Paternal Instincts

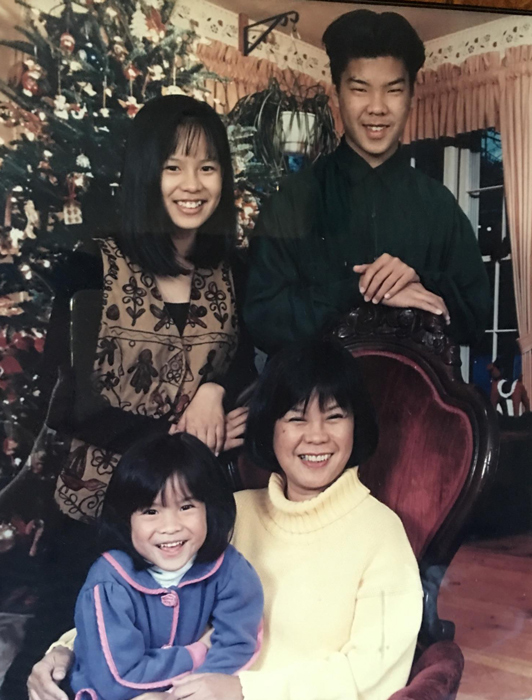

/The way we were 20 years ago (Photo courtesy of Gemma Nemenzo)

My cynicism eases up a bit though when it comes to Father’s Day, even if I mistakenly thought that it was another one of those newly created, money-baiting marketing schemes. (Did you know that the first public Father’s Day celebration was in 1909 and President Lyndon Johnson officially designated the third Sunday of June as such in 1966?) I think it’s cute to have a once-a-year special day for honoring fathers, especially in this day and age when it’s awfully difficult to be a dad – especially when you’re a mom.

Like all single parents, the demarcation line between being a father and being a mother has long ago disappeared for me. I have gotten so used to this duality that, try as I may, I can no longer imagine a different life, where parenting decisions are shared, areas of responsibilities are divided, and the joy of parenting is not tempered by exhaustion from having to be two persons at the same time. Just being able to get through a day without a major mishap was already reason to celebrate.

My older children’s teenage years were character builders, for them and for me. We loved and fought with equal ferocity, each of us unsure of how we should play our roles yet conscious of the need to assume multiple ones to keep the family ship on an even keel. I still feel guilty when I remember how my son, who was only 10 when his father and I separated, had to take on adult tasks, like mowing the lawn and taking care of his younger sisters, at a time when he should have been a carefree kid. Did I rob him and his sister of their childhoods because of my decision to break free?

The need to be a father assumed a bigger dimension when my older daughter started dating, and my son was going through the often painful search for identity. I was entering highly emotional and basically unfamiliar territory, something that drew out in me the lingering traumas of my own youth.

Having had a very conservative and emotionally distant father, I was a natural rebel against dating traditions and anything that smacked of authoritarianism. While a Filipino father would be strict and scary to the boys who hovered around his daughter and who wanted to take her out, I was torn between sternness and permissiveness, knowing full well how, as a teenage girl, I felt embarrassed when my father insisted that I not get into a car along with a boy. I remember how I longed to be trusted by my parents and I wanted to give my then-sixteen year old daughter my full trust.

Yet there was a part of me that reflected my parents’ anxiety: what if the boy wasn’t trustworthy? Should I have done what one Filipino father did before his daughter’s first date – took the boy out to dinner and read him the Riot Act?

Raising a son was an entirely different ballgame – I just didn’t know how! I pored over parenting books and asked my friends for whatever tips they could give. But ultimately, I realized that there were no instruction manuals, nothing to make me understand completely the growing pains that my son was going through. I went by my instincts and braced myself for the inevitable clashes, willing myself the strength to ignore the Mohawk haircuts, the ridiculous outfits, the sullen teenage face, the coming-home-at-dawn and sleeping-all-morning practices. I kept reminding myself to allow him these little rebellions as long as he didn’t end up in prison or rehab.

Then my son and daughter reached driving age. It was the one rite of passage that I considered a father’s domain but I had no choice but to preside over it – be the one to sit beside them barking instructions as they tentatively negotiated their way through the streets of our neighborhood, as well as the treacherous alleys of pre-adulthood. They were on their way to freedom while I was a nervous wreck, scared of the dangers they would face, and distressed at the prospect of loosening the parental heartstrings.

Some weeks ago, my three kids and I were together for a few days – a rare occasion now since my older daughter, who is 24, has been living on the other coast for years. My son is now 26, my youngest daughter 16. We are a family welded more tightly by the many burnings we had to go through.

It warmed my heart to see them, who were once my crosses, independently and determinedly forging their way toward their own chosen lives. And I give thanks for everything that we have been given. Everything, including the chance for me to be their mother and father at the same time.

From Heart In Two Places: An Immigrant’s Journey (Anvil Publishing Inc., 2007)