A Palawán Artist Finds His True Self in Amsterdam

/Kanakan in his element, in his home (Photo from the collection of Kanakan Balintagos)

Even then, Auraeus was already a personification of inspired genius. His first play under the UP Tropa aegis, Walang Kawala, a Rogelio Sicat translation of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Huis Clos or No Exit was a tour de force on a raked stage, with costumes and makeup (by another celebrated Filipino theater artist: 2016 Tony Award-winning costume designer, Clint Ramos) and set design in stark black and white, underpinned by an art nouveau aesthetic.

From that point on, it was standard to expect that a Solito production, whether on stage or on the silver screen, was going to be unusual, thought-provoking, and a thing of beauty, as defined by classic Greek philosophers. No surprise there, considering that Kanakan Balintagos, the name by which Auraeus now goes by as an artist, is a graduate of Philippine Science High School. (Kanakan shared these links, http://bit.ly/2irsD7P and http://bit.ly/2htUKov, to explain his name change. He comes from a lineage of Palawán shaman chieftains. One day, a shaman uncle had dreamed of Kanakan’s true spirit name and shared it with him. When that uncle died, Kanakan decided to honor him by assuming his own tribal name, which means “Hunter of Truth.”)

“Kanakan may appear to be a citizen of the world, but he is first and foremost a Palawán, advocating for the various concerns threatening his people and home.”

In his works, Kanakan presents balance and symmetry in an otherwise chaotic human condition—a true marriage of art and science. In spite of his Pisay (the endearing and enduring nickname of the national science high school) background, he still went on to study Theater Arts at the state university. Theater remains his first love and cinema, his second. Of the many identities he can assume, he especially values his indigenous Palawán blood. He is the first Palawán to be born and raised in the national capital Manila. To appreciate the totality of Kanakan’s body of creative work is to appreciate the culture and society of his people.

Much has already been posted online and written in print about Kanakan. A cursory Google search of both his tribal and legal names alone yields over 60,000 results. Do that with each of his film titles and you get an exponential sum. After all, he is a prime mover whose every obra maestra elicits self-expression from other human beings, who are quick to talk about his creations. What else was there to add to that mass of literature about him? I decided to take a different tack.

Part of understanding Kanakan and his growth as a director and a writer is to see him within the context of some of the journeys he has taken to different parts of the world, where he had had opportunities to hone his craft further. One of his longer periods abroad was spent in the Netherlands and I sought him out to know more about that particular experience.

Kanakan’s one-year sojourn in the Dutch nation was to participate in a Screenplay Development Program at the Binger Filmlab in Amsterdam, in 2009, where he was in august company. One of the participants in the course was Jennifer Kent, director of The Babadook, an Australian-Canadian psychological horror hit, which she was just then developing in their class that year. They came under the mentorship of screenwriting professionals from across Europe and they provided a diverse experience for Kanakan.

The Binger Filmlab screenwriting class of Kanakan Balintagos (Photo from the collection of Kanakan Balintagos)

“Some were progressive; some were very classic, while there was one whose ‘mind was closed’,” Kanakan described the scenario in his class. “Many appreciated my indigenous world and inspired the truths in my work. They never saw it as exotic but as beautiful and something new. The one who couldn’t get into the universe I was creating told me to my face that my script was incomprehensible.” In the end, Kanakan did not even have to defend himself. Kent was quick to express her support for his writing and to accuse that mentor of being culturally insensitive.

His takeaway from that year of learning and creating was a clearer perception of himself. “I saw myself more, the strength of my Palawán identity. The weakness was not my work or in my work but in the narrow-mindedness of other people. It solidified my creative uniqueness.” And it was from those 12 months that his Palawán Trilogy was born: Busong, Baybayin, and Sumbang.

The first two films in the three-part series had already been made into critically acclaimed productions. Busong (Palawan Fate) starred Alessandra da Rossi and was part of the 2011 Cinemalaya Film Festival, where Kanakan won the Best Director award. In the same year, his dream came true when Busong was selected to take part in the prestigious Cannes Directors’ Fortnight. Busong tells the story of a young woman born with open sores and an inability to walk. Her brother carries her around in a hammock, looking for a healer and meeting helpful strangers along the way.

Kanakan stands atop a jeep with his crew, while directing a scene from Busong. (Photo by Karla Pambid)

Shooting the final metamorphosis scene of Busong, when Punay's (the lead character) wounds turn into butterflies. (Photo by Viory Schellekens)

Baybayin (Palawan Script), on the other hand, had Alessandra and her older sister, Assunta da Rossi, as the lead characters. They played half-sisters who fall in love with the same deaf-mute man. Without any other means of communicating with him, they both learn the Surat Inaborlan, the Palawán script, in order to express their desires for him.

Kanakan sets a scene for Baybayin with his three lead characters played by Alessandra da Rossi, Assunta da Rossi, and Adrian Sebastian. (Photo by Don Gordon Bell)

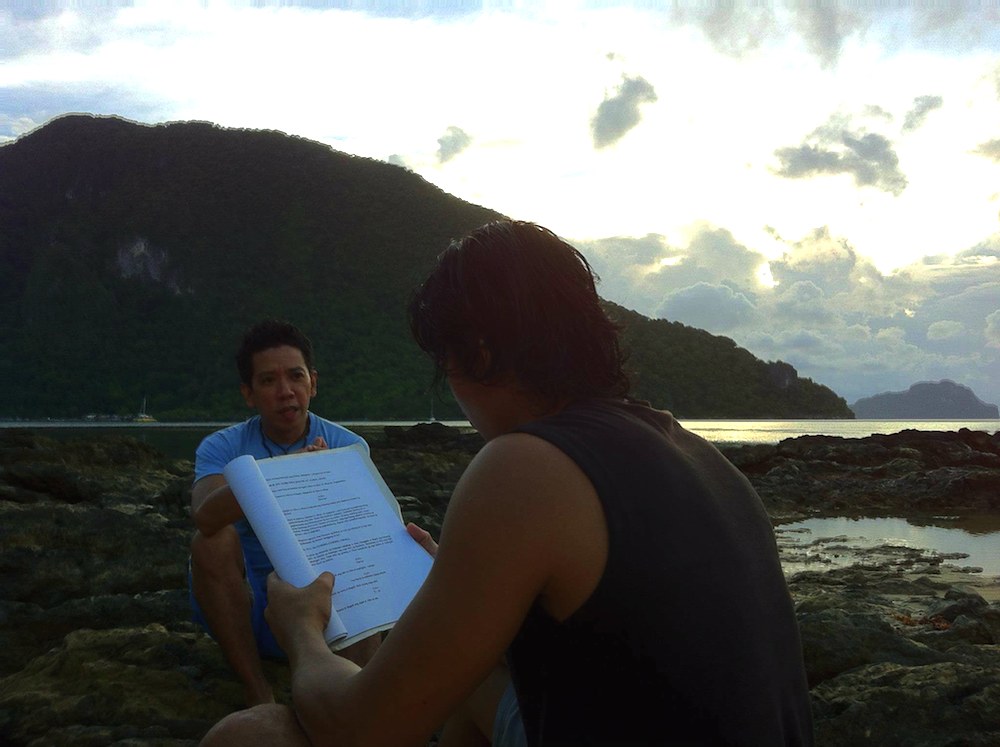

All in a day’s work, reading the Baybayin screenplay with a grand Palawan scape as backdrop (Photo by Don Gordon Bell)

And now, the journey that began in Amsterdam comes back full circle with the completion of the third part of the trilogy. Early in 2017, Kanakan was able to finalize the Sumbang script, as part of the Ricky Lee Screenwriting Workshop, Batch 15. It captures the mythical shamanistic history of the Palawán.

When I asked Kanakan which movie closely resembled his experience in the Netherlands, he replied, “Perhaps a Dutch Lost in Translation,” referring to the Sofia Coppola film starring Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson. It was both liberating and alienating for him to be in an unfamiliar place. Even while he was learning much from newfound Dutch friends and acquaintances, he also had many opportunities to share something with them. “We might be poor but not in spirit. Plus they were fascinated with the magic-realist-like landscape of Palawán storytelling.”

At the heart of Kanakan’s many films and stage plays is his soul’s true home, Palawan. His return to stage writing and directing in 2015 yielded another widely celebrated drama, Mga Buhay na Apoy (A Breath of Fire), which also won the coveted Don Carlos Palanca Memorial Award for a full-length play. It is his most personal work to date because it captures how the Palawán people assimilated into the culture and society of Manila.

While the Netherlands may have been the longest period he had stayed away from his home, Kanakan has traveled to other parts of the world, usually to represent the Philippines in one film festival or another. Of the many places he has already been to, it is to Havana, Cuba, where he would like to return and possibly live in for a few years, away from the hectic pace of creating.

“That is the only country where I really didn’t want to leave. It was fun, dancing every day. Everyone is intelligent (99.8 percent literacy!) and open. I hit it off with the Cubans. I share their temperament. There, I was my pure self. They would say, ‘Solito, you’re not Filipino; you are Cubano acting like a Filipino.’”

Kanakan may appear to be a citizen of the world, but he is first and foremost a Palawán, advocating for the various concerns threatening his people and home. He was a catalyst for the Ancestral Domain Claim of the Palawán in South Palawan by taking part in the formation of an indigenous organization called Sambilog, which means “oneness” in the Palawán language. He is aware that he owes Palawan much of his creative energy. When he is in the process of writing, directing, or designing, he cherishes his dalos beads over everything else. “They were given to me by shamans. They are beads with natural holes in them, found in flowing rivers in Palawan, as if nature made them for humans. They are used to ward off evil.”

In these troubled times, it is a breath of healing fire for the rest of humanity to have a creator like Kanakan mindful of fighting evil and being vigilant against it.

Agatha Verdadero runs the first and sole digital-only trade publishing house, The CAN-DO! Company, in Kenya and East Africa. She loves to travel, write, daydream, and play outdoors. She has enough scar stories now from cycling and trekking to write a book.

More articles from Agatha Verdadero