Out the Back Door

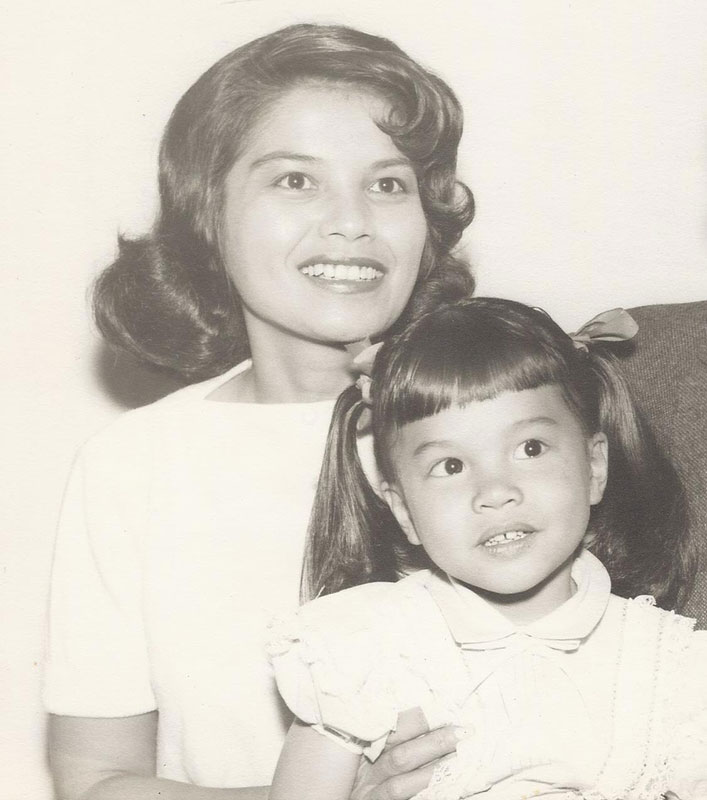

/Anita Alfafara Suguitan and the author (Photo courtesy of Lisa Suguitan-Melnick)

Feel the windy Geary Street traffic. It rustles up under your slip, blowing your dress like a billowed sail. The heavy air from the parlor sticks to your face. Feels like a maroon-colored velvet curtain pulling tightly around your nose and mouth, wrapping round and round the flat-nosed little girl in the dark green dress with a scalloped white collar. Curtain swaddles a skinny brown body down around chapped scabby knees. Balls of dust tumble from between the pleats, dropping down into your lace bobby socks. The dust balls are “pom-pom” bugs with a life of their own; now, the curtain tucks its excess length underneath your new Mary Jane shoes. Feeling smothery about the nose, you walk as if shackled at the ankles, shuffling on tippy toes behind Auntie Lucrecia in fainting steps. Unable to move your arms, unable to feel your body under the thick velvet curtain, you hope that you’re not really here at all.

Just moments before being led out the back door, low-voiced conversations among relatives who hadn’t seen each other for a while made you aware of each achy second that passed. An uncle shuffled by the front pew where you and your little brother sat, dabbing his oily forehead with a hankie as he made his way toward your mother’s casket. His walker landed three times on the fleur-de-lys carpeting. Tap. Sh-h-oop. Tap. Sh-h-oop. Tap. Sh-h-oop. Finally he arrived, leaning in close enough to gaze into your mother Anita’s face.

Oh, my goodness, ‘Nita. Only thirty-three years old, darling. Why did you hab to die so young? His wailing caused Grandma to come forward to join in.

What will the children do without their mother, honey dear? Look at them. So young! Ay nako. Grandma resumed wailing where she had begun four days earlier.

***

Right in the middle of the Girls section of Sears Roebuck, while shopping for funeral clothes for you, she had told every salesgirl, My granddaughter needs a dress. She is my granddaughter. For a funeral. Do you have black in her size? Da mother died.

Grandma managed to continue rambling through her sobs. Mmm-hmm. We need a black dress. A black sweater. For the funeral of her mother.

She grabbed for you, pumping your arm as if checking the ripeness of a mango. She accepted each sympathetic response from the salesgirls as an invitation to add more details.

She was very sick. In the hospital for over one week this time. She died. Last Thursday.

“Oh, my goodness, ‘Nita. Only thirty-three years old, darling. Why did you hab to die so young? His wailing caused Grandma to come forward to join in.”

Tactfully the salesgirls kept their eyes on your grandmother and off of you. Your stomach, holding a jagged pit the size of a fist, sent nauseating heat to your profoundly heavy chest. Grandma settled on a pine green dress with a white collar, black lace bobby socks, a gray coat, and a new pair of size 10 patent leather Mary Jane shoes.

From that day on, you would forever detest shopping.

***

Now sitting in the family section of the funeral parlor, separated from the people, you replayed that shopping scene while you looked down at your lap, noticing that the pine green dress had subtle triangular patterns in the fabric. You avoided looking at anyone in the funeral parlor by moving your eyes to a spot just above the casket. You focused hard on the lower left corner of the brushed silver crucifix of Jesus hanging against the rosewood backdrop. Two nights earlier, when you had first laid eyes on the grayish pallor of the face of this woman in the beautiful rose-colored casket, heavily made-up and fake-looking, you pitched backward, mind racing too fast for your body. You thought you were in the wrong parlor because that woman lying in the casket could not be your mother. Wait. Did your mother die, or is this simply a dreadful dream?

You remember seeing her facial expression as odd: lips pinched together a bit tight and turned slightly downward; edges of her eyes turning down the same way, like they were about to cry. Was she in pain at the end? No, her expression means she knew her life was to end, you decide.

Oh, no, I am not going to be able to see my precious kids. (To remind us to obey your dad.) Please bring the kids to see me one last time. (To tell you that Mommy is feeling all right now; but that she has to leave.)

Be tough girl. Strong Girl. Smart Girl. (To tell you to take good care of your little brother. To encourage you to do well in school.)

You’re a good big sister. (To kiss your cheeks, and whisper in your ear, Don’t worry. Mommy will always be near.)

Suspended there, you are the only person in the room, your eyeballs distracted by a movement overhead, where you find… yourself… fluttering on wings above your own body, hovering above the impending last night of your mommy’s Rosary -- the Rosary of this woman in the pink casket. Close your eyes. If you sing to yourself, will you open your eyes and be someplace else, any place else but here?

Three six nine, the goose drank wine

The monkey chewed tobacco on the streetcar line

The line broke, the monkey got choked

And they all went to Heaven on a little green boat.*

C’mon, let’s go out. Dad’s sister, your Auntie Lucrecia, holds tight to your hand as she turns you toward her, dabs at your tears, guides you out the back door of the east parlor onto Geary Street, and buttons up that ugly gray poodle coat against the damp December air.

Lisa Suguitan Melnick is a professor at College of San Mateo, teaching in both the Language Arts and Kinesiology divisions. In the 2014 Plaridel Awards she earned honorable mention in two categories: Best Investigative/In Depth Story, “Celestino’s Crusades” and Best Personal Essay, “Just Because.”

More articles by Lisa Suguitan Melnick:

Eat All You Can

November 6, 2012

First-time visitor Lisa Suguitan Melnick discovers the quirks of Filipino life.

Vangie Looks Back

February 6, 2013

Vangie Canonizado Buell, descendant of a Buffalo Soldier who was stationed in the Philippines, is a beloved figure in the San Francisco Bay Area Filipino American community.

Book Review: A Big Hearted Book On Little Manila

September 11, 2013

Author Dawn Mabalon digs up the past and brings Stockton, California’s pioneer Filipino community back to life.

Celestino’s Crusades

October 17, 2013

Filipinos who own property in California owe a lot to pioneer Celestino T. Alfafara.

Just Because

November 2, 2013

A first-time visitor to Manila, the grandniece of a late missionary nun, navigates its traffic maze to find the missing piece that will fill the longing in her heart.

Rosa Linda Who-Loves–Her-Job

October 13, 2014

In Cebu, the author finds the key to a surly Ice Castle Restaurant server’s heart.

Maség, An Artistic Tempest

February 1, 2015

Three creative minds get together to spin a fierce, sensual tale with music and dance.