Art Star Manuel Ocampo’s Second Coming

/Manuel Ocampo at the press preview of First Look (Photo: © France Viana. Artwork: © Manuel Ocampo, courtesy of Asian Art Museum of San Francisco)

Best known for his Catholic Grand Guignol imagery, Ocampo once claimed to have learned his signature faux retablo style from a priest for counterfeiting purposes. Largely self-taught, he dazzled the art world with his precocity and virtuosity, leaping from a single one man show in Los Angeles in 1988 to rave reviews and participation at the Documenta and Venice and Whitney Biennials. He was awarded the Rome Prize in 1995 and a National Endowment for the Arts grant in 1996. Among his provocative subjects are ancient forms of crosses, including the swastika, a symbol that caused his expulsion from the main floor and relegation to the basement at Documenta IX in Kassel, Germany in 1992.

I first met Ocampo over 20 years ago, just before his meteoric rise, (“I was just a child then,” he remembers), and was curious to see how fame had changed him. He has lost most of his hair but none of his charm--in fact, he remains a paradox: his imagery is angry, often violent, but he is affable, even sweet. His paintings are narrative and materially visceral, yet are often inspired by conceptual and philosophical abstractions.

Manuel Ocampo's Artist Examining Life Closely (1998) (Artwork: © Manuel Ocampo. Source: easelkisser.com)

Ocampo’s surreal imagery begs explanation; he layers Spanish religious icons, American pop culture, local kitsch and obscure texts to illustrate Filipino post-colonial identity. The prospect of learning their true meanings from the artist himself drew a crowd to his lecture, held at the Museum on September 4, organized by educator for public programs Marc Mayer, and moderated by assistant curator of contemporary art, Dr. Karin Oen.

Manuel discusses his text-based work with Asian Art Museum’s assistant curator of contemporary art, Dr. Karin Oen. (Photo © France Viana. Artwork © Manuel Ocampo)

Ocampo did not disappoint, managing quite a few revelations in the hour-long conversation:

On his compositional style: “This is where I live. It’s a mess, which is why my paintings are a mess,” he claimed, starting the slide show with an aerial view of a massive Manila traffic jam, vehicles and people gridlocked in anarchy.

On his provocative subject matter: “I’m not afraid of controversy—in fact, I invite it,” he admitted, in response to a question on his intentions. “I’m saying, look at this, but don’t look at it, it’s just a painting, it is not real” —reminding the audience that his paintings are mere two-dimensional explorations, and no gods were actually harmed in the making of his art.

On his choice of medium. “I’ve always been a painter, it’s always been about how I can push painting further. I might ask people to pay attention to the pieces in ways other than conventional painting, but in the end I’m expanding the concept of what a painting is.” Ocampo was referring to his forays into installation, such as at a Los Angeles show where he stripped his paintings from their frames and laid them on the floor to be walked on, hanging one as a hammock.

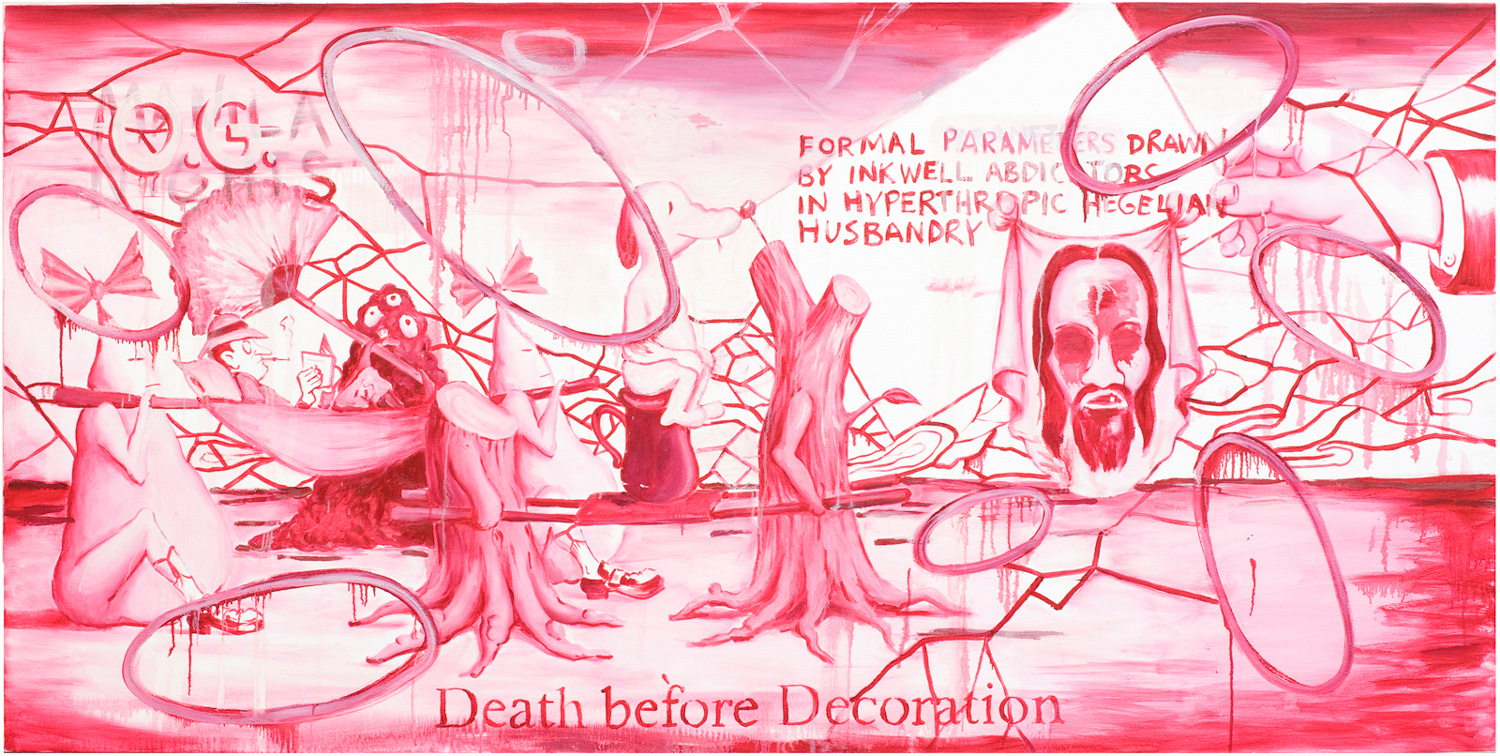

On sources of inspiration. He credits his first job drawing editorial cartoons for his mother’s newsletter with his love of incorporating text in his works. He finds material literally everywhere. A postcard with the cryptic text, “comprehensive only to a few initiates,” found on the floor, was appropriated in full for a text-only painting (2000-2001). Another text that sparked a work was conceptualist John Baldessari’s quote, “Everything is purged from this painting but art, no ideas have entered this work,” which he inscribed around a Duchampian toilet, overturned and spilling intestines, in his work, Artist Examining Life Closely (1998). The work currently on exhibit, An Object at the Limits of Language—Necromantic Kippian Emancipator: No. 2 was painted in response to the death of German artist Martin Kippenberger, whose absurdist humor Ocampo greatly admires.

Currently on exhibit at the Asian Art Museum: Manuel Ocampo, An Object at the Limits of Language—Necromantic Kippian Emancipator: No. 2, 2000. Gift of Malou Babilonia. (Artwork: © Manuel Ocampo. Photo: © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco)

On the persistence of Jesus imagery: “It’s not unlike Chinese painters who paint images of Mao,” he responded, to a query on why he compulsively paints Jesus images. Ocampo has two works in the Museum’s collection, the other one not on display. He showed a slide of the second work, whose blasphemous title is best not quoted (in fact, even Ocampo himself decided not to mention it: “I forgot the title,” he demurred). The canvas is peppered with dozens of disembodied Jesus heads swirling around a cloud-like orifice. He recalled a painting that hung in the middle of the sala of his childhood home, a Jesus portrait with eyes that followed him wherever he went, and fingered it as the origin of his obsessive-compulsive habit. “That image burned into my subconscious. Now, whenever I get stuck and don’t know what to do next, I paint a Jesus,” he confessed.

On his process. “It’s about my Catholic background. I don’t want to present my paintings as perfect because we don’t want to present ourselves as perfect,” Ocampo offered, when asked about why he “destroyed” his works, carefully painting images then overpainting, crossing out, or scarring them, creating distressed surfaces. He affirmed a theory proposed by several scholars that these are acts of self-flagellation. “I beat myself up, and that’s how I treat my paintings as well. I stress them.”

“‘This is where I live. It’s a mess, which is why my paintings are a mess,’ he claimed, starting the slide show with an aerial view of a massive Manila traffic jam.”

On the Manila art scene. “The auction houses are manipulating the market,” he complained, bemoaning the current trend of investors replacing art lovers as buyers. He said he missed the days of intimate openings, where artists were both exhibitors and their own audience. He disapprovingly recounted how conversations today center around artists recent auction results and little else. In response to the pricing out of the market of many “real collectors,” he opened a print gallery in 2011 called The Department of Avant Garde Cliches (DACG) to help keep art affordable and accessible.

On what’s next. Ocampo thinks he might continue to curate; he organized the Bastards of Misrepresentation exhibition, which opened in Germany in 2005 then traveled to Spain, U.S., and many other countries. He also has just began a new series of demon paintings (“more like Greek daimons, spirits who are fools, often drunk”).

I asked him how it felt moving back to Asia, after being in the thick of Western the art world, and if he felt further away from the center of the action. “Not at all,” he said, “it’s a very global art world now and with the Internet and telecommunications, an artist can be the center of it wherever he is.” As to the rest of his plans, he quotes Kippenberger, “Never give up before it’s too late.”

Manuel Ocampo's Boycotter of Beauty (2011) (Artwork: © Manuel Ocampo. Source: artsy.com)

First Look will run from Sept. 4 to Oct. 11, 2015 at the Asian Art Museum, 200 Larkin Street, San Francisco, CA 94102. The talk and exhibition are part of several Asian Art Museum events to celebrate Filipino culture and heritage. On Sept. 24, the museum opens Piña: An Enduring Philippine Fabric, an educational display focused on the rich tradition of Philippine weavings and textiles. The Museum will host a film screening of ‘‘An Open Door: Jewish Rescue in the Philippines,’’ on Oct.1, and will kick off the annual Filipino American History Month Celebration with daylong events on Oct.4, 2015.

France Viana is a journalist, visual artist and marketing consultant. She is an active board member of Philippine International Aid and the Center for Asian American Media, sponsors of the CAAM Asian American Film Festival.

More articles from France Viana