Mother Tributes: My Mother's Feminism

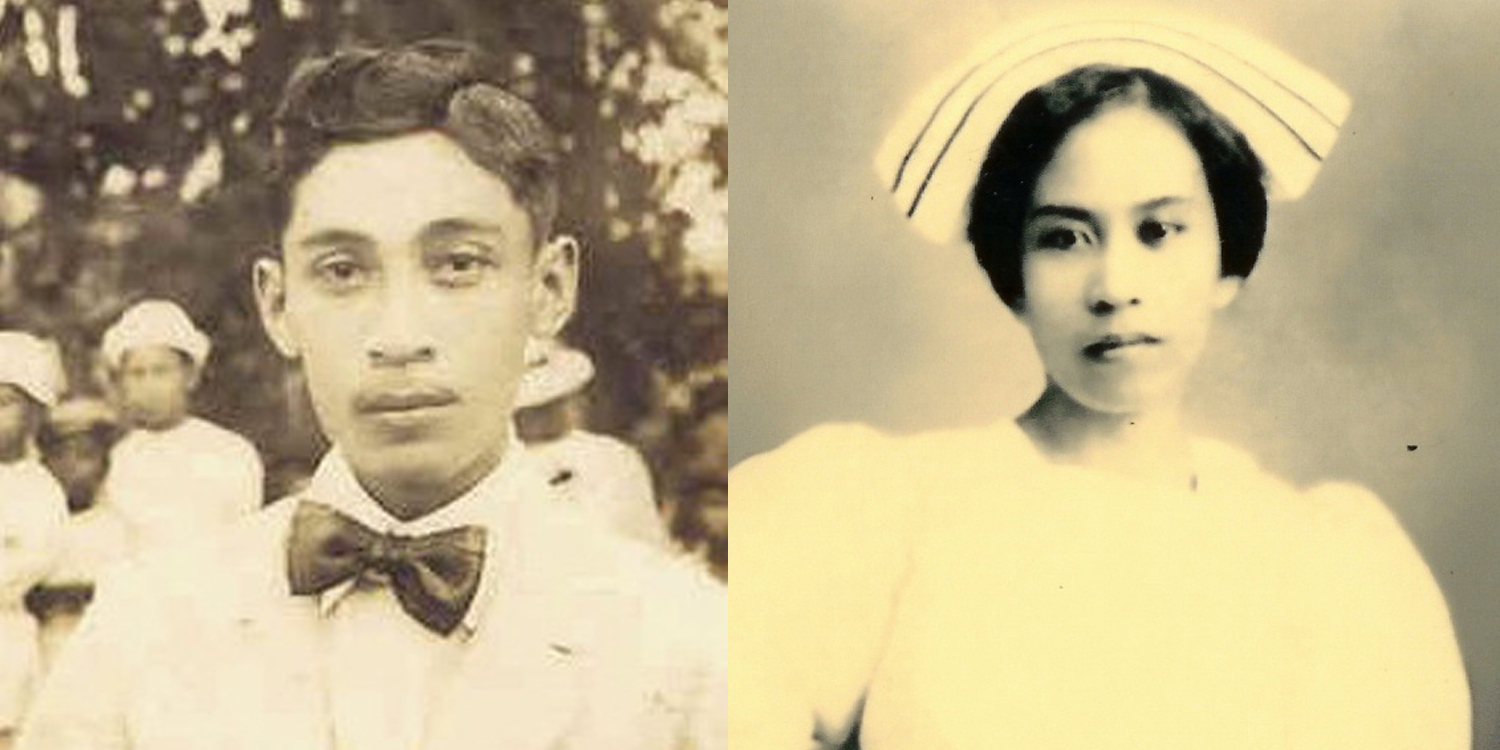

/Left: Modesto Aquino, San Fernando, La Union, early 1920s. Right: Teresa D. Ancheta as a nursing student at PGH, 1916 (Photos courtesy of Dr. Belinda Aquino)

She was my first "teacher" when I was three, using the headlines of The Manila Times for my "alphabet" lessons. I don't remember anything about that part of my childhood, but she said she was overjoyed when I said "A" as she pointed to the first letter A in the word Manila. And I said A again when she pointed at the second letter A in the same word. That meant I was going to be normal after all, allaying her fears. Then again she would ask me what I wanted to be when I grew up, and I would reportedly say, "Laolao lubong," in baby talk, meaning "go around the world."

Because all my older siblings were in school, my mother became my playmate and friend as well. She took me to the marketplace just about every day and leave me with her female cousins, who were vendors selling everything from vegetables to mosquito nets. I would fall asleep, my aunts said, on the pavement waiting for my mom to finish with the marketing, not only for our house, but also for many of our neighbors, who made bilin (requests) to her to buy them this and that. Looking back, I felt sorry for her because she never said no to those requests.

She was always the neighborhood's epitome of kindness, patience and generosity. Imagine having to do everything for a large family plus a number of relatives who would come from the barrio to live with us so they could go to school, plus the neighbors, and so on. Yet she never lost her cool. I was the one angry for her. She didn't have much disposable income as my father didn't earn that much as the town secretary for 23 years.

It became worse after he was elected mayor shortly before World War II, and more people and relatives came to the house. That would’ve brought further aggravation, but my mother took it all in good stride, not that she was a wimp; she was just a very kind soul. It was perhaps due to her deep spirituality, which I did not inherit, unfortunately. She went to church just about every morning and was the community leader in praying sessions.

“There are many kinds of “feminisms,” and our Filipino mothers and fathers exemplify many of these various forms that enrich and guide our lives.”

When I came of age, I had to leave the province and head for the "big city." My mother insisted on accompanying me to Diliman, Quezon City, where the University of the Philippines (UP) relocated after the war. It was, I think, for sentimental reasons because the UP she knew as a pioneer PGH nursing student from the Ilocos was on Padre Faura Street in Manila, which was devastated during the war. She felt like crying when she went back to the province after I had settled in a boarding house on campus. This separation from her “last-born,” as she often referred to me in Ilokano, for the first time must have been very painful for her. I knew then that I had to finish college right away, find a job and help out with her multifarious responsibilities.

After graduating from UP Diliman, I took a job right away in our province as a ghostwriter for our governor, who was looking for an “English major.” My mother—and in a sense my father, who was getting on in years--became the focus of my young adult life.

Because of our age differences, I wasn't that close to my siblings, especially my brothers who had their own barkada (clique) and were always out at the corner store, discussing politics and women. I had an early lesson in "feminism" because I bitterly complained about their not being around to help in the household chores. I also had the onerous duty of calling them from the streets when it was time to eat. Then they’d be gone again after eating to hang out some more with their barkada.

At times, during these "complaining" moments, my mom would say in Ilokano, "You have to be patient, anak (child), because this is our life." I didn't know what that was supposed to mean. My father would chime in and say, "You will make up for all of them." Again that would set me thinking: why should I "make up" for anyone's shortcomings? Later I realized that in our culture, boys will always be boys, but girls are expected to be and do better! The usual double standard which rankles in our minds.

Years later, when I was a graduate student in Cornell University in the ‘60s, I somehow understood that the Western concept of feminism based on gender equality was not the basis of my mother's and father's notion of a "woman's role" in the Filipino family.

A woman's "power" in our society revolves around a set of cultural values of patience, sacrifice, understanding and achievement in life. In many ways that kind of "power" is infinitely more meaningful than a one-to-one correspondence of the notion of equality between men and women.

There are many kinds of "feminisms," and our Filipino mothers and fathers exemplify many of these various forms that enrich and guide our lives.

Belinda A. Aquino is professor emeritus at the School of Pacific and Asian Studies, University of Hawaii at Manoa in Honolulu.