Adobo

/My mother did cook Filipino food, but I found it stinky (bagoong) or bitter (ampalaya) or scary (fish with terrified eyes staring up from a plate, steam rising from its body)… except for adobo and pancit and sticky brown rice with coconut.

It was California, so there were always plenty of vegetables and fruits, and I didn’t think our habit of eating them every day was particularly Filipino. I know now that it was. I think if my mother had let me eat with my hands, I’d have eaten a lot more rice. But, I was American, so that was out of the question.

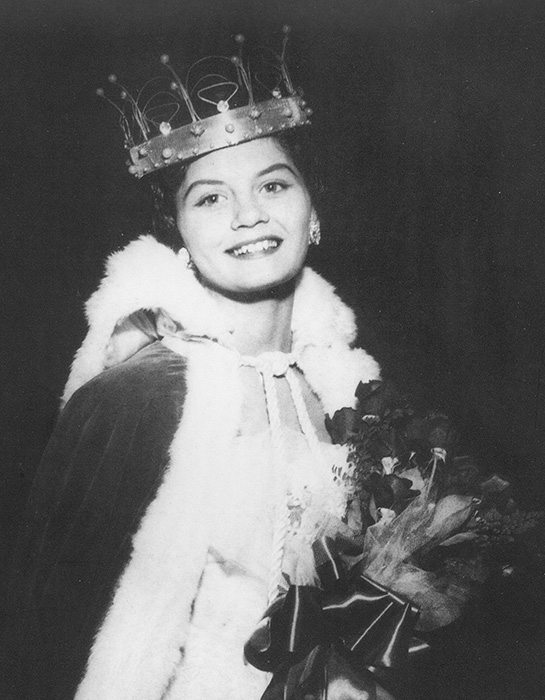

Carlene Sobrino Bonnivier, Homecoming Queen. Fall, 1956, when she was 16. (Photo courtesy of Carlene Sobrino Bonnivier).

Here’s what happened, though. When I was 17 and a senior in high school, I became engaged to a young man who, as time passed, revealed his very bad temper. One night, after a party he went into a jealous rage and threatened me with a gun. Two weeks later, the day after I graduated from high school, I sent a telegram to my Aunt Carmen, telling her I was taking a plane to Washington, DC, and would be arriving the next morning. I had only met my Aunt once when I was about 10 years old, and she’d come to the house with her sister, my Aunt Mary. They were in Los Angeles to pick up their half-sister who, they told me, was my first cousin and who was arriving from the Philippines the next day. As every Filipino I’d ever known was an auntie, an uncle, or a cousin, I wondered why they went out of their way to explain that to me. Later I learned that the cousin arriving in Los Angeles was the daughter of my mother’s sister. A real cousin. At ten, though, I didn’t deal in such hard scientific facts.

My aunties and my mother, with my sister and me chiming in from time to time, talked about the war and about all that had happened since they’d seen each other in Baguio. Aunt Carmen had lost her husband and almost all of the adult men in the family. Her husband had survived the March from Bataan but died in a Japanese prison camp. She’d lost her daughter, killed in her hands by shrapnel, a loss she could barely speak of. Now it was hard for her to play the piano because her hand was disfigured; but still, she did play. Aunt Mary had one leg that would not bend after she’d been operated on to save her leg, which had also been pierced by shrapnel. We sat in the living room quietly crying at the war stories and then laughing at other stories, some of them sad but funny anyway, others outrageously embarrassing and, we thought, hilarious. It felt wonderful to be with them, as if I had known them all my life. Maybe some day, they said, I could come and visit them.

“I was only 17, but that scene at the airport was indelibly imprinted in my heart as the day I understood what it was to be Filipino.”

Well, the day had definitely come. I left Los Angeles without telling anyone except my mother and sister where I was going. Looking back, I can see that I had probably wanted to marry so young because I wanted to have a family of my own, having grown up not fitting in really with the white kids at school but not being totally accepted by the African-American or Mexican kids either. There were Filipinos in the neighborhood there on Temple Street, near Figueroa, but they were mostly “the boys” from the Islands, and they weren’t allowed to marry Caucasians, so there weren’t any Filipino-American kids there except for me.

My father’s family more or less forgot about us after my American aunt had failed to get custody of my sister and me through the courts. Now and then, though, we’d visit my grandfather, or one of the uncles would come to the house. But it never felt to me that I was truly related to them. It wasn’t just the infrequency with which we saw each other. It was their manner: stiff and formal and awkward.

As the plane landed in DC, I looked out the window, wondering if Aunt Carmen had received the telegram, wondering if she’d actually come to the airport for me. I had her telephone number, so I could call and find out how to get to her house if she was okay about my coming out there.

In those days, we walked from the plane to the terminal. I remember feeling a terrible pressure in the air. It was humidity. Something I’d never felt before, and it added to my anxiety, my feeling of once again being somewhere I didn’t quite belong, maybe this time, really lost. But, when I passed through the gate, I saw my Aunt Carmen and at least 10 other people, young and old, waiting for me. They were all there at the airport just to welcome me, someone most of them had never even seen before. I was only 17, but that scene at the airport was indelibly imprinted in my heart as the day I understood what it was to be Filipino.

Aunt Carmen (left) came to visit the author when she was studying at the University of Valencia in the Summer of 1970. (Photo courtesy of Carlene Sobrino Bonnivier)

Aunt Carmen was not a blood relative. My mother had been a playmate of my Aunt Mary and Aunt Carmen when they were children in Baguio. Most of the cousins at the airport weren’t my blood relatives either. But I had never before in my life experienced a stronger feeling of family.

When we got to the house—where they hoped I would stay forever—there was meat and potatoes in case I didn’t eat Filipino food, and there was rice and adobo if I wanted some. Well, you know what I ate, and you know what I learned how to cook.

My best friend (who is Filipino from the Philippines) tells me my adobo tastes like it’s cooked in a clay pot because it’s so juicy and has exactly the right flavor and stickiness to it. What makes it so? The love I feel when I cook it, and that of course came from the love I received from people who did not hesitate to accept me, who let me be myself, who seemed to have naturally rushed to provide me with the family I had longed for all my life, who ate dinner together almost every night and who taught me how to cook.

Originally published in A Taste of Home by Anvil, Manila 2008.

Conceived in Baguio, Carlene Sobrino Bonnivier was born and grew up in the multi-cultural world of downtown Los Angeles thinking, as a child, that she was half American and half Catholic. When she was 15 she almost went to Juvenile Hall, but decided on a better course, and since then has trekked in the Himalayas, worked in the White House Press Office, published three novels, and edited the anthology Filipinotown: Voices from Los Angeles (1900 to 2014) which came out almost exactly a year ago.