Fermin Tobera: From Historical Footnote to the Big Picture

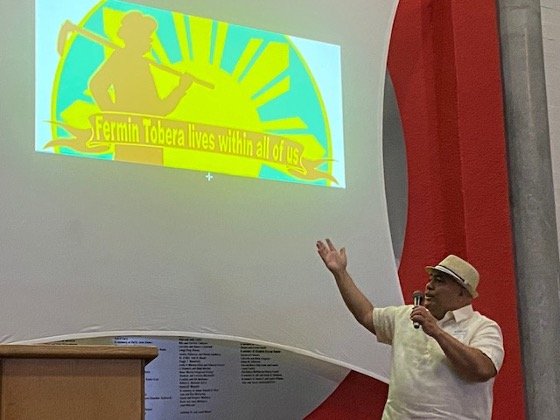

/Roy Recio Jr. unveiling the Fermin Tobera mural project (Photo courtesy of Roy Recio Jr.)

UC Santa Cruz Professors Steve McKay and Kathleen Cruz Gutierrez (on stage) introduce the “Watsonville Is in the Heart” digital community archive to a packed audience at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History last April 9 (Photo courtesy of Roy Recio Jr.)

Now, the Tobera Project has scored a milestone in its campaign to elevate Fermin Tobera from a mere footnote in history to literally, a painting on the wall.

The Project will install a mural paean to Filipino farm workers with the focal figure of Fermin Tobera set along other murals depicting other immigrant groups who struggled to make Pajaro Valley what it is today.

Graphic designed by Ted Visaya (Courtesy of Roy Recio Jr,)

In Tobera’s time, when manongs turned out for fun after a week-long labor on the farm, they looked sharp in their rented or borrowed Mackintosh suits and flashy accessories. The mostly single manongs lacked for female companionship, but California law at the time forbade marriage between Filipinos and whites.

Trouble was brewing, and it was about to explode. When the Chinese were excluded, Filipinos became the primary source of cheap labor on the farms. The laws excluded Asians, but the Philippines was a U.S. protectorate. Filipinos were technically American nationals and they worked for less pay.

When the Great Depression began in 1929, Filipino farm workers were an easy target. As early as 1928, an anti-Filipino riot in Exeter, San Joaquin Valley erupted. What sparked it was Filipinos dating white women.

Courtesy of the UC Berkely Bancroft Library Archives

The Watsonville race riots is not even on the Top 10 list of race riots in the U.S. So much has been written about them especially by Filipino writers, but not a lot about Fermin Tobera.

Tobera Project founder Dioscoro Roy Recio Jr. took this to heart. He found purpose and cause in Fermin Tobera, a victim in a riot where the guilty never faced justice. But to some avid historians, the seemingly insignificant farm worker’s death became the cause celebre for Philippine independence from the U.S.A.

When Recio Jr.’s mother died in March 2018, he “felt that I needed to do something to honor my parents.”

Dioscoro Recio Sr. on Main Street in downtown Watsonville when he arrived in 1929. Missionaries invited him to come to America from Banga, Aklan after his first wife died, leaving him two daughters to raise. (Photo courtesy of Roy Recio Jr.)

Roy Recio Jr. and daughter Corinne Palma Recio with a photo of grandpa Dioscoro Recio Sr. (Photo courtesy of Roy Recio Jr.)

He brought together descendants from the manong generation who felt the way he did. “We just want to recognize Fermin Tobera because no other Filipino group is doing it. Larry’s (Itliong of the Delano grape strike in 1967 with Cesar Chavez) history is Larry’s. Issues in Delano did not always impact Watsonville. Since Fermin is from Watsonville his circumstance is a direct link to our community.”

He explained that Watsonville has a smaller Filipino community than Stockton or Delano. When they were young, the story of Tobera was often told. He grew up with Tobera not just as a cautionary tale, but also as a guiding light: “The race riot experience lives within our community and its descendants. We feel his ghost. This is why it is important to remember him. The dominant community in power/landowners/growers and the like do not want his story to be projected.”

A veteran community leader Recio Jr. was on the Manilatown (site of the forced eviction of poor Filipino elderlies from I-Hotel or International Hotel in 1977) board of directors with Rob Bonta. He also got involved with labor union leader Fred Basconcillo and was a founding member of the San Francisco Veteran’s Equity Center.

He recently wrote for the Filipino American National History Society (FANHS) that “Our history and stories are not accepted as important or true if they are not validated and institutionalized in the ivory tower. This is our way of honoring and dignifying our ancestors. It’s a dream come true for many of us.”

In May, the Tobera Project surpassed its $25,000 goal to be included in Watsonville Brillante, a community effort recognizing all the ethnic groups who made the fertile Pajaro Valley into what it is now. The 12,500-sq. ft. of mosaic tiles adorning 275 Main Steet, Civic Parking Garage in downtown Watsonville were re-purposed to depict the many cultures that migrated to the town, celebrating them in murals on 185 panels of the Garage.

Tobera Project’s depiction of Fermin Tobera will be a 4 ft. by 8 ft. mural with the central figure of a farm worker silhouette with a hoe slung over his shoulder surrounded by images of the lives of manongs in Pajaro Valley. Installation begins in the fall.

Their images will be immortalized among the likes of the Mayan Warrior strawberry picker and the Universal Man apple-picker.

The Project contracted Amor Aggari as a graphic designer. Aggari also designed the Tobera Project logo and website. He is brother-in-law to Emil De Guzman, leader of the tenants when they were forcibly evicted from I-Hotel.

In November 2020, the Watsonville City Council formally apologized for the residents’ actions against Filipinos in the 1920s and 1930s.

Although Recio Jr. said this was a step in the right direction, he stated in the Project newsletter, “It’s a slap in the face to us that we don’t have a street, school, building, or park bench named for one of us. Hopefully, this will get the ball rolling by city leaders.”

Aside from the successful fundraising and colorful calendars, the Project partnered with UC Santa Cruz to launch a digital archive in April. “Watsonville Is in the Heart” packed the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History in downtown Santa Cruz.

The archive collects paraphernalia of Filipino trans-Pacific migration, agricultural life in Pajaro Valley, and racist experiences in the early 20th century. Displaying arts, oral history, photos, albums, and personal letters, it is a bittersweet throwback to a time in history when Filipinos were Americans but did not belong in America.

The author wishes to acknowledge Mr. Bill Beecher and the Pajaro Valley Historical Association for their Watsonville Race Riots compendium.

Harvey Barkin is a reporter for San Benito County news portal BenitoLink. He was editor-in-chief at FilAm Star in San Francisco and freelance reporter for the San Jose Mercury News. He is also a reporting fellow for campaigns and grant-funded projects. Previously, he was a tech writer for Silicon Valley start-ups and a book reviewer for Small Press in Rhode Island. His work has appeared in different media from advertising copy and collateral to B2B content and in various outlets from Valley Catholic to Inside Kungfu.

More articles from Harvey I. Barkin