Antoon Postma and the Mangyan Legacy

/Antoon Postma (center) donating an ambahan collection to the U.S. Library of Congress (Photo courtesy of Mangyan Heritage Center).

Mindoro is one of the seven larger islands in the Philippines. It is where approximately 100,000 indigenous people collectively called Mangyan live. Among the Mangyan, there are seven distinct linguistic communities. The Hanunóo is the most written about and well known, because they practice an ancient pre-colonial craft of ideographic writing. Much of what we now know about them came from the scholarly work of Antoon Postma and Harold Conklin.

Antoon Postma, for over two decades, singlehandedly devoted his life to documenting the lives and culture of the Hanunóo Mangyan of Oriental Mindoro. He now joins other Mangyan ancestors as well as admirers of their culture, like my father, the late National Artist N.V.M. Gonzalez, and eminent anthropologist Harold Conklin. Body and soul have finally found each other. Antoon passed away after a difficult period of dementia. Antoon, fondly known as bapa (uncle) to the Hanunóo, was laid to rest on October 25 of this year, in Panaytayan, Oriental Mindoro where his family kept residence.

Antoon Postma, Dutch by nationality, came to Mindoro in 1958 as an SVD missionary, when the island was still notorious for its miasmic malarial airs, “bad folks,” and a dubious historical reputation promoted by Spanish and pre-World War II American colonial administrators. The most prominent among the colonials was Dean C. Worcester, the Secretary of the Interior of the American colonial government. Worcester was an effective propagandist for the idea that the Filipinos were too racially deficit to be self-governing.

Under the cloak of modern ethnographic tools, especially photography, Worcester went around the Philippines documenting the indigenous populations throughout the archipelago, including the Mangyan of Mindoro. His legacy was the creation of the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes as a separate jurisdiction from colonial government administration. Worcester had executive control over the Cordillera highland peoples: the Mangyan/Tagbanwa and the Mindanao indigenous people, except Moroland. He supported the popular racist thinking in the 19th century that white Anglo-Saxon civilization was the apex of human development and the African type (locally called Negrito in those times) as the lowest.

“Between the two of them, the scholars Postma and Conklin left a formidable legacy, a treasure, a baseline archive that puts the Hanunóo as one of the most unique cultures not only in the Philippines, but also among all indigenous peoples worldwide.”

Worcester’s ideology followed Rudyard Kipling’s famous “white man’s burden” concept of development where Anglo-Saxon nations had an obligation to uplift the lower races who were yet incapable of self-rule. Ironically, most of the countries populated by the “lower races” were colonies of European powers, including the Philippines, America’s newly acquired territory in 1899.

In 1906 Worcester documented and photographed the Mangyan. He described them as decidedly “wild,” “ludicrous” and “lazy.” Worcester observed that they lived in clean, decent houses and had a childlike innocence because the Mangyan invariably withdrew to the interior at the sight of lowlanders and, therefore, had not been contaminated by lowland culture. Worcester acknowledged that the Mangyan had a form of writing, although this fact did not seem to fit his agenda of deprecating Filipino culture and highlighting the civilizing effects of American rule.

Unfortunately, this was the image of Mindoro perpetuated by the American-inspired public school system that lingered in my imagination during my childhood years. It was not until my parents allowed me to travel to Mindoro on my own, that the foreboding image of Mindoro eventually dissipated. Much of the work of changing the image of Mindoro was done by Antoon Postma. During the summers I spent on my grandmother's farm near the Hanunoo homeland, I often anticipated an occasional meeting with kind and gentle Mangyan who would pass through the farm on their way to their hillside homes.

Unfortunately, I never got to meet Antoon in person. I had hoped to see him in 2017 on my next trip to Mindoro. We corresponded a bit when I was doing my graduate work in anthropology. He also sent me a draft of the Surat Mangyan handbook that he was preparing at the time. I knew about him about primarily through my father who held Antoon in very high regard as the bastion and keeper of Mangyan culture that was being threatened by the onslaught of vested interests in the Mangyan highlands. Until the 1970s, N.V.M. Gonzalez’s Mindoro, the island of migrant frontiersmen and women who eked out a living in the ash-covered loam of Oriental Mindoro, was becoming a no man's land. The Mangyan, the islands’ original inhabitants, were being pushed further up into the interior highland. Land grabbing was rife and mining interests eyed the highland’s rare minerals with a greed matched only by the indifference of local government bureaucrats. N.V.M. Gonzalez described his relationship with the Hanunóo in his major essay on literary criticism, Kalutang:

“It is said among the Hanunóos the body and soul are not readily separated… I have lived among the Hanunóos; I grew up among them. I have watched them walk down the jungle trail, interminably making song with two wooden sticks. The song helps the soul know where the body is…” (Kalutang, 1995). In his 1941 novel, The Winds of April, N.V.M. Gonzalez depicts the shared struggle of both the Mangyan and the swidden farmers as they battle two-legged pestilence and the dangers of forest life.

Antoon Postma, then an SVD missionary, seized on the urgency of the moment and became the archivist and promoter of the culture of the Hanunóo, who to this day continue to use the only living syllabary of pre-colonial writing in the Philippines. Surat Mangyan as it came to be known, gives evidence that precolonial inhabitants were not illiterate Indios as inscribed in colonial histories. Both baybayin and the Laguna copperplate inscription show that early Filipinos were equipped with indigenous literacy well into the early 17th century. In fact, Antoon Postma is credited with deciphering the mysterious script writing on the Laguna copperplate, one of the most important archeological finds in Philippine history. His long study of the surat mangyan gave him an advantage.

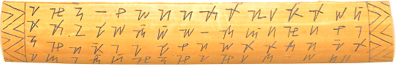

Along with surat mangyan came the exquisite art of the Hanunóo ambahan, a unique genre of extemporaneous verse that the Hanunóo recorded by writing on leaves or bamboo strips and tubes. Most were usually love messages from a suitor delivered by a traveler who might be headed towards the maiden’s village. Postma was instrumental in recognizing the ambahan heritage as a part of Filipino indigenous oral and written literature. To assist in popularizing the Mangyan heritage, he inspired the establishment of the Mangyan Heritage Center based in Calapan, Oriental Mindoro to provide information, research materials and Mangyan crafts to the public. I am particularly fond of my bamboo bookmark, which is inscribed with a surat Mangyan poem translated by Postma:

In his correspondence, Antoon explained to me how important his scholarly work was in keeping Mangyan culture viable.

my sweetheart. so nice and fair write it on the bamboo tall

we have now agreed all right and wherever we will meet

just now at this hour of night on a trail or on a street

have it written on the wall in a hut or in a house

one day I will be your spouse

“Studies on the culture of the Mangyans, and publishing them I believe to be important. Not only to provide a better understanding about the Mangyans but also for the young Mangyans themselves, who tend to be forgetting their own culture and literature, because little attention is paid to this in the elementary schools. ” Antoon added that at least in the only functioning local high school, Mangyan culture was part of the curriculum (personal correspondence, 1991).

Antoon left the SVD order and eventually married Yam-ay Insik in 1989 with whom he had four children -- Anya, Ambay, Yangan and Sagangsang.

The author with Anya Postma, Calapan, Oriental Mindoro (Photo courtesy of Dr. Michael Gonzalez)

I met Anya when she conducted a Mangyan awareness outreach for our writers’ workshop in Calapan, Oriental Mindoro in January 2016. Anya is the face and voice of the Mangyan Heritage Center in Calapan, which serves as a library and heritage museum/shop. Anya’s lecture is comprehensive, and she gives you an intimate knowledge of Mangyan culture in a one-hour package. Anya serves her people well and is busy promoting Mangyan culture around the Philippines. It might have been premature then, but I wished the Mangyan had someone like Anya when I was in college. To hear Anya deliver her Mangyan awareness lecture would make any Mangyan proud.

Lynette Postma, Antoon’s daughter-in-law, is married to Antoon’s son Sagangsang. In the last elections Lynette won as vice-mayor of Mansalay, a political office that can become a strategic platform as the Mangyan face daunting issues of land management, mining instructions and continuing pockets of poverty compounded by poor health services. Mangyan who usually avoid travel beyond the waters of Mindoro are now tapping into the informal urban labor market as a source of additional income. Ironically, Mindoro is now among of the most prosperous provinces that report actual revenues to the national treasury; it is considered the rice granary of Greater Manila. The provincial government has ambitious plans that include a railroad that would link the western and eastern coasts of the island.

On the other side of the Pacific Ocean, in the U.S. this same year around May, Harold (“Hal”) Conklin, passed away. A colleague and dear friend of Antoon Postma who started his career as an anthropologist in 1947 after having first seen Mangyan culture as a G.I. during the WWII. Conklin returned to complete his Ph.D. and produced original research that provided a most detailed description of Hanunóo culture besides those of Postma’s. Much of Conklin’s extensive collection of Mangyan sound recordings and observations are held in the Smithsonian and Yale archives. Conklin documented in fine detail how the Hanunóo, whose outside appearance spoke of simple beauty, actually have an extensive vocabulary for plant species and have a sensitive understanding of land management and a complicated knowledge “color” categories of “lightness, darkness, wetness and dryness” and differences in-between (think of “shades of light and dark”). Conklin’s research, together with the 20,000 audio recordings of ambahan poems donated by Postma to the U.S. Library of Congress, immortalize Mangyan knowledge. These indigenous knowledge is a far cry from Worcester’s imaginary “other” and the lowlander use of “Mangyan ka” to mean “you’re ignorant.

Between the two of them, the scholars Postma and Conklin left a formidable legacy, a treasure, a baseline archive that puts the Hanunóo as one of the most unique cultures not only in the Philippines, but also among all indigenous peoples worldwide. Their works show how one culture has negotiated its journey from precolonial to contemporary times amidst prejudice and government neglect. Through the works of these true scholars, Worcester’s image of Mindoro is reversed. What we behold is a culture that is at once literate and cognitively sophisticated, strong and ready to meet the new century with remarkable highland forbearance.

Dr. Michael Gonzalez has degrees in History, Anthropology, and Education. A professor at City College San Francisco, he teaches a popular course on Philippine History Thru Film. He also directs the NVM Gonzalez Writers' Workshop in California.

More articles from Dr. Michael Gonzalez