmer, had just left Ballesteros after spending the holidays with us. By that time, Elmer was already attending high school in Manila. The schoolchildren in Ballesteros were still on holiday break. It was late afternoon when we heard shouts of “uram (fire)!” A billow of smoke could be seen from a distance. Word spread quickly that the main building of the elementary school was on fire. I ran toward the direction of my school. Embers were flying all over. I saw people climbing to the rooftops and dousing the nipa roofs of the houses with water. A crowd had gathered in front of the burning inferno. I had never seen such a big fire in my life! I was standing next to Mr. Adarme, a teacher, who was frantically composing a message to be telegraphed to Manila. It was a terrible day! The main building burnt to the ground right in front of my eyes.

The author's mother pinned him a ribbon at his school's closing ceremonies on April 17, 1964. (Photo courtesy of Rey E. de la Cruz)

Like most small towns in the Philippines, Ballesteros had no fire department. Nobody knew how the fire started. There were rumors that a gasoline tank was found on the scene, and that a disgruntled politician had masterminded it, for reasons that were not explained. All that mattered to us children was that the main building was gone, and we didn’t have classrooms.

Very quickly, classrooms were set up in various homes. My third-grade class used the second floor of a house near ours. We also used a space in the home-economics building. Our schooling was not interrupted at all.

The fire did not dampen the spirit of Ballesteros. Life went on as usual. At the end of every school year, the townspeople came together to celebrate academic excellence and gave honor students the star treatment during the schools’ closing ceremonies. The honor students’ names would be called, and their proud parents would come up to the stage and pin a ribbon on them. The audience would applaud, and some members of the audience would go onstage to present gifts to the honor students. When Manang Ciely, who was Mrs. Unite’s only daughter and a perennial gift giver, was graduated valedictorian in high school in 1964, she received a mountain of gifts.

My family left Ballesteros in 1964 and joined my father and brother Elmer in Quezon City. When I revisited in 1966, a new low-rise structure had replaced the main building of the elementary school. I missed the imposing main building, with its concrete steps and its huge sign that said “Ballesteros Central Elementary School.” My second-grade teacher, Miss Aquilizan, would let us practice reading by asking some of our classmates to go down the steps to the front of the building and read the name of the school aloud.

Much has changed since then. I traveled from Chicago and went back to Ballesteros for a few days in 2000 to attend a family reunion and the town fiesta. Grandaunt Inding’s house was gone. The marketplace had been moved closer to the seaside. I saw tricycles instead of the kalesa. The two private high schools were still around, but there was also a public high school. I went by the public elementary school one night on my way to a carnival, but I did not venture into the darkness to see how the campus looked like.

So many things have changed indeed, but my memories of Ballesteros will always be with me. Because Miss Aquilizan never called on me to read the school sign, I’m still waiting.

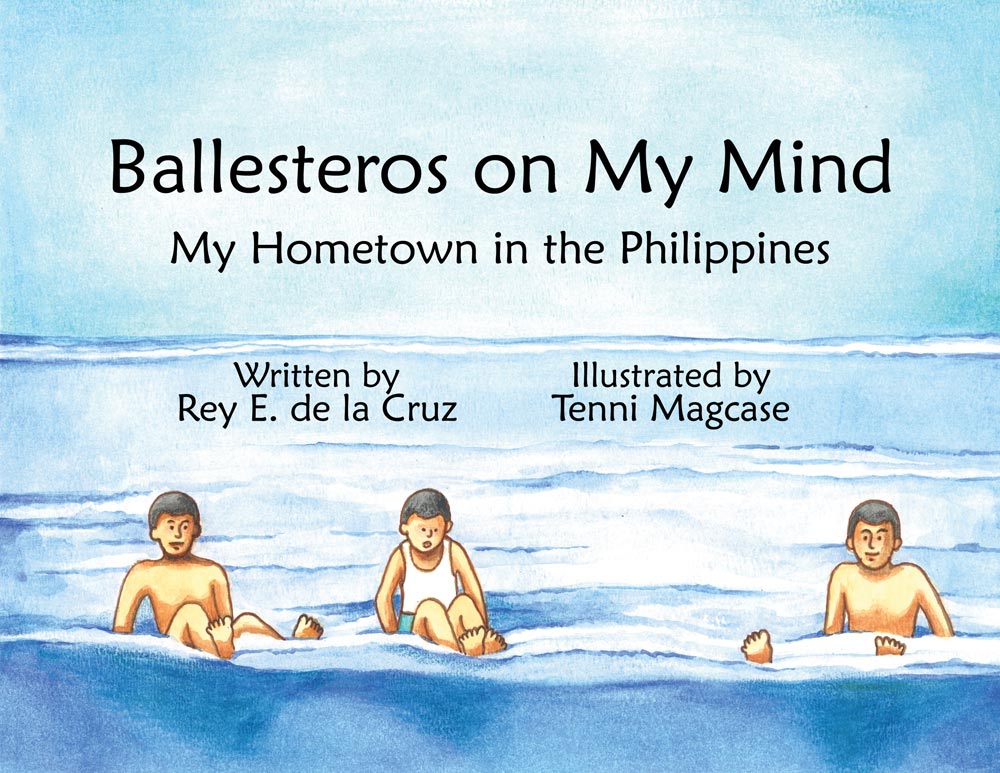

The book "Ballesteros on My Mind: My Hometown in the Philippines," Written by Rey E. de la Cruz and illustrated by Tenni Magcase.

The Positively Filipino article above was originally published in Filipinas, May 2008.

The author gratefully acknowledges the following for their assistance: Edna Baraoidan Catig, Jerry Clarito, William Fernandez, Penelope Flores, Ph.D., Daisy Garcia Fonacier, Angioline Loredo, Emilia Garcia Rulla, Clarissa Bañuelos Subagyo, Ben Umayam, and Pat Whitson-Kane.

To order the book, which is in English, Spanish, Tagalog, and Ilocano, please go to ballesteros.carayanpress.com or www.carayanpress.com.

Videos follow: "Ballesteros on My Mind" book trailers in English, Spanish, Tagalog and Ilocano

Rey E. de la Cruz, Ed.D., writes from Chicagoland when he is not loving the arts and traveling. He is the author of the children’s book, Ballesteros on My Mind: My Hometown in the Philippines, which also has Ilocano, Spanish, and Tagalog versions.

More articles from Rey E. de la Cruz